In recent years, academic coaching has become an increasingly popular resource for students in higher education. Unlike more established student support services on college campuses such as tutoring or academic advising, there is not yet a widely accepted model for practicing academic coaching (Robinson, 2015). In this article, we aim to move forward academic coaching by framing it in terms of design thinking. Design thinking is a collaborative solution generation process often used by large, private sector companies, such as Airbnb, Netflix, and UberEats (Han, 2022). In this article, we describe the practice of academic coaching, and describe how coaching fits within the self-regulated learning (SRL) theoretical framework. Next, we describe the design thinking process and highlight parallels between design thinking and academic coaching. Finally, we suggest ways to integrate design thinking procedures and SRL theory into the practice of academic coaching. Throughout this article, we share ideas for higher education professionals to use design thinking in their work with students and colleagues.

Academic Coaching

College students often face challenges as they work to meet the demands of higher education. Academic coaches are uniquely positioned to support college students as they navigate new learning environments and expectations (Alzen et al., 2021). Academic coaching is a support service that focuses on developing students’ self-understanding, goal-setting skills, academic and personal effectiveness, and persistence (Robinson, 2015; Sepulveda, 2020). Topics discussed in coaching sessions include effective study methods, time management, maintaining motivation, reducing procrastination, test-taking skills, and managing stress and anxiety to enhance well-being.

Although academic coaching programs vary widely across institutions, there are also common features of all academic coaching services (Sepulveda, 2020). Academic coaching is structured as a collaborative and personalized relationship between a student and their coach. The role of the coach is to provide emotional support through active listening and empathizing, to ask powerful questions to increase self-awareness, and to challenge students to set action plans for behavioral change (Robinson, 2015). Coaches can be faculty, staff, or students, and coaching can be incorporated into other types of interactions (e.g., academic advising). Coaching sessions are student-led, with the student directing the topics of conversation. A central tenet of academic coaching is that students are the experts in their own lives (National Academic Advising Association, 2017). The coach brings expertise in learning and motivation strategies to the relationship but must remain curious and open-minded to the students’ unique lived experiences. The coach functions as a mirror to help the student reflect and examine their own experiences and as a champion of the student to encourage positive growth.

Self-Regulated Learning

Although academic coaching is an increasingly popular service offered at institutions of higher education, it is a practice that has not been derived from theoretical models (Robinson, 2015). Academic coaching uses a metacognitive approach to building students’ motivation for learning along with improving their academic skills (Alzen et al., 2021), thus it can be situated within the self-regulated learning (SRL) framework (Howlett et al., 2021).

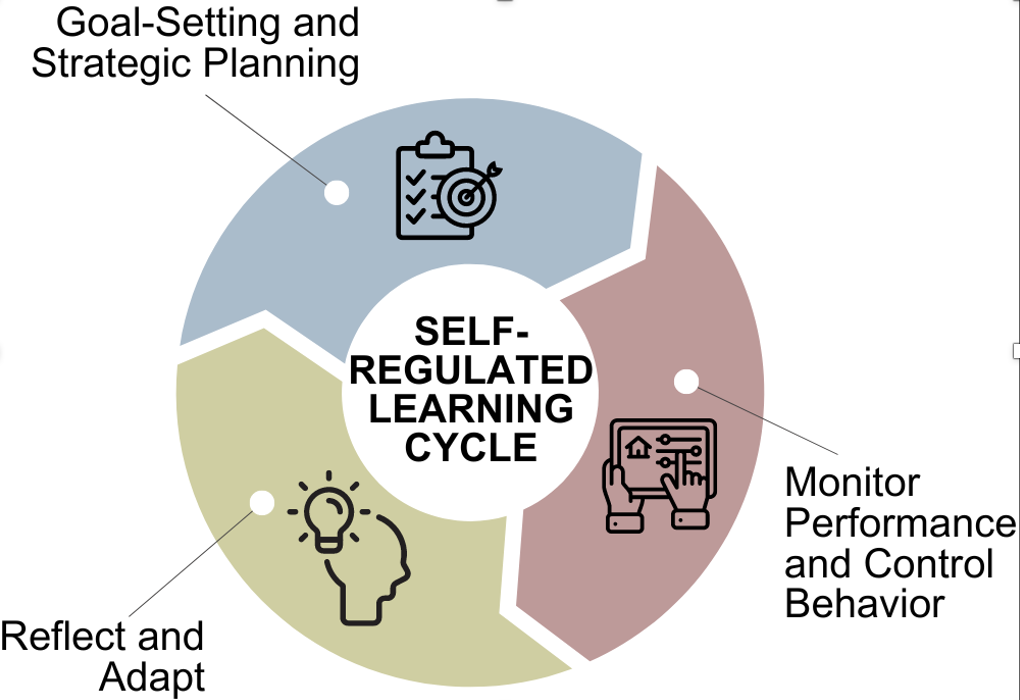

SRL is a self-directed process of actively engaging with one’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and behaviors to achieve academic or learning goals (Dent & Koenka, 2016). Although many models of SRL have been proposed (Panadero, 2017), there is agreement about the basic description of self-regulated learners as students who set learning goals and actively choose strategies that will allow them to reach their goals (Dent & Koenka, 2016). Self-regulated learners are also flexible and resilient, as they continuously adapt and adjust their plans, efforts, and strategies to be more effective. In the SRL framework, learners engage in a three-phase cycle while learning: preparing to complete the task (planning and goal-setting), working on the task (monitoring and controlling learning through strategy use), and evaluating the process after the task is finished (reflecting and adapting strategies and goals) (Zimmerman, 2000). These phases form a recursive cycle as each phase informs the next (Pintrich & Zusho, 2007). After completion of an academic task, self-regulated learners reflect on the experience and use this knowledge to adjust strategies and efforts for their next attempt.

Academic coaches support students through each phase of the SRL process. Coaches encourage setting appropriate and achievable goals, suggest active learning strategies, and ask questions of students to prompt reflection on their learning.

Figure 1.

Note. Created by author, adapted from Zimmerman (2000).

Design Thinking

Design thinking is a solution generation process, often used by private sector companies, to create useful and impactful innovations for change (Han, 2022). The design thinking process maps out an innovator’s workflow into five steps that place the human, or user, at the center of solution generation. Design thinking is solution based and user-centric, so it focuses on how to solve a problem, instead of the problem itself (Han, 2022). For example, in the context of higher education, an academic coach (the innovator) might meet with a student (the user) about their poor grades due to frequently skipping classes. The design thinking methodology would ask the student questions to get to the real reason why the student chooses not to attend classes and brainstorm ways to help the student attend classes and be successful in their learning.

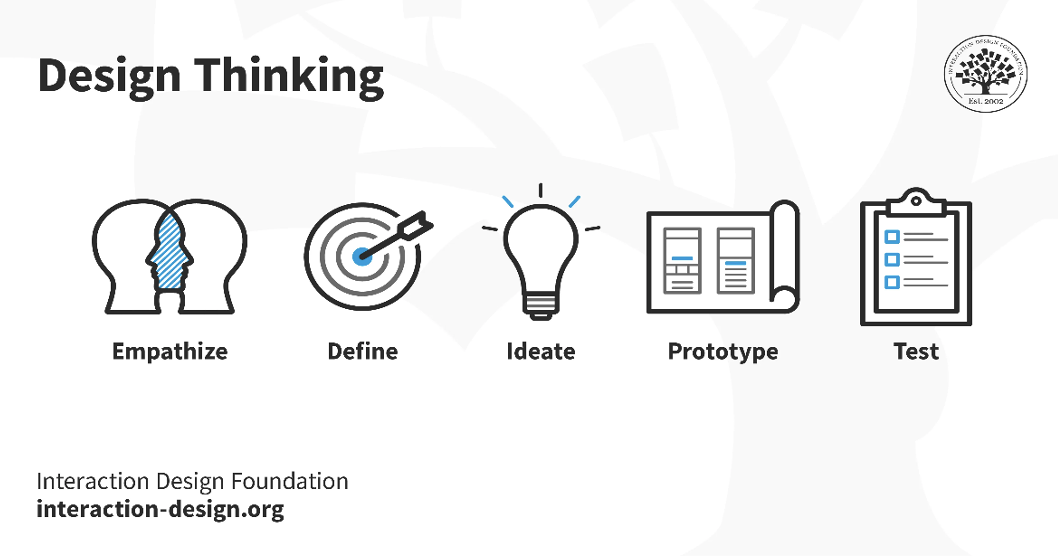

Figure 2.

Note. From Design Thinking Process [Screenshot], by Interaction Design Foundation, 2023, (https://public-images.interaction-design.org/literature/articles/materials/PONMo61b9QMX0GZvguvRft35nhDu3KG6Asa2NkI3.jpg)

The design thinking process is broken down into five steps – empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test (Interaction Design Foundation, 2023). The five-step process is outlined below, from the innovator’s perspective:

Empathize

Because the design thinking process brings users to the forefront of solution generation, it is important for an innovator to empathize with the user to understand the problem from their perspective and find a solution. This is often done through motivational or empathy interviews with the user. In this step, it is important for the innovator to set aside assumptions and ask questions of the user to gain insight into the real issue at hand.

Define

After empathizing with the user, the next step is to use the information gained through motivational interviews and define the problem. As the innovator analyzes their observations, they can then create a problem statement that will guide their ideation. The problem statement should combine the user, the user’s needs, and the insight the innovator gained–“[USER] needs to [USER’s NEED] because [INSIGHT] (Interaction Design Foundation, 2023).

Ideate

After the innovator defines the problem, the next step is to generate ideas for potential solutions. It is important to note that in this step, the innovator is not choosing a solution. Instead, the role of the innovator (in collaboration with the user) is to brainstorm all possible solutions. This is the time to be creative and nonjudgmental–all ideas are worth considering at this stage.

Prototype

Next, the innovator will evaluate their ideas and identify the best solution to the problem. This is the time to think about what is most beneficial and realistic, considering both the user’s perspective and the innovator’s expertise.

Test

Finally, after empathizing, defining, ideating, and prototyping, the innovator and user will test the solution and evaluate the results. Although this is the last step in the process, design thinking is iterative. Innovators are encouraged to use what they learn from testing and alter or refine the solution to best fit the user’s needs.

There are a few important things to understand about design thinking before applying it to academic coaching. Design thinking offers a defined procedure for innovation (Han, 2022), but the steps contribute to the entire solution process and do not necessarily have to be sequential. The focus of design thinking is to understand the user and what their ideal solution would be. Thus, it is important to engage in design thinking as a collaborative process.

Applying Design Thinking to Academic Coaching and SRL

Design thinking is a practical procedure that can enhance established theoretical frameworks used in academic coaching. Understanding the steps of the design thinking process and putting the student first allows coaches to build a collaborative relationship with the student from the beginning. A SRL approach to academic coaching requires students to be an active participant in their learning, similar to how design thinking centers users in its model (Howlett et al., 2021). Combining the two models allows coaches to prepare students for academic and future success.

As we described, SRL is a cyclical model that has three phases–planning and goal setting, monitoring, and controlling, and reflecting. SRL is a useful tool that allows students to sustainprogress toward a learning goal (Howlett et al., 2021). It is a validated theoretical framework for academic coaching but lacks clear operating instructions on how to guide students through the process. Design thinking can help.

While design thinking is iterative, the first step is often empathy. Empathy can be applied to the reflection stage of SRL in an academic coaching scenario. Asking motivational interviewing questions to guide the student to reflect on what the core issue is or what solution they are seeking is a helpful way to start a coaching session. Some potential questions academic coaches can ask:

- What brings you to coaching?

- Where are you feeling frustrated in your academics?

- Think of a time when you were academically successful–what worked well?

The next steps in design thinking are defining the problem and ideating solutions, which together correspond to the planning stage of SRL framework. After empathizing with a student through reflection, academic coaches can define the problem to help both the coach and the student articulate their concerns and begin to plan for a solution. Empathy remains present throughout this stage because it is important to make sure the solutions generated are strategies that could potentially work for the student. Further, empathy is integral to maintaining the collaborative nature of design thinking and the self-direction of SRL. Once the academic coach and student have generated three to four potential solutions or strategies, they can proceed to the next step of the process. To ideate solutions, an academic coach may ask:

- In an ideal world, how would this work for you? What would you like to happen?

- Have you tried this strategy before? If so, what worked and what didn’t work?

- What other strategies have you heard of, but not tried before?

- How could you adjust this strategy to make it work for you?

The final design thinking steps–prototyping and testing–are analogous to the monitoring and controlling phase in the SRL framework. Once a student decides which strategies they are going to try in their learning, it is time for them to test it. This involves mostly SRL ideals in that the academic coach may not be with the student when they are testing out a new strategy (e.g., while studying for an exam); however, the academic coach can provide the student with tools to monitor how they feel when trying a new strategy or to control their emotions while trying a solution. For example, an academic coach may suggest that a student takes breaks while studying for an exam to check in with their understanding and to remind themselves of the value of what they are studying.

- What can you do today/this week to make these changes?

- Is this plan realistic?

- What might be an obstacle when you try this? What might go wrong?

As an iterative process, it is essential that the process does not end here, but instead cycles back to empathy. In both design thinking and SRL, reflection is an important behavior to engage in after testing a solution to a problem. In academic coaching, the coach can check in on the student or encourage the student to reflect on their experience on their own. The coach may ask:

- What went well?

- What did not go well?

- What would you do differently in the future?

Asking these questions is an important part of finding out what works for the individual student and maintaining their motivation toward behavior change. As aforementioned, setting assumptions aside is a key element of design thinking and should be applied to SRL and academic coaching as well. As coaches, we cannot assume what worked for one student will work in the same way for another. Empathizing throughout the coaching process allows both the coach and the student to feel engaged and valued in the process.

Applying Design Thinking to Academic Coaching Scenario

Coach: What brings you to academic coaching? Where are you feeling frustrated in your work?

Student: I have a hard time focusing on my assignments, especially when the assignments involve writing.

Coach: Can you think about a time when you successfully wrote an assignment? What worked?

Student: I feel like I have only been successful when the assignments are short. I can’t focus when they are too long. I get distracted easily.

Coach: Okay. What I am hearing is that you are frustrated when you can’t complete long assignments due to distractions. Let’s brainstorm some ideas to limit distractions and increase your concentration. Do you think you could break the assignment into smaller chunks? Or maybe find a new space with less distractions to complete assignments?

Student: I am always cramming to complete assignments, so I never have time to break them into smaller pieces, but I like that idea. I want to try that and make a plan to complete the assignment over more time.

Coach: That might help you get less distracted, as well.

Student: I agree. I look forward to testing it out and look forward to our follow-up meeting to debrief!

What makes this approach different?

Many coaching models are based on how the coach should interact with the student (e.g., GROW model), but not how the student can interact with the coach and feel that it is a collaborative session (Whitmore, 2009). Design thinking is a process that is well-established outside of higher education and can be easily mapped onto the SRL theoretical framework, demonstrating the legitimacy of the academic coaching process to students who may be hesitant to engage. Design thinking offers academic coaches the chance to collaborate with students and bring them into the solution generation process, maintaining the student-led nature of coaching. Additionally, using design thinking in the coaching process makes empathy explicit. While we can assume that academic coaches will approach their sessions with empathy, the design thinking process makes empathy an explicit part of the approach, putting students at the center of the solution generation. By putting the student at the center, there is potential for more buy-in from the student. Moreover, design thinking is focused on the solution to the problem, not the problem itself. This is an asset-based approach to coaching that allows the students to think about the changes they can make to be successful instead of focusing on what is holding them back.

Design thinking offers a step-by-step process that coaches and students can easily comprehend and apply in their work together. Finally, applying design thinking to academic coaching allows for solutions to be student-centric and provide personalized support.

Implications for Practice in Coaching and Beyond

In this article, we outlined how to apply design thinking to academic coaching; however, design thinking offers a framework to enhance many models or practices in higher education. We offer implications for practice below.

Academic Coaches

- Training: We encourage you to think about ways you can incorporate design thinking into your coach training process. Teach your coaches the design thinking procedure and make each step of the process clear. You could also use design thinking to help explain academic coaching to stakeholders or on academic coaching websites.

- Research and Evaluation: As practitioner-scholars, we have plans to investigate the effectiveness of applying design thinking to academic coaching. We expect design thinking to improve students’ understanding of academic coaching generally and improve their experience in academic coaching sessions, and we encourage additional research and evaluation on this topic.

Administrators or Managers

- Individual Team Problems: Your role may not be student-facing, but we encourage you to bring elements of design thinking back to your team or office, as it could be useful in solving day-to-day issues or larger problems your team is facing. You could use elements of design thinking as an approach to individual employee coaching or team meetings.

- Campus Issues: Maybe you are noticing a trend on your campus or students are asking for solutions to a problem they are facing. Design thinking offers the opportunity to bring students into the fold. Really think about who your user is and provide space for them to bring their perspective into the solution generation process. So often, decisions are made at the top when they affect those on the ground. Using a collaborative approach, like design thinking, might allow for more sustainable solutions in the long run.

Student-Facing Roles

- Student Interactions: Although we applied design thinking to academic coaching, we encourage you to use elements of design thinking in whichever facet of student affairs you may sit. Design thinking can enhance your interaction with students by allowing time to empathize and include the student in the solution generation process.

- Set Assumptions Aside: It is so easy to get stuck in the “one-size fits all” mindset, especially if your job entails back-to-back student appointments, all wanting to talk about the same thing. Yet, it is important to set your assumptions aside and listen to the student and their needs. For example, in academic coaching, we often meet with students about time management. If we provided a quick fix, one-size fits all solution to each student wanting to improve their time management, it would not be applicable or relevant for most students. Pulling from design thinking, we encourage you to start with empathy to really understand what each individual student needs.

- Clear Instructions: Change may happen slowly in higher education, but we know that daily tasks move fast. Design thinking’s step-by-step procedure can give practitioners time to ground themselves in the situation by working through the process. With students, it allows them time to slow down and really understand the solution they are seeking.

- Use What You Need: As student affairs practitioners, we understand that it is sometimes hard to take the time to work through problems and find “the best” solution. While design thinking offers clear instructions on how to approach problem-solving, you do not need to use every part of the procedure. Take what you need for the situation at hand. Maybe you only have enough time to define the problem with a student. Use that time to empathize through motivational interviewing and then define the problem together. The beauty of design thinking is that it provides individualized support, scaffolded by a clear process.

Reflection Questions

- Who are your users (students, families, faculty, alumni, etc.)? What are the problems that your users are sharing with you?

- How can design thinking increase students’ buy-in to make behavior changes?

- How can design thinking complement the frameworks you currently use?

References

Alzen, J. L., Burkhardt, A., Diaz-Bilello, E., Elder, E., Sepulveda, A., Blankenheim, A., & Board, L. (2021). Academic coaching and its relationship to student performance, retention, and credit completion. Innovative Higher Education, 46, 539-563.

Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Han, E. (2022). 5 examples of design thinking in business. Harvard Business School Online. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/design-thinking-examples

Han, E. (2022). What is design thinking and why is it important? Harvard Business School Online. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-design-thinking

Howlett, M. A., McWilliams, M. A., Rademacher, K., O’Neill, J. C., Maitland, T. L., Abels, K., Demetriou, C., & Panter, A. T. (2021). Investigating the effects of academic coaching on college students’ metacognition. Innovative Higher Education, 46, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09533-7

Interaction Design Foundation. (2023). Design thinking. Interaction-design.org. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/design-thinking#:~:text=Design%20thinking%20is%20a%20non,are%20ill%2Ddefined%20or%20unknown.

Interaction Design Foundation. (2023). Design thinking process [Screenshot]. Interaction-design.org. https://public-images.interaction-design.org/literature/articles/materials/PONMo61b9QMX0GZvguvRft35nhDu3KG6Asa2NkI3.jpg

Interaction Design Foundation. (2023). Problem statements. Interaction-design.org. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/problem-statements

National Academic Advising Association (2017). Academic Coaching Advising Community. Retrieved from https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Community/Advising-Communities/Academic-Coaching.aspx

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(APR), 1–28.

Pintrich, P. R., & Zusho, A. (2007). Student motivation and self-regulated learning in the college classroom. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based practice (pp. 731–810). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0245-5_2

Robinson, C. E. (2015). Academic/success coaching: A description of an emerging field in higher education. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Carolina-Columbia. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3148.

Sepulveda, A. (2020). Coaching college students to thrive: Exploring coaching practices in higher education. Doctoral dissertation, University of Northern Colorado. Retrieved from https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1690&context=dissertations.

Whitmore, J. (2009). Coaching for Performance, GROWing Human Potential and Purpose, The Principles and Practise of Coaching and Leadership, 4th Ed. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attainment of self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Author Biographies

Jackie von Spiegel (she/her): Jackie von Spiegel is the Program Manager for the Dennis Learning Center at The Ohio State University. In this role, she manages the university’s academic coaching program, which focuses on developing students’ learning and motivation strategies. She received an M.A. in Developmental Psychology and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Educational Psychology at Ohio State. Her research focuses on college students’ academic help-seeking. Jackie previously served as a Senior Academic Advisor and Lecturer in the Department of Psychology.

Sydney Rubin (she/her): Sydney recently earned her M.A.in Higher Education and Student Affairs from The Ohio State University, making Sydney a double Buckeye having received her B.A. from the John Glenn College in 2018. She values applying theory to practice to enhance the student experience. Sydney has previously served as a Program Coordinator, Academic Coach, and Assistant Hall Director.