written by: Zayd Abukar, Ed.D.

Introduction to the Study

Collegiate honors programs provide high-ability students rigorous academic experiences and increased access to co-curricular opportunities compared to traditional paths of study. Despite their numerous academic and social benefits to student success, honors programs typically lack student diversity, enrolling lower proportions of underrepresented minority (URM), first-generation college students (FGCS), and low-income college students relative to their general institutional populations (Brimeyer et al., 2014; Cognard-Black & Spisak, 2019; Rinn & Plucker, 2019). As collegegoers increasingly belong to one or more of these groups, campus leaders must consider how they can create conditions that better promote their achievement in honors.

In 2021, I conducted an independent dissertation in practice study examining FGCS retention in the honors program of a large public research institution in the Midwest. The goal was to help the research site begin to understand these students’ experiences with constructs researchers associate with retention. This was done as part of the research site’s broader effort to ameliorate FGCS’ and other populations’ disproportionate underrepresentation in the honors program relative to their enrollment across the institution. This article presents a concise overview of my research and its implications for practice.

Study Objective

This exploratory study examined factors associated with program retention of FGCS via the central research question of “what retention factor differences exist between retained FGCS and retained continuing-generation college students (CGCS) in the [research site’s] honors program?” CGCS were used as the comparison group from whom I drew broader insights about the primary population of interest.

Numerous research studies established that FGCS are more likely than CGCS to experience challenges that impede their retention and success in cocurricular programs and college altogether (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2018; Strayhorn, 2006; Terenzini et al., 1996). In contrast to the deficit-based lens often applied to studying this population, I elected to use an asset-based approach by studying a successful subset of FGCS: those who have persisted in this institution’s honors program. Identifying the forces that helped or hindered FGCS who have successfully navigated this academically demanding environment, where their marginalized social identities were magnified, not only challenged traditional narratives around their experiences, but yielded critical insight for the leaders tasked with supporting them through policies, practices, procedures, and programming.

Definitions

This study adopted the federal government’s definition of FGCS: neither parent has completed a bachelor’s degree (NCES, 2018). A CGCS is regarded as a student with at least one parent who has earned a bachelor’s degree (NCES, 2018).

Retention in the context of this study primarily refers to a student’s on-going participation in the honors program during their third year of college or beyond. This distinction was decided in consultation with the research site, as this point in a student’s honors career marks the threshold by which they will have achieved several key programmatic milestones that indicate a high likelihood of program completion and honors graduation.

Relevant Literature

How Honors Programs Impact Students

Honors programs are powerful student success vehicles (Bowman & Culver, 2018; Brimeyer et al., 2014; Cognard-Black & Spisak, 2019; Cuevas et al., 2017; Miller & Dumford, 2018). They positively influence students’ academic measures, such as GPA (Bowman & Culver, 2018), as well as affective measures, such as self-concept (Plominski & Burns, 2018). From a social integration perspective, honors programs cultivate robust student–faculty and student–peer interactions throughout the student’s career—a benefit non-honors students do not realize to the same extent (Cuevas et al., 2017; Jarzombek et al., 2017; Wawrzynski et al., 2012).

Honors Impact and Retention are Relative to Certain Conditions

Despite several advantages to honors programs, students benefit from pursuing an honors pathway only so much as it aligns with the student’s goals (Miller & Dumford, 2018). For one, it is not the fastest route to degree completion. This renders honors programs less appealing to students aspiring to graduate as soon as possible, or to those who cannot afford a longer time to degree.

In addition to goals, program characteristics—such as cocurricular experiences, networking opportunities, and quality of academic advising—also influence whether a student decides they will continue in honors (Kampfe et al., 2016). Some academic majors have more intensive honors requirements than others (Savage et al., 2014), suggesting the challenge of pursuing an honors pathway is not equally felt by all students, which may have implications for honors student persistence.

Lastly, some students simply struggle with the heightened demands of an honors curriculum (Cuevas et al., 2017). First-year honors students tend to overestimate their academic skills upon entering college (Clark et al., 2018). Mid-program check-ins or regular advising meetings can support honors persistence (Clark et al., 2018), but depending on program practices, these engagements may not occur.

Barriers to Honors FGCS Retention and Success

The Academic Adjustment to Honors Can be Challenging

The academic adjustment to college is a frequently cited challenge for FGCS. Decades of research present FGCS as more likely to academically struggle than their (CGCS) counterparts (Strayhorn, 2006; Terenzini et al., 1996; Vuong et al., 2010). However, simultaneously, honors students tend to be academically high performing (Miller & Dumford, 2018). The inference is that preparation and ability are less likely to be the primary causes of academic obstacles faced by FGCS in honors programs.

Pedagogical practices that value lived experiences, encourage classroom community, or provide explicit tools for navigating academia have been associated with FGCS academic success (Ives & Castillo-Montoya, 2020). As noted earlier, some honors majors are simply more demanding (Savage et al., 2014). Moreover, some majors tend to produce competitive environments, which have been shown to hinder FGCS’ learning (Canning et al., 2020). These realities indicate environmental and structural factors should be considered when assessing FGCS’ academic outcomes. Individual-level factors unrelated to ability or preparation weigh on this population as well. Stress (Garriott & Nisle, 2017; House et al., 2020), pressure (Rinn & Plucker, 2019), low self-efficacy (Elliott, 2014; Vuong et al., 2010), and over-self-dependence (Chang et al., 2020) are prevalent among FGCS, and especially in honors environments.

Issues Related to Finance Can Hinder Honors Engagement

FGCS are more likely to come from lower-income families, and more likely to have to work during college (Adams & McBrayer, 2020; Havlik et al., 2020; House et al., 2020). Working during college can afford FGCS opportunities to foster human, social, and cultural capital they otherwise may not be able to (Núñez & Sansone, 2016; Salisbury et al., 2012). For these benefits to be realized, however, work obligations must be flexible, meaningful, and accommodating to the other demands the student may have (Núñez & Sansone, 2016), such as participating in an honors program. Unfortunately, not all FGCS who work during college have jobs that meet these criteria. Work obligations restrict the extent to which FGCS can engage with honors services or develop meaningful relationships with honors peers (Garriott et al., 2017; Gibbons et al., 2019; House et al., 2020; Stebleton & Soria, 2013).

The Honors Climate Can Be Unwelcoming for FGCS

FGCS can develop feelings of not belonging or being subordinate to peers as early as when they first matriculate to campus (Havlik et al., 2020). These feelings are compounded by the subtle instances of discrimination FGCS often face, also known as “microaggressions” (Ellis et al., 2019; Havlik et al., 2020; Sarcedo et al., 2015). Microaggressions from CGCS peers, faculty, and staff affect all FGCS, but especially those who are also low-income and/or URM (Ellis et al., 2019; Havlik et al., 2020; House et al., 2020; Sarcedo et al., 2015). When honors program environments lack cultural sensitivity, FGCS, low-income, and URM students are more likely to feel stressed and isolated (Rinn & Plucker, 2019).

Factors that Promote Retention and Success

Targeted Initiatives Disproportionately Benefit Honors FGCS

One of the most effective ways to promote FGCS retention and success in honors programs is by tailoring outreach initiatives and services to the unique needs of this population (Adams & McBrayer, 2020; Elliott, 2014; Garriott & Nisle, 2017; Gibbons et al., 2019; Sarcedo et al., 2015; Stebleton & Soria, 2013). Honors programs are already known for providing services specific to honors students, as well as organizing opportunities for them to participate in high-impact activities (Cognard-Black & Spisak, 2019; Bowman et al., 2019). A challenge, however, is that FGCS tend to underutilize campus services and resources for reasons ranging from external obligations (as discussed earlier with work), to unawareness, to fear of burdening others (Chang et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2020). Therefore, programs that both develop FGCS-specific support mechanisms and simplify those students’ ability to engage with them are more likely to foster this population’s retention and success.

Positive Campus Relationships Can Mitigate Barriers to Success

Honors students are advantaged by the relationship-building opportunities built into their programs (Jarzombek et al., 2017; Rinn & Plucker, 2019). Relationships with more experienced collegiate peers can alleviate FGCS’ stress by providing them insight into the norms and behaviors needed to be successful in honors programs (Azmitia et al., 2018; Elliott, 2014; Garriott & Nisle, 2017; McCallen & Johnson, 2020). Mentorship programs are hailed as a best practice for fostering peer relationships (Garriott et al., 2017), but peer relationships that naturally develop can be effective as well (Demetriou et al., 2017). For FGCS who experience microaggressions, positive faculty or staff affirmations can disrupt negative internalized messages from the campus environment (Elliott, 2014; Ellis et al., 2019; Ives & Castillo-Montoya, 2020). As FGCS tend to be more racially and culturally diverse, cultivating an environment where they feel they can thrive and belong is key, and this starts with relationships.

Methodology

Study Design

I adopted a descriptive web-based survey design to achieve the purpose of my study and address its research question. As the research site has never systematically explored FGCS retention in their honors program, data collected via this method will enable leaders at this site to begin to understand potential relationships between FGCS and various factors researchers associate with collegiate program retention.

Instrumentation

The instrument used to collect data was an adapted version of the College Persistence Questionnaire (CPQ) (Davidson et al., 2009; Davidson et al., 2015). The CPQ is a widely used and validated instrument developed to predict the likelihood of a student’s future retention or attrition in collegiate programs or college altogether. For this study, I modified original CPQ items in two ways. First, I changed item language to direct respondents to reflect on their cumulative experiences leading up to the point in time of taking the survey, as opposed to reflecting solely on the present moment. As participants will have already achieved the construct of retention as it is defined in this study, modifying item language in this manner helped assess the influences of different retention factors throughout the honors career of a given respondent. The second modification I made was to specify the names of the honors program and institution in item language.

The final instrument contained 53 items which measured the following retention factors: academic integration, financial strain, social integration, degree commitment, collegiate stress, advising effectiveness, scholastic conscientiousness, institutional commitment, academic motivation, and academic efficacy. Additional demographic items inquired about respondents’ college generational status, gender, race/ethnicity, and college of enrollment. There was also one item for voluntary participation in the study incentive. Average completion time was estimated to be less than 15 minutes.

Sampling

Total population random sampling was used for this study. Although retained FGCS are the primary population of interest, the study compared retained FGCS to retained CGCS, hence, all autumn 2021-enrolled honors program participants undertaking at least their third year of enrollment were sampled. A total of 1,740 students (165 FGCS and 1,575 CGCS) met this criterion.

Data Collection

Prior to administering the survey, I pretested my instrument by conducting a 60-minute cognitive interview with an individual who identified as a retained FGCS in the honors program of interest. The respondent provided substantive feedback on the clarity of items, design layout of the survey, navigational experience, and completion time. The respondent was compensated for their time and consultation and did not participate in the present study.

After addressing the feedback raised during pretesting, I administered the official study survey via an email sent to all 1,740 retained students in the honors program. Those who consented to participation were taken to the survey, those who did not were free to exit the webpage. Participant recruitment and data collection occurred over a three-week period in September 2021-October 2021.

Data Analysis

The nature of the research question led me to explore factors significantly associated with program retention of retained FGCS by comparing them to retained CGCS. To do this, I performed independent samples t-test and chi-square test means comparison analyses for normal and non-normally distributed data, respectively. These procedures allowed me to statistically compare the mean of a variable in one group to the mean of a variable in another group. As both groups in the study achieved the construct of retention, these analyses highlighted differences in student’s cumulative experiences in the honors program up to the point of survey completion. In addition to means comparison analyses, I explored other trends in the descriptive data to identify what may need to be further studied by the research site in the future, namely, identifying which retention factor elicited the highest mean responses. Next, I share results and implications based on the outcomes of these procedures and analyses.

Results and Implications

Participant Characteristics

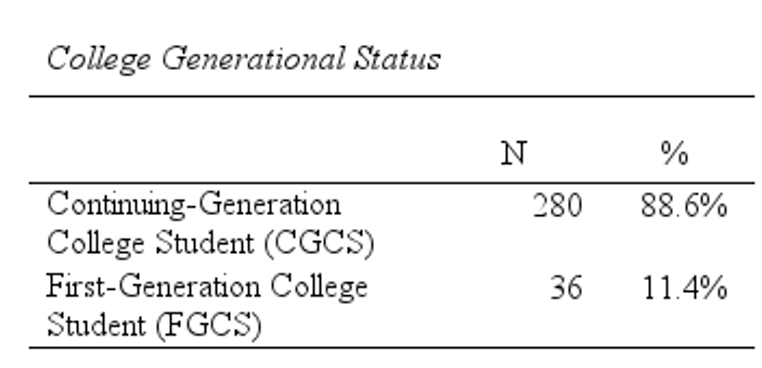

After the data collection period concluded I received 316 completed surveys from unique respondents (18.16% of the total population of FGCS and CGCS). Within the sample, 11.40% identified as FGCS, which was proportionate to the 9.43% share of FGCS in the overall population of retained honors students. The 36 FGCS participants in this study also made up 21.95% of all retained FGCS honors students. Refer to Table 1.1 for breakdown of final sample by college generational status.

Table 1.1

Breakdown of Study Participants by College Generational Status

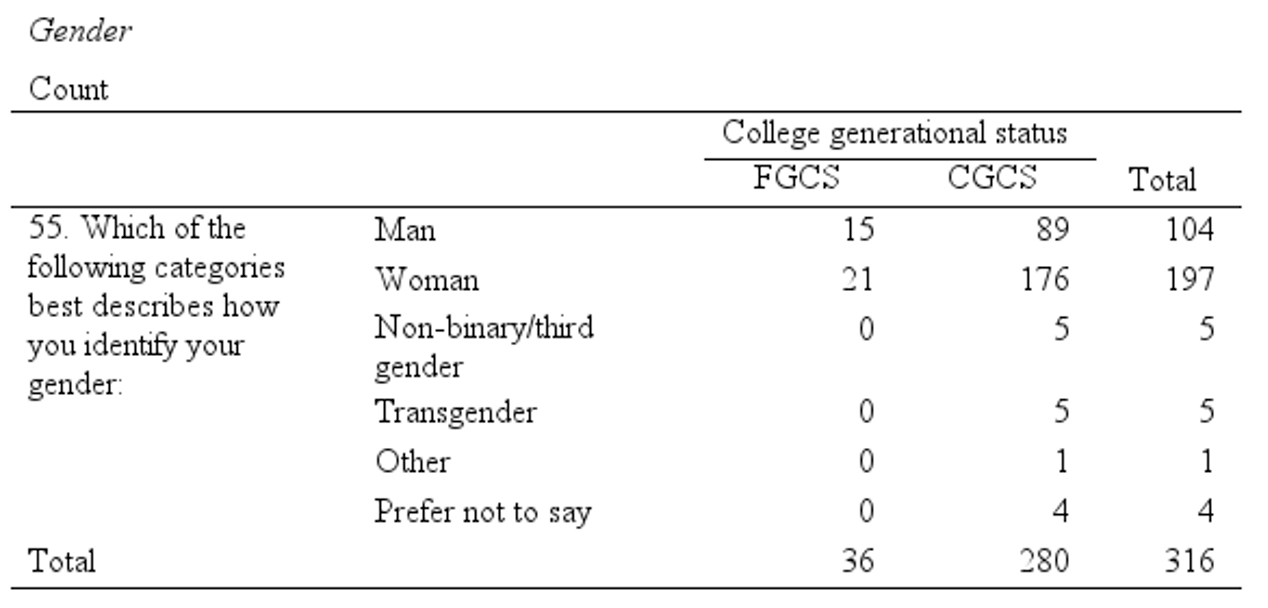

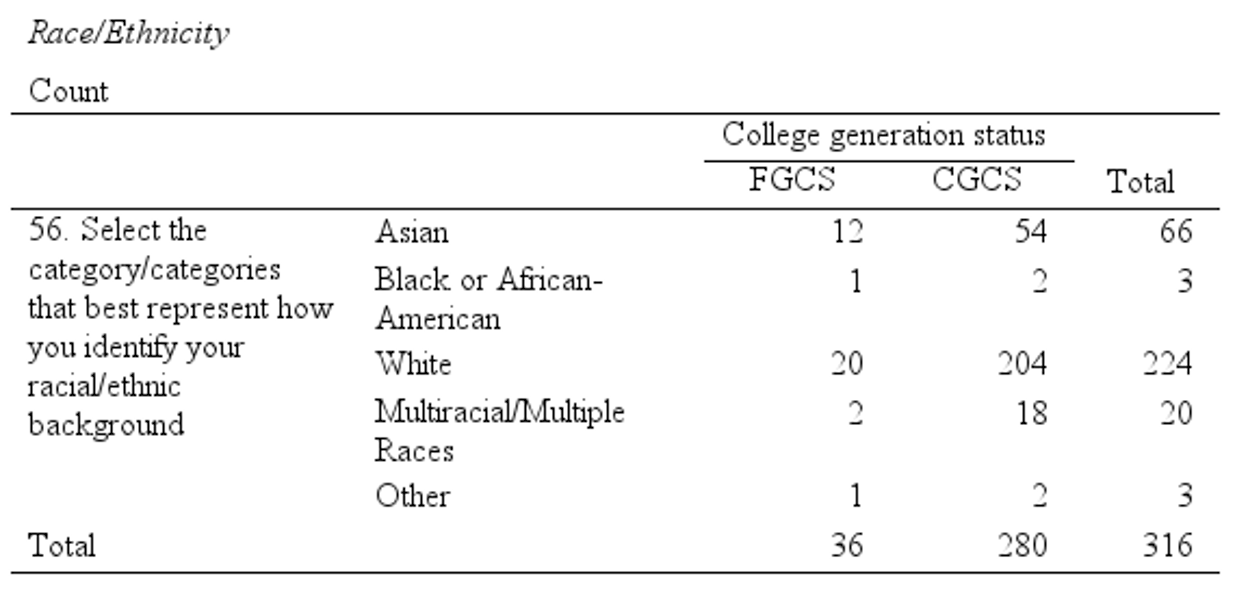

Participants’ reported gender and race/ethnicity are displayed in Tables 1.2 and 1.3 respectively.

Table 1.2

Breakdown of Study Participants by Gender

Note. Unlisted gender categories did not have any study participants.

Table 1.3

Breakdown of study participants by race/ethnicity

Note. Unlisted racial/ethnic categories did not have any study participants.

Results

Participant responses to the 53 nondemographic CPQ items were composited in SPSS according to alignment with the 10 retention factor variables. Histograms and quantile-quantile plots (QQ plots) were used to determine data normality of the responses of each of these 10 retention factor composites. Three contained normally distributed data (social integration, collegiate stress, and academic motivation) and seven contained nonnormally distributed data (academic integration, financial strain, degree commitment, advising effectiveness, scholastic conscientiousness, institutional commitment, and academic efficacy). Two sets of tests were performed to identify significant differences between the means of FGCS and CGCS participant responses: independent-samples t-test for normally distributed factors and chi-square test for non-normally distributed factors. Both sets of analyses adopted a 95% confidence level, indicating significance would be reached when p < .05.

Of the 10 retention factor variables measured, financial strain (p = .006) and advising effectiveness (p = .038), at a .05 significance threshold, were the only factors to reject the null hypothesis that there is not a difference between FGCS and CGCS. Eight retention factors measured in the CPQ did not achieve statistical significance at the p < .05 level. These factors were: academic integration, social integration, degree commitment, collegiate stress, scholastic conscientiousness, institutional commitment, academic motivation, and academic efficacy. These findings suggest FGCS and CGCS who participated in the study reported significantly different experiences related to financial strain and academic advising during their time enrolled in the honors program. A review of descriptive statistics also revealed the highest mean and median responses from all participants were in social integration. In other words, both groups rated their sense of belonging, shared values, similarity to others, and involvement behaviors during their time enrolled in the honors program most positively compared to their experiences across all other retention factors. Social integration differences between FGCS and CGCS were not statistically significant.

Implications

Financial Strain Was Felt More by FGCS than CGCS

The results of this study revealed retained FGCS endured greater financial strain during their time in the honors program than did their CGCS peers. They worried more about having enough money to support themselves, and it was more difficult for them to handle the costs of college during their time in honors. FGCS also struggled to purchase resources, such as books and supplies, and felt less able to engage in the same activities (e.g., honors-sponsored education abroad opportunities) as their peers due to finances.

The FGCS in this study weathered financial challenges while staying in honors because they found the program to fit with their undergraduate and postgraduation career goals (Miller & Dumford, 2018). The fact that honors degree pathways can sometimes lengthen a student’s degree completion timeline, which often has financial implications, reinforces this presumption of why the FGCS in this study persisted despite greater financial strain. Based on the review of literature on FGCS, many of the FGCS participants in this study likely worked during their time in the Honors Program (Adams & McBrayer, 2020; House et al., 2020), even though it may have limited their interactions with honors services, activities, and peers (Garriott et al., 2017; Gibbons et al., 2019; House et al., 2020; Stebleton & Soria, 2013). Essentially, retained FGCS persisted despite experiencing greater financial strain and the related challenges that come with it. This finding also calls attention to the effect of finances on prospective, current, and dropped out honors FGCS.

Access to Information and Quality Advising were Challenges for FGCS

The results of this study revealed retained honors program FGCS reported significantly less favorable experiences with academic advising than their CGCS counterparts. They expressed greater difficulty receiving vital information, and more challenge getting answers to questions related to the honors program throughout their careers. FGCS also reported lower satisfaction with the overall advising they received during their time in the program, and indicated they felt significantly less involved or considered in decision-making of processes such as course offering options.

Renewed Focus on Advising Practices Could Enhance FGCS’ Honors Success

The extant literature emphasized population-specific services and positive campus relationships as promoters of FGCS retention and success. On one hand, services or resources designed with FGCS’ unique characteristics and needs in mind increased the likelihood they will be used (Chang et al., 2020; Elliott, 2014). On the other hand, positive interactions with peers, faculty, and staff increases FGCS’ sense of belonging (Diehl, 2020; Ellis et al., 2019). Honors academic advising has the potential to combine both elements, and therefore could play an integral role in promoting the retention and success of FGCS in the honors program that is the subject of this research. In the context of honors students, academic advising quality can play a key role in whether a student decides to stay or leave a program (Kampfe et al., 2016; Swecker et al., 2013).

The results of this study demonstrated retained FGCS in the honors program remained in honors despite unideal advising experiences. FGCS often do not have the advantage of parents or guardians who can counsel them on how to navigate college bureaucracies to accomplish tasks or maximize campus resources—especially if their parents do not have any college-going experience (Havlik et al., 2020; Stebleton & Soria, 2013). With some honors majors being historically more challenging (Savage et al., 2014), and some majors fostering competitive rather than collaborative climates (Canning et al., 2020), advisors can be a point of support for those FGCS who struggle to successfully navigate these dynamics independently. According to the results of this study, addressing honors academic advising practices was another worthwhile area for the research site to address.

FGCS Felt Socially Connected to the Honors Program

The retention factor with the highest mean and median figures from both FGCS and CGCS was social integration. This connotes study participants found their social integration experiences to be most positive during their time enrolled in the honors program. Items in the social integration factor related to respondents’ sense of connectedness to honors program peers, faculty, and staff, and satisfaction with one’s social life in the program. Campus climates can be unwelcoming for FGCS (Azmitia et al., 2018; Rinn & Plucker, 2019), but positive campus relationships can counteract this experience by invalidating harmful messages (Elliott, 2014; Ellis et al., 2019; Ives & Castillo-Montoya, 2020). It is encouraging that FGCS in this study, who have remained in the program for three years or longer, benefited from the research site’s deliberate efforts to help students build relationships among themselves, faculty, and staff. Even though FGCS’ social integration experiences did not statistically differ from CGCS,’ this finding provided insight into what has been consequential with this population during their retention.

Study Limitations

As with most studies, the present study is subject to several limitations. First, the data analyses were successful in revealing which retention factors FGCS and CGCS differed or did not differ across, but they were limited in conveying the underlying reasons. This limitation was to be expected, as most exploratory quantitative research designs concentrate on discovering macro-level patterns and associations rather than specific causal relationships (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The review of literature provided some explanation for participants’ responses in this study, but the methodology precluded me from gaining richer qualitative insight.

Another limitation of this study was that retained FGCS were only compared to retained CGCS to achieve the study objective. Comparing retained FGCS to unretained FGCS could have provided a more thorough understanding of what distinguishes the former from other comparable populations in the program. Unretained honors FGCS at this institution were a complicated population to engage. Students often pause honors participation with plans to rejoin later; therefore, it is difficult to track those who have permanently dropped out versus temporarily. Further, some unretained FGCS left the institution altogether, making it challenging to locate them and incentivize participation in this study. Comparisons to retained CGCS produced helpful, actionable information for the research site, but an accessible third comparison group could have resulted in more robust findings.

Finally, the small sample size and targeted context of the collected data means the implications of this study cannot be dependably extrapolated to honors FGCS outside of the research site. The information gathered from 21.88% of all retained FGCS will enhance the decision-making of this research site’s leaders, but definitive conclusions from this study regarding FGCS in other collegiate honors settings should be done carefully and sparingly.

Research Site Recommendations

The present study illuminated the roles of financial strain, academic advising, and social integration on retained FGCS in the honors program of a large public institution. Informed by scholarly literature and the study’s implications, I proposed five recommendations for the research site to support their efforts to better promote the retention and success of FGCS. Specifically, I advised that program leaders should:

- create flexible and low-cost alternatives to major Honors activities and programming;

- implement initiatives and resources that address student finances;

- examine and address honors advising practices;

- develop accessible repository of critical honors academic affairs information; and

- bolster efforts to foster social integration among honors FGCS.

The following sections briefly review of each of these recommendations.

Create Flexible and Low-Cost Alternatives to Major Honors Activities and Programming

FGCS are more likely than CGCS to have to work during college (Adams & McBrayer, 2020; Havlik et al., 2020; House et al., 2020). Work obligations may restrict the extent to which FGCS can engage with campus support services and activities (Garriott et al., 2017; Stebleton & Soria, 2013). Research on honors student persistence supports simplifying the ways in which students can utilize program services or resources (Nichols et al., 2013). The research site’s ability to provide alternative time offerings or formats for key services and activities can significantly benefit their FGCS, especially those with unobliging work or personal obligations.

Relatedly, as FGCS are more likely than CGCS to be lower income, participation in cost-associated honors activities can be challenging, regardless of how impactful they may be. Evidence-based high-impact practices the research site’s honors program offers—such as education abroad, service-learning, or honors-designed housing—all require economic capital. The research site can disrupt some of these disparities in opportunity by providing flexible and more cost-effective alternatives to these transformative experiences.

Implement Initiatives and Resources Addressing Student Finances

A multi-institutional study with responses from 12,295 students enrolled in four-year institutions found FGCS to report significantly lower financial knowledge and financial self-efficacy (Rehr et al., 2022). Partnering with campus units that specialize in financial wellness and financial aid to provide resources and information at key touchpoint moments, such as orientation or first-year seminar, can provide yet another option for supporting financially strained students in the research site’s honors program. Certainly, more direct forms of financial assistance, such as grants and scholarships, can immediately reduce students’ financial strain and free up more time for them to participate in honors or other campus opportunities (Garriott & Nisle, 2017; Gibbons et al., 2019). Directly or indirectly, acknowledging issues related to finance for FGCS enhances the likelihood of program persistence.

Examine and Address Honors Advising Practices

The FGCS in this study rated their academic advising experiences as honors students significantly less positively than did their CGCS counterparts. This finding also raised questions regarding the experiences of FGCS who did not persist in the research site’s honors program, and the role advising could have had in either promoting or preventing their attrition. The research site does not have dominion over academic advising; each sub-college at the institution designates advisors to work with honors populations. This decentralized structure carries many benefits but can also complicate efforts to implement uniform standards across disparate units and staff members. I provided the research site a couple of suggestions for addressing this issue: first, identify the specific problems points for FGCS by conducting focus groups, and second, take leadership in equipping honors advisors with concrete tools to improve interactions with FGCS, such as workshops and professional development. The research site’s institution boasts a host of resources the site can draw from to enact these measures.

Develop Accessible Repository of Critical Honors Academic Affairs Information

FGCS in this study reported lower satisfaction with how the honors program communicated key information, such as academic rules, degree requirements, campus opportunities compared to CGCS. They also reported that it was difficult to receive answers to advising-related questions. To address this issue, I recommended the research site develop a “one-stop-shop” central repository for advising and other academic affairs information relevant to honors students. First, they can take inventory of all the current outlets, formats, and frequencies of any honors communications currently disseminated to honors students. This will help the research site to establish a baseline for how students currently receive or can access this kind of information. Next, they can determine what types of information they deem most critical for honors students and compile it onto one central platform. This can take the form of a new page on their main website, or one central Blackboard page. As FGCS may be less inclined to use campus resources for fear of burdening others (Chang et al., 2020), providing a low barrier means to independently access essential information or answers to frequently asked questions is a simple solution with high payoff.

Bolster Efforts to Foster Social Integration Amongst Honors FGCS

A predominant reason for honors students’ superior collegiate outcomes relative to non-honors students is the peer and faculty relationship-building opportunities characteristic of honors programs (Cuevas et al., 2017; Jarzombek et al., 2017; Miller & Dumford, 2018; Rinn & Plucker, 2019). The retained FGCS who participated in this study reported strong connectedness to honors peers, faculty, and staff throughout their time in the program. This suggests, at least on some level, social integration has and may continue to play a role in the retention and success of past, current, and future FGCS in the honors program at the focus of this study.

Based on the results of this study, I advised the research site to consider ways to strengthen social integration amongst FGCS in their honors program. A consistently cited practice in FGCS retention literature is peer mentorship. FGCS who develop these relationships early on are more likely to learn and mimic the norms and behaviors needed to be successful in college (Azmitia et al., 2018; Elliott, 2014; McCallen & Johnson, 2020). Formal mentorship programs (Garriott et al., 2017) and mentorship relationships that naturally occur (Demetriou et al., 2017) can respectively be effective, so long as opportunities for mentorship-type relationships to develop are being intentionally cultivated. Supporting this recommendation, I provided the research site suggestions on how they could pilot a peer mentorship experience connecting new incoming honors FGCS to upper-class-ranked FGCS in their honors program.

Recommendations for Future Research and Assessment

To build on the present research, future studies on this topic can investigate the precise reasons financial strain and academic advising experiences were significantly different between retained FGCS and CGCS. A qualitative study can illuminate more details around those and other aspects related to FGCS’ experiences in the program. As social integration was rated most favorably among FGCS, a future study can similarly probe into which aspects of it were most influential in their ability to persist as an honors student.

The methodology and accompanying analyses performed in this study can be applied to other demographic groups participating in honors programs. Should the research site or another similarly situated entity find interest in examining factors associated with the retention of a certain demographic of students, the present study may provide a helpful initial framework.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to explore factors associated with the retention of FGCS in the honors program of a large public research institution. The results of the study concluded that two out of 10 factors measured through the adapted CPQ instrument, financial strain and academic advising effectiveness, featured significantly different responses between FGCS and CGCS counterparts. Further, all FGCS and CGCS study participants rated their social integration experiences the highest out of all other retention factors. Based on these findings, I discussed implications, provided recommendations to the research site, and highlighted opportunities for future research and assessment.

The results of this study supported recent scholarly literature on collegiate honors programs and FGCS retention and success by revealing that efforts tied to finances, academic affairs (i.e., academic advising), and belonging can make significant inroads towards the success of this population. Most of all, this study illuminated the barriers that retained FGCS in research site’s honors program have been enduring, and overcoming, relative to their CGCS peers. The findings generated through this study will not only benefit the efficacy of the research site’s honors program operations, but hopefully lends some insight to practitioners tasked with supporting this population on their campus.

References

Adams, T. L., & McBrayer, J. S. (2020). The lived experiences of first-generation college

students of color integrating into the institutional culture of a predominantly white institution. The Qualitative Report, 25(3), 733–756.

Azmitia, M., Sumabat‐Estrada, G., Cheong, Y., & Covarrubias, R. (2018). “Dropping out is not

an option”: How educationally resilient first-generation students see the future. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2018(160), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20240

Bowman, N. A., & Culver, K. (2018). When do honors programs make the grade? Conditional

effects on college satisfaction, achievement, retention, and graduation. Research in Higher Education, 59(3), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9466-y

Brimeyer, T. M., Schueths, A. M., & Smith, W. L. (2014). Who benefits from honors: An

empirical analysis of honors and non-honors students’ backgrounds, academic attitudes, and behaviors. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 15(1), 69–84.

Cabrera, A., Nora, A., & Castaneda, M. (1993). College persistence: Structural equations

modeling test of an integrated model of student retention. The Journal of Higher

Education, 64(2), 123–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2960026

Chang, J., Wang, S., Mancini, C., McGrath-Mahrer, B., & Orama de Jesus, S. (2020). The

complexity of cultural mismatch in higher education: Norms affecting first-generation college students’ coping and help-seeking behaviors. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(3), 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000311

Clark, C., Schwitzer, A., Paredes, T., & Grothaus, T. (2018). Honors college students’

adjustment factors and academic success: Advising implications. NACADA Journal, 38(2), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.12930/NACADA-17-014

Cognard-Black, A. J., & Spisak, A. L. (2019). Creating a profile of an honors student: A

comparison of honors and non-honors students at public research universities in the United States. Journal of National Collegiate Honors Council-Online Archive, 20(1) 123–157. 623.

Cuevas, A., Schreiner, L., Kim, Y., & Bloom, J. (2017). Honors student thriving: A model of

academic, psychological, and social wellbeing. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 18(2), 79–119. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/597

Davidson, W. B., Beck, H. P., & Grisaffe, D. B. (2015). Increasing the institutional commitment

of college students: Enhanced measurement and test of a nomological model. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025115578230

Davidson, W. B., Beck, H. P., & Milligan, M. (2009). The College Persistence Questionnaire:

Development and validation of an instrument that predicts student attrition. Journal of

College Student Development, 50(4), 373–390.

Demetriou, C., Meece, J., Eaker-Rich, D., & Powell, C. (2017). The activities, roles, and

relationships of successful first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 58(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0001

Diehl, R. H. (2020). Stories of greatness and honor: A narrative inquiry of first-generation

college students who are community college honors program graduates (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Nebraska-Lincoln). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Elliott, D. C. (2014). Trailblazing: Exploring first-generation college students’ self-efficacy

beliefs and academic adjustment. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Student Transition, 26(2), 29–49.

Ellis, J. M., Powell, C. S., Demetriou, C. P., Huerta-Bapat, C., & Panter, A. T. (2019).

Examining first-generation college student lived experiences with microaggressions and microaffirmations at a predominately White public research university. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000198

Garriott, P. O., & Nisle, S. (2017). Stress, coping, and perceived academic goal progress in

first-generation college students: The role of institutional supports. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(4), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000068

Gibbons, M. M., Rhinehart, A., & Hardin, E. (2019). How first-generation college students

adjust to college. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 20(4), 488–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025116682035

Havlik, S., Pulliam, N., Malott, K., & Steen, S. (2020). Strengths and struggles: First-generation

college-goers persisting at one predominantly white institution. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 22(1), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025117724551

House, L. A., Neal, C., & Kolb, J. (2020). Supporting the mental health needs of first generation

college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 34(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2019.1578940

Ives, J., & Castillo-Montoya, M. (2020). First-generation college students as academic learners:

A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 139–178. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319899707

Jarzombek, M. J., McCuistion, K. C., Bain, S. F., Guerrero, D., & Wester, D. B. (2017). The

effect of an honors college on retention among first year students. Research in Higher Education Journal, 33, 1–16.

Kampfe, J. A., Chasek, C. L., & Falconer, J. (2016). An examination of student engagement and

retention in an honors program. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 17(1), 219–235.

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., Bowman, N. A., Seifert, T. A., & Wolniak, G. C. (2016).

How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works (Vol. 1). John Wiley & Sons.

McCallen, L. S., & Johnson, H. L. (2020). The role of institutional agents in promoting higher

education success among first-generation college students at a public urban university. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13(4), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000143

Means, D. R., & Pyne, K. B. (2017). Finding my way: Perceptions of institutional support and

belonging in low-income, first-generation, first-year college students. Journal of College Student Development, 58(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0071

Miller, A. L., & Dumford, A. D. (2018). Do high-achieving students benefit from honors college

participation? A look at student engagement for first-year students and seniors. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 41(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353218781753

National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). First-generation students: College, access,

persistence, and postbachelor’s outcomes. (Rep.). https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018421.pdf

Nichols, T. J., & Chang, K.-L. M. (2013). Factors influencing honors college recruitment,

persistence, and satisfaction at an upper-midwest land grant university. Journal of National Collegiate Honors Council-Online Archive, 105–127. 399.

Núñez, A.-M., & Sansone, V. A. (2016). Earning and learning: Exploring the meaning of work

in the experiences of first-generation Latino college students. The Review of Higher Education, 40(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2016.0039

Phillips, L., Stephens, N., Townsend, S., & Goudeau, S. (2020). Access is not enough: Cultural

mismatch persists to limit first-generation students’ opportunities for achievement throughout college. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1112–1131. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000234

Plominski, A. P., & Burns, L. R. (2018). An investigation of student psychological wellbeing:

Honors versus nonhonors undergraduate education. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17735358

Rehr, T.I., Phillips, E.R., Abukar, Z., & Meshelemiah, J.C.A. (in press). Financial wellness of

first-generation college students. College Student Affairs Journal.

Rinn, A. N., & Plucker, J. A. (2019). High-ability college students and undergraduate honors

programs: A systematic review. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(3), 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219855678

Salisbury, M. H., Pascarella, E. T., Padgett, R. D., & Blaich, C. (2012). The effects of work on

leadership development among first-year college students. Journal of College Student Development, 53(2), 300–324.

Sarcedo, G. L., Matias, C. E., Montoya, R., & Nishi, N. (2015). Dirty dancing with race and

class: Microaggressions toward first-generation and low income college students of color. Journal of Critical Scholarship on Higher Education and Student Affairs, 2(1), 1–17.

Savage, H., Raehsler, R. D., & Fiedor, J. (2014). An empirical analysis of factors affecting

honors program completion rates. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 15(1), 115–128.

Singell, L. D., & Tang, H.-H. (2012). The pursuit of excellence: An analysis of the honors

college application and enrollment decision for a large public university. Research in Higher Education, 53(7), 717–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9255-6

Strayhorn, T. L. (2006). Factors influencing the academic achievement of first-generation

college students. NASPA Journal, 43(4), 82–111.

Stebleton, M. J., & Soria, K. (2013). Breaking down barriers: Academic obstacles of

first-generation students at research universities. The Learning Assistance Review, 17(2), 7–19. https://hdl.handle.net/11299/150031

Swecker, H. K., Fifolt, M., & Searby, L. (2013). Academic advising and first-generation college

students: A quantitative study on student retention. NACADA Journal, 33(1), 46–53.

Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Yaeger, P. M., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1996). First-

generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Research in Higher Education, 37(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01680039

Vuong, M., Brown-Welty, S., & Tracz, S. (2010). The effects of self-efficacy on academic

success of first-generation college sophomore students. Journal of College Student

Development, 51(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0109

Wawrzynski, M. R., Madden, K., & Jensen, C. (2012). The influence of the college environment

on honors students’ outcomes. Journal of College Student Development, 53(6), 840–845.

Author Bio

Zayd Abukar, Ed.D. (he/him/his) serves as the Assistant Director for Scholarship and Supplemental Academic Services within the Office of Diversity and Inclusion (ODI) at The Ohio State University. He provides strategic leadership and management of a student services unit that provides academic and financial aid support services to students in ODI programs. Dr. Abukar’s research interests span the intersections of leadership, organizational behavior, and underrepresented college student success.