Duke D. Biber & Dena Kniess

College of Education

University of West Georgia

A Model for Wellness

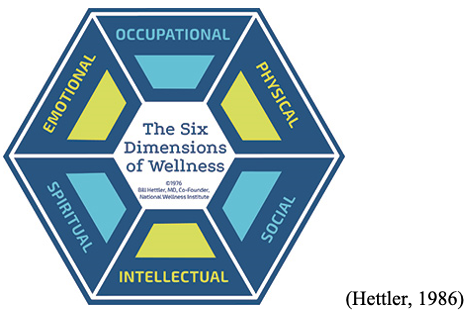

Over the past decade, graduate student wellness has received increased research and practical attention. The National Wellness Institute defines wellness as “an active process through which people become aware of, and make choices toward, a more successful existence” (NWI, 2020). There are six specific domains of wellness: occupational, physical, social, intellectual, spiritual, and emotional (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Each of these domains of wellness are interrelated, meaning that improvements in one domain often result in improvements in another. Furthermore, wellness is a conscious process that can be pursued and improved. While plenty of research and application has focused on wellness promotion, graduate students continue to struggle with all components of wellness.

Graduate Student Wellness

Reports from UC Berkeley (2014) and the University of Arizona (2015) indicate high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression across graduate student cohorts. A study examining 26 institutions revealed that graduate students are six times more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression when compared to the general population (Evans et al., 2018). Furthermore, nearly 70% of graduate students report experiencing the negative impacts of stress during their graduate education (El-Ghoroury et al., 2012). These mental and emotional health variables can impact other areas of student wellness, including sleep behavior, physical well-being, and satisfaction with life (Alleyne et al., 2010; Lund et al., 2010; Ogunsanya et al., 2018). Furthermore, stress, anxiety, and depression can negatively impact perceptions of social support and resultant retention through graduate school (McKinney, 2017). The inability to successfully cope with stress, anxiety, depression and perceived isolation often associated with graduate school can lead to student burnout (Evans et al., 2018).

Burnout can be defined as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” (p. 399) that includes cynicism, emotional exhaustion, and lack of personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 2001). Graduate students who experience burnout may disengage from their peers, advisor, and program. Barreria et al. (2018) found graduate student mental health varies widely across graduate programs. Burnout and stress in graduate students can lead to academic issues, such as difficulty concentrating, imposter syndrome, and suicidal ideation (Flaherty, 2018). If left unaddressed, these issues can lead to dropping out of one’s graduate program, severe depression, or suicide (MacLean et al. 2016; Mortier et al., 2018).

Student Help Seeking Behavior

There are a wide variety of resources available to graduate students on campus, one of which is counseling and psychological services. However, research indicates that college students are not always motivated or willing to seek counseling (Topkaya, 2014). Furthermore, students who are more anxious tend to exhibit greater stigma and less likelihood to see a counselor when in need (Cheng et al., 2015; Kim & Zane, 2015). Students often do not have mental health literacy, or the knowledge about mental health issues that is necessary to help them recognize symptoms, manage symptoms through self-care or counseling, and prevent further problems (Kutcher, 2016). This also includes the ability to distinguish clinical mental health issues from regular stress or anxiety, as well as the risk factors and available resources, on attitudes toward seeking professional help (Jorm et al., 1997). Low mental health literacy is positively related to anxiety and stress, and is negatively related to help-seeking attitudes and behaviors in students (Coles & Coleman, 2010; Kim et al., 2015; Stansbury et al., 2011). While it would be ideal for graduate students to regularly use counseling services, there is often a waitlist, reluctance, or stigma to do so (LeViness et al., 2017). It is important to promote graduate student coping, psychological well-being, and support as a method to reduce burnout and drop-out, and promote overall student wellness (Gardner, 2010).

Promoting Wellness through Work-Life Integration

Recently, there has been a shift in emphasis from work-life balance to that of work-life integration as a method of promoting wellness. Work-life integration is “an approach that creates more synergies between all areas that define ‘life’: work, home/family, community, personal well-being, and health” (UC Berkeley). Work-life balance often creates a sense of competition in which an individual struggles to rationalize which area of life deserves time, attention, or care, whereas work-life integration is a holistic perspective in which every area of life warrants attention for overall well-being (Kossek et al., 2014). Work-life integration can be learned and pursued through goal-setting, lifestyle modification, and accountability, which can be promoted through health coaching.

One growing field of research and application that can improve student wellness and retention is health coaching. The purpose of this manuscript is to educate faculty, staff, and students on the role health and wellness coaching can play in graduate student academic performance and overall wellness. In order to understand health coaching, it is necessary to understand the multidimensional nature of wellness.

The Rationale for Health and Wellness Coaching

Health and wellness coaching is “the practice of health education and health promotion within a coaching context, to enhance the wellbeing of individuals and to facilitate the achievement of their health-related goals” (Palmer et al., 2003, pp. 91). Rather than clinical counseling serving as an intervention, health and wellness coaching aims to guide each client to develop their own wellness-related goals. As clients develop both short- and long-term goals, the health coach provides practical techniques and strategies to develop confidence and manage personal wellness with autonomy (Thom, 2019).

Health and wellness coaching has become more popular as a resource for students, faculty, and staff throughout higher education due to the focus on client decision-making, self-management, and effectiveness of such services across a wide variety of populations (Sherifali et al., 2016; Thom, 2019; Willard-Grace et al., 2015). Universities have begun adopting health and wellness coaching to provide services to students exhibiting sub-clinical symptoms as well as training and certificates for students to provide services to others (Sforzo et al., 2018). Health and wellness coaching is a multi-faceted service that can promote healthy self-regulation of behaviors and reduce many of the physical, psychological, social, and financial struggles students often face when transitioning to graduate school (Fried & Irwin, 2014; Sforzo et al., 2018).

Promoting Campus-Wide Health and Wellness Coaching

Health and wellness coaching is a viable option for graduate students regardless of program of study. The University of West Georgia has developed a model in which students who do not meet criteria for clinical diagnosis are referred to certified health and wellness coaches without charge (Biber et al., 2018). The campus also has an Exercise is Medicine on Campus™ program in which certified health and wellness coaches provide holistic care with students already engaging in an exercise program (Biber et al., 2018). This helps reduce the waitlist for counseling for students who are clinical in nature, while also providing ongoing support for students with a focus on wellness promotion.

Furthermore, health and wellness coaches can provide cognitive and behavioral strategies through education for individuals and groups to improve personal wellness management (Wolever et al., 2013). Campuses can even promote technology-based health and wellness coaching as a method of maintaining care during holidays, breaks, or for graduate students who work full-time and need coaching after regular business hours. The goal of health and wellness coaching is to promote behavior change through a client-centered approach that often uses motivational interviewing, journaling, self-care strategies and the transtheoretical model to energize the client to solve their own problems (Swarbrick et al., 2011). Health and wellness coaching can be used to complement services that are already provided by counseling and psychological services, the campus recreation center, and the student health center (Saginak, 2020).

Campus Resources to Complement Health and Wellness Coaching (Dena)

A number of resources exist to complement health coaching. Oswalt and Riddock (2007) indicated graduate students were interested in various coping strategies, such as massage, yoga, or meditation. There are various resources on meditation, such as apps, such as the Headspace and Calm Apps that offer three-to-five minute guided meditations in addition to YouTube videos on meditation. Campuses may also offer group fitness classes, such as yoga or mindfulness training. Area libraries may offer community training events, such as mindfulness or stress management sessions. A review of mindfulness-based self-compassion interventions, found that such techniques are just as effective as counseling and treatment in promoting self-regulation of health behaviors (Biber & Ellis, 2019). Health and wellness coaches can promote the aforementioned resources for at-home practice or during sessions to help clients realize the value and benefit of each.

Future Research/Application

Overall well-being is critical to the success of graduate students. As faculty, staff, undergraduate and graduate students prepare to return to campus, all six dimensions of wellness, occupational, emotional, spiritual, physical, intellectual, and social need avenues for support. Questions for campuses to consider are:

- What resources are available to faculty, staff, and students to support the six dimensions of wellness? What are the costs of these resources? How are these resources promoted?

- What are the needs of faculty, staff, and students occupationally, socially, emotionally, physically, intellectually, and spiritually?

- How are these resources delivered? Are multiple modalities considered for faculty, staff, and students who are on campus or at a distance? What connections are there to local resources in the surrounding community?

- What peer-to-peer resources exist for faculty, staff, and students that support the six dimensions of wellness?

References

Barreria, P., Basilico, M., & Bolotnyy, V. (2018). Graduate student mental health: Lessons from American economics departments. Working paper. Harvard Department of Economics.

Biber, D. D., & Ellis, R. (2019). The effect of self-compassion on the self-regulation of health behaviors: A systematic review. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(14), 2060-2071. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317713361

Biber, D. D., Brandenburg, G., Stewart, B., Knoll, C., Merrem, A. M., & McBurse, S. (2018). The wolf wellness lab: A model for community health and wellness promotion. GAHPERD, 50(2), 4-11.

Cheng, H., McDermott, R. C., & Lopez, F. G. (2015). Mental health, self-stigma, and help-seeking intentions among emerging adults: An attachment perspective. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 463–487. doi:10.1177/0011000014568203

Coles, M. E., & Coleman, S. L. (2010). Barriers to treatment seeking for anxiety disorders: initial data on the role of mental health literacy. Depression and Anxiety, 27(1), 63-71. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20620

El-Ghoroury, N. H., Galper, D. I., Sawaqdeh, A., & Bufka, L. F. (2012). Stress, coping, and barriers to wellness among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(2), 122-134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028768

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Stress & burnout in graduate students: The role of work-life balance and mentoring relationships. The FASEB Journal, 32(1), 535-527.

Flaherty, C. (2018). A very mixed record on grad student mental health. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/12/06/new-research-graduate-student-mental-well-being-says-departments-have-important

Fried, R. R., & Irwin, J. D. (2016). Calmly coping: A motivational interviewing via co-active life coaching (MI-VIA-CALC) pilot intervention for university students with perceived levels of high stress. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 14(1), 16-33. URL: http://ijebcm.brookes.ac.uk/

Gardner, S. K. (2010). Contrasting the socialization experiences of doctoral students in high- and low-completing departments: A qualitative analysis of disciplinary contexts at one institution. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(1), 61-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11778970

Hettler, B. (1986). Strategies for wellness and recreation program development. New Directions for Student Services, 34, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.37119863404

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182–186.

Kim, J. E., Saw, A., & Zane, N. (2015). The influence of psychological symptoms on mental health literacy of college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85, 620–630. doi:10.1037/ort0000074

Kim, J. E., & Zane, N. (2015). Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and White American students in psychological distress: Application of the health belief model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22, 311–321. doi:10.1037/cdp0000056

Kossek, E. E., Valcour, M., & Lirio, P. (2014). The sustainable workforce: Organizational strategies for promoting work–life balance and wellbeing. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (pp. 1-24). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 154-158. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609

LeViness, P., Bershad, C., & Gorman, K. (2017). The association for university and college counseling center directors annual survey. Retrieved from https://www. aucccd. org/assets/documents/Governance/2017% 20aucccd% 20surveypublicapr26. Pdf.

MacLean, L., Booza, J., & Balon, R. (2016). The impact of medical school on student mental health. Academic Psychiatry, 40(1), 89-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0301-5

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

McKinney, B. (2017). Associations among Social Support, Life Purpose and Graduate Student Stress. VAHPERD Journal, 38(2), 4-10.

Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., … & Nock, M. K. (2018). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among college students and same-aged peers: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(3), 279-288. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1481-6

National Wellness Institute. (2020). The six dimensions of wellness. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nationalwellness.org/resource/resmgr/pdfs/sixdimensionsfactsheet.pdf

Ogunsanya, M. E., Bamgbade, B. A., Thach, A. V., Sudhapalli, P., & Rascati, K. L. (2018). Determinants of health-related quality of life in international graduate students. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10(4), 413-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2017.12.005

Oswalt, S.B. & Riddock, C.C. (2007). What to do about being overwhelmed: Graduate students, stress and university services. College Student Affairs Journal, 27(1), 24-44.

Palmer, S., Tubbs, I., & Whybrow, A. (2003). Health coaching to facilitate the promotion of healthy behaviour and achievement of health-related goals. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 41(3), 91-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2003.10806231

Saginak, K. (2020). Health coaching vs. counseling: What’s the difference? Kresser Institute for Functional and Evolutionary Medicine. Retrieved from https://kresserinstitute.com/

Sherifali, D., Viscardi, V., Bai, J. W., & Ali, R. M. U. (2016). Evaluating the effect of a diabetes health coach in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 40(1), 84-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.10.006

Sforzo, G. A., Kaye, M. P., Todorova, I., Harenberg, S., Costello, K., Cobus-Kuo, L., … & Moore, M. (2018). Compendium of the health and wellness coaching literature. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(6), 436-447. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617708562

Smith, E. & Brooks, Z. Graduate Student Mental Health (University of Arizona, 2015) http://nagps.org/nas/content/live/acpadevelopmen/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/NAGPS_Institute_mental_health_survey_report_2015.pdf

Stansbury, K. L., Wimsatt, M., Simpson, G. M., Martin, F., & Nelson, N. (2011). African American college students: Literacy of depression and help seeking. Journal of College Student Development, 52, 497–502. doi:10.1353/csd.2011.0058

Swarbrick, M., Murphy, A. A., Zechner, M., Spagnolo, A. B., & Gill, K. J. (2011). Wellness coaching: A new role for peers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(4), 328. doi: 10.2975/34.4.2011.328.331

Thom, D. H. (2019). Keeping pace with the expanding role of health coaching. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34, 5-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4730-1

Topkaya, N. (2014). Gender, self-tigma, and public stigma in predicting attitudes toward psychological help-seeking. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 14(2), 480-487.

UC Berkeley Graduate Assembly. Graduate Student Happiness and Well-being Report http://ga.berkeley. edu/wellbeingreport (2014).

Willard-Grace, R., Thom, D. H., Hessler, D., Bodenheimer, T., & Chen, E. H. (2015). Health coaching to improve control of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia for low-income patients: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Family Medicine, 28(1), 38-45.

Wolever, R. Q., Simmons, L. A., Sforzo, G. A., Dill, D., Kaye, M., Bechard, E. M., … & Yang, N. (2013). A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: Defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 2(4), 38-57.