Sarah Jones

Assistant Professor, University of West Georgia

Shanna Smith

Assistant Professor, University of West Georgia

Abstract

Assessment, evaluation, and research (AER) are central focuses within higher education; however, researchers and practitioners often find themselves researching and interacting with participants outside of their own identity/ies. Providing historical perspectives on access, inclusion, and equity, and reviewing stages of ally development, this article offers thoughtful ways in which practitioners can engage in AER with participants from historically underrepresented identities. Perspectives in this article emphasize positivist approaches and empirically-driven research. Topics regarding self-interest and saviorism, positionality, altruism, social justice, and aspiring allyship are explored.

Researching Outside Our Identities

As we engage more with assessment, evaluation, and research (AER) of higher education on various levels it is possible that the primary assessor, evaluator, or researcher will be gathering data from individuals and groups whose salient identity/ies are outside their own. Since this dynamic is not uncommon, it is necessary to acknowledge the inherent power differential between the conductor of AER and the participant; as well as the inherent biases we as conductors hold toward individuals and groups outside our own. Though acknowledging the differential in power is necessary, it is not enough; instead we need to dig deeper. In this paper we will address the history of our experience with, and some suggestions for, conducting AER with participants outside our identities.

Historical Perspectives on Access, Inclusion, and (in)Equity

By examining the “other” without placing students and groups in historical and modern frameworks of interdisciplinary approaches, white researchers have traditionally taken an ahistorical approach to the study of Students of Color in higher education (Hernandez, 2016). But more recently, in an attempt to understand current issues in higher education regarding Students of Color and other historically underrepresented populations, researchers have called for an increased recognition of backgrounds, circumstances, experiences, and outcomes (Harper, Patton, & Wooden, 2009; Thelin, 2011). An area of concern for Students of Color is that historically white colleges and universities often overlook and/or ignore their needs out of ignorance, racism, color-blind ideologies, and white normativity (Bonilla-Silva, 2017; Harper et al., 2009; Heisserer & Perette, 2002; McCoy & Rodricks, 2015). Embracing an historical perspective uncovers these and other inequities while creating space to appropriately discuss and explore current climate and innovative solutions by policy makers, administrators, researchers, and faculty.

Via the lens of Critical Race Theory (CRT), Harper et al. (2009) examined the history of higher education for Students of Color, specifically African Americans, in the United States. Their study included an examination of policy issues that influenced access, equity, and retention. Access to higher education for People of Color was first granted in the early 1820s, and was originally intended to educate freed slaves at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) (Harper et al., 2009). The first historically Black college or university (HBCU) was not chartered for another three decades, however, until 1853 when the Ashmun Institute (now Lincoln University) opened and vowed to increase “the scientific, classical, and theological education of colored youth of the male sex” (Farrison, 1977, p. 403).

Despite a population in the millions and more than 40 years of access to higher education, only 28 African Americans held a college degree after the Civil War (Harper, 2009). While The Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 provided access for public higher education via federal funding, it was not until The Morrill Act of 1890 that African Americans had access to equal funding for higher education, but in only 17 of the 42 states. More than 60 years later and after the Brown vs Board of Education ruling in 1954 the Jim Crow South was ordered to desegregate, however efforts to do so by government and institutions were “largely a matter of halfhearted, token compliance” (Thelin, 2011, p. 304). Consequently, despite some legislative advances, “Black students remained marginal and proportionately underrepresented at almost all racially desegregated campuses in the United States” (Thelin, 2011, p. 305). Tracing inequitable opportunity to access higher education underscores the significant and influential racial issues still present in contemporary higher education.

Persistent inequity in U. S. society has perpetuated racism within social, political, cultural, and educational realms (Bonilla-Silva, 2001; Harper et al., 2009). However, compared to Jim Crow era racial inequality, 21st century racism is “increasingly covert, embedded in normal operations of institutions, void of direct racial terminology, and invisible to most whites” (Bonilla-Silva, 2001 p. 48). In fact, when examining experiences within higher education, Students of Color report experiencing hidden, or embedded, forms of racism and overt stereotypes. Examples of these stereotypes include the model minority myth for Asian American students (Assalone & Fann, 2016), the bandido and immigrant/alien stereotype of Latinx students (Owens & Lynch, 2012); and the stereotype that African American students are lazy, and do not value education (Johnson-Ahorlu, 2012).

While fighting both hidden and known stereotypes, Students of Color struggle to find a sense of belonging on predominantly white college campuses, thus leading to inequity via higher rates of attrition than their white peers. Colleges and universities have sought to alleviate this problem through interventions within campus programming, as well as within the college classroom setting. However, without both historical and modern perspectives of Students of Color, it is easier to see differences as deficits and exploit the experiences of “other” for personal or institutional gain. Conversely, studying the impact of AER on minoritized populations via an historical and modern framework leads to asset-based approaches that leave space for critical understanding, multiple perspectives, and equity-based approaches (Crethar, Rivera, & Nash, 2008 & Hernadez, 2016). As investigation into student development, engagement, and retention is positioned within historical and modern frames, blame shifts from the persons and groups experiencing inequity to the systems of power that perpetuate barriers for those living outside the status quo. As the aforementioned summarized history of inequity focused on Black students’ experiences in higher education, know, too that students with different minoritized, and often intersecting identities (i.e., LGBTQIA+ students, differently abled students, students from low socioeconomic backgrounds) face similar inequity (Crethar et. al., 2008).

Stages of Ally Development

Though allyship is sometimes portrayed as a binary, student affairs professionals understand a more complex continuum where deeper examination of self-understanding creates greater knowledge and connection to everyone’s needs. This change in perspective enables a transformative ally development process that can not only lead to increased understanding of self, but also to more effective allyship. Consequently, as professionals engage in more nuanced understandings of self and others via their engagement in AER, changes in ally status are common. In his aspiring social justice ally development model, Edwards’s (2006) espoused the change allies undergo by documenting a shift in perspective from an egocentric or ally-centric stance, to an ally who embraces social justice. In his model described below, the impetus for change falls on allies who must move beyond issues of self-interest and altruism into socially just mindsets that can generate equity.

Self-Interest and Saviorism

Underdeveloped aspiring allies are often self-interested, color-blind people who do not see privilege, and believe in their individual power and ability to protect others (Edwards, 2006). Further, they have difficulty conceptualizing the needs of the target group or issue, and work to maintain the status quo. Similar to saviorism, the underdeveloped ally typically has agent identities, and uses their power to better their position under the guise of serving or helping others. In these instances, tension exists between an underdeveloped ally whose purpose is short-sighted and deficit-laden, and members of target groups who have not asked for help. Similarly, it is not until underdeveloped allies engage in authentic self-exploration that they can expect to transform into a competent ally. Milner (2007) reminds that perspective is within self-identity, and the onus is on the researcher to intentionally and consistently expand cultural work, experiences, and knowledge, while giving voice to historically underrepresented populations, and not amplifying predominately white, male, cisgender, abled, etc. voices. Especially within qualitative research, there is a need to identify and understand the researcher’s position, or reflexivity, in relation to the topic of study (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016; Milner, 2007). Within researchers’ positionality, there is an opportunity to be transparent and authentic about the place from whence the researcher came.

I (Sarah) identify as a white lesbian who grew up in South Louisiana. My experiences in Catholic schools and middle-class environments taught me that I should help others and follow the rules of society. I eventually combined the two and considered my teaching career an opportunity to help others follow the rules of society. Before I embraced my queerness, I did what I could to assimilate to heteronormative traditions and therefore expected others to maintain the status quo no matter their salient identities. When I became a classroom teacher I was surprised that my Black students were not eager to assimilate to my version of whiteness, but instead embraced and celebrated their racial identity. The juxtaposition between my underdeveloped self (as a lesbian and an ally) and my students’ more completely developed Black identity created an opportunity for new perspective via self-understanding. Eventually, I recognized the magnitude of my own biases (i.e., assuming that Black students performed lower academically because of limited parental involvement) and began to challenge them (i.e., racially biased assessments, underfunded schools, and school performance rankings driven by real-estate markets lead to the “achievement gap”). The new perspectives gleaned via ally and self-development are critical professionally and personally as I work through my scholarship, teaching, and service to promote equity and inclusion for all members of society, no matter the constructed rules that oppress.

I (Shanna) self-identify as a white, first-generation female college student who was fortunate to spend the first 18 years of my life growing up in a diverse environment, where my close friends and peers were from various cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds and identities. However, when I transitioned to an undergraduate predominately white institution, I experienced culture shock from witnessing microaggressions and instances of overt racism on campus. I experienced anger and frustration when white peers could not “see” these instances; and outright denied their existence. I also experienced the healing power of conversations on race in a History of African Americans course, led by a Black professor. He empowered the Students of Color in the classroom by affirming their voices and experiences, and taught me the power of listening with humility; and strengthened within me a desire to learn and understand. This enabled me to recognize personal biases, as well as the privileges I had in my own life as a result of my white identity. This professor led the classroom in brutally honest conversations about where our country had been, where it was going, and how we were going to be a part of change in our classroom and on campus.

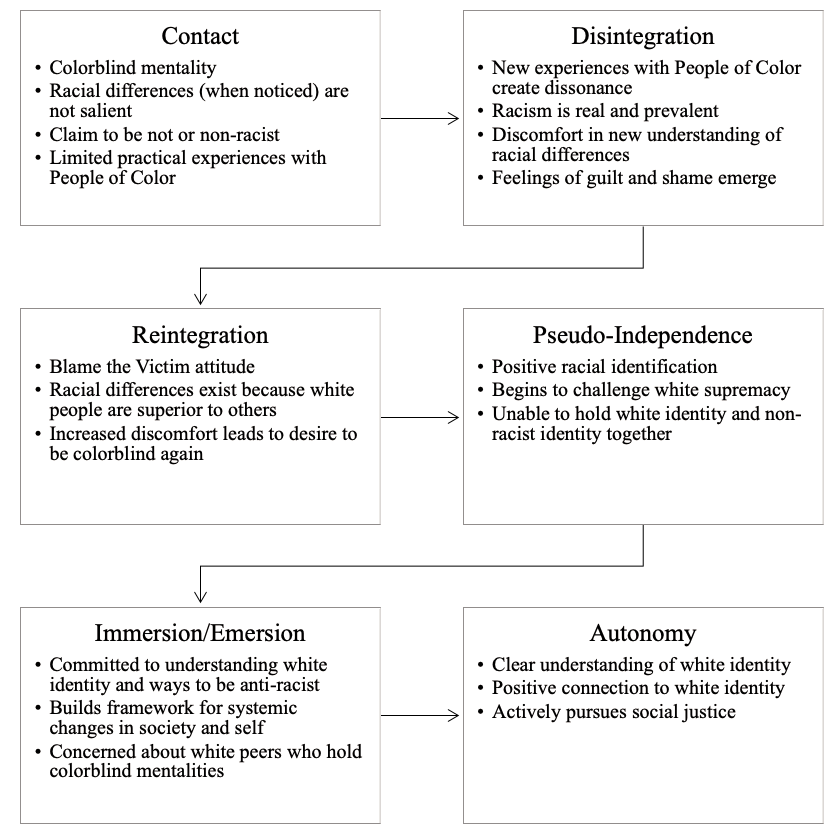

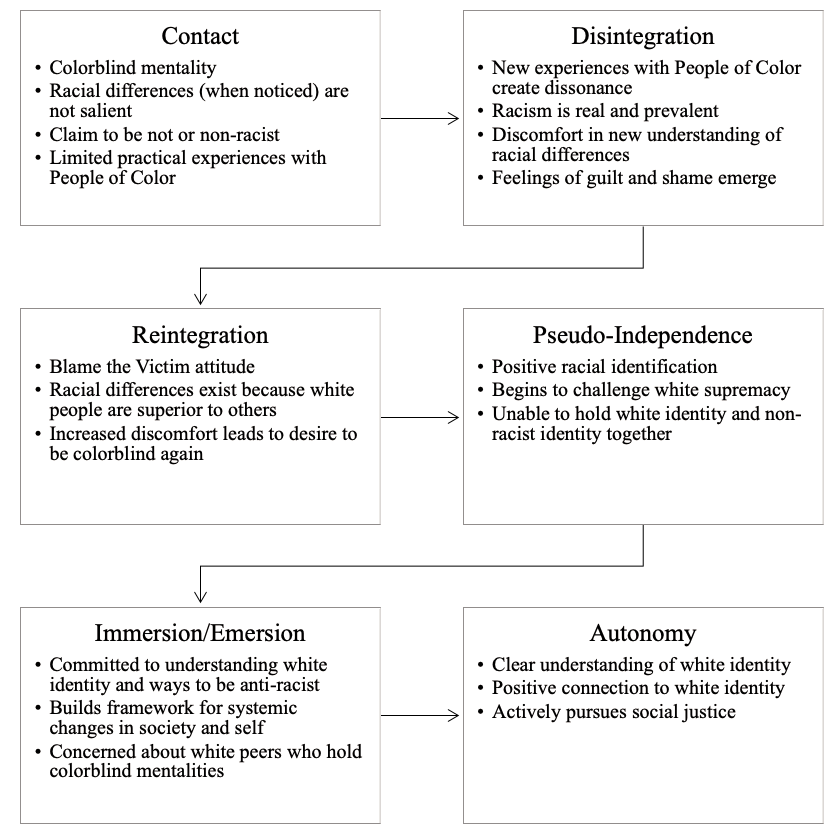

When we do not constantly engage in self-reflection and examination of how our identities influence our research and lens, we are not able to approach our work with authenticity and transparency. If we do not express and exhibit a willingness to constantly learn and converse with those outside of our own identities with thoughtfulness and humility, we will not ever be able to recognize our own biases and privileges, nor will we be able to grow as individuals and researchers. This practice of self-examination and possession of a growth mindset enables us to strive to represent the voices of our participants, rather than us trying to place voices or opinions on others. It also keeps us humble, understanding we are not the saviors; neither are we the victors. Rather, we are servants who are willing to show up, engage, empower, and be led by others in allyship. Helms’ (1990) White Racial Identity Model, below, summarizes the continuum upon which white people move as they develop their anti-racist identity.

Altruism and Allies

Though allies are typically “members of the dominant group working to end the system of oppression that gives them greater privilege and power based upon their social group membership” (Broido, 2000, p.3), Edwards (2006) emphasizes the role of altruism further, but not fully developed allies hold. Before aspiring allies are privilege-cognizant (Baily, 1998) they move along the ally continuum placing themselves and their agent identities at center. Altruistic allies work alongside target groups, trying to empower and help without regard to the larger issue or interconnection of oppressive systems that perpetuate the status quo and agent identity dominance.

To move beyond altruistic allyship it is necessary to make meaning from privileged identities that act as barriers to self and system critique. Though altruistic allies understand that issues move beyond micro-level instances, their goals to empower others are centered in their own agent identities (i.e. conversion therapy for gay and lesbian youth, assimilation of first Americans, etc.) To further develop as an ally it is necessary to make meaning from privileged identities by decentering, reidentifying, and redefining agent identities from an asset perspective (Broido, 2000; Edwards, 2006). Similar to the process necessary for underdeveloped allies, altruistic allies must be ready to accept and reflect upon their own actions that perpetuate the status quo (Edwards, 2006).

When created with equity in mind, student affairs professionals can conduct AER efforts that give voice to traditionally marginalized students. Doing so requires the conductor to embrace their assumptions and biases of self and others and seek information that describes “difference” from an asset perspective. Yosso (2005), for example, decentered traditional concepts of cultural capital within her concept of Community Cultural Wealth (CCW). She redefined wealth from a predominately white perspective, and recentered it based upon the values and perspectives of people of color. In CCW the experiences of people of color are recognized and valued (Yosso, 2005). Scholars have utilized this framework, as well as social reproduction theory (Bordieu, 1973/1986) to examine ways in which students can honor their cultural backgrounds while simultaneously gaining new skills and experiences before, during, and post college (Jayakumar, Vue, & Allen, 2013; Winkle-Wagner & McCoy, 2018). Others have used this framework to examine how students gain access to college, as well as their pathways through college to graduation (Burt & Johnson, 2018; Burt, Williams, & Palmer, 2018).

Allies can expand their cultural understanding in myriad ways, including evidenced based practices that integrate exploration of self and historical injustices (Milner, 2007). Faculty of color are powerful allies not only because they encourage the actions of others, but also because they have the knowledge and skills to break down systemic barriers that hinder progress (Squire, 2017). Allies need to follow rhetoric with action; non-performative are not enough (Ahmed, 2012). When white individuals fall in this category, they are likely to utilize incomplete information, false information, and deflection to perpetuate systemic oppression rather than actively address racist actions or policy (Matias & Newlove, 2017). Allies must actively seek to dismantle these instances of ignorance, racism, and oppression through the utilization of empirical evidence gained through AER (Edwards, 2006). In this way, AER moves altruistic allyship from ideas and purpose statements to activism (Matias & Newlove, 2017; Milner, 2007).

Social Justice and Aspiring Allies

Social justice or aspiring allies have taken opportunities to reflect on their own agent identities and the ways they interact with the status quo and people who hold target identities (Edwards, 2006). By combining their selfishness for creating better spaces for people they know and love with their altruism, aspiring allies believe in empowerment and liberation for everyone (Broido, 2000; Edwards, 2006). As aspiring allies are able to critique accepted norms and admit their own engagement in a system that perpetuates the status quo, they learn to decenter agent identities in order to promote social justice aspirations such as equity, access, participation, and harmony. Aspiring allies have moved along the continuum of ally development, view themselves as part of the problem and solution, and are committed to redefining the interconnected systems of oppression that create layers of inequity (Broido, 2000; Edwards, 2006). For example, empirical findings from previously conducted research (McCoy, Luedke, & Winkle-Wagner, 2017) can be utilized to identify ways in which white faculty members can be allies to Students of Color by avoiding color-evasive (Annamma, Jackson, & Morrison, 2017) racism, and affirming students in all of their identities as they mentor them to and through higher education.

Incorporating Equity, Access, Participation, and Harmony

Acknowledging and recognizing epistemological ignorance and racism forces researchers and administrators to address the influence of systemic inequities on higher education (Matias & Newlove, 2017; Squire, Nicolazzo, & Perez, 2019). Beyond authentic introspection that decenters agent identities, practitioners and scholars can create inclusive AER when they embrace equity, access, participation, and harmony (Lyons et.al., 2013). Utilizing these four aspirations throughout the research process and design creates the necessary dynamic for professionals engaging in AER to situate themselves in spaces where equity and justice are goals and actions.

Instilling equity, or fairness throughout the research process begins with a question of collaboration and continues with the building of a culturally competent research team. Equity, as a theme and aspiration in inclusive AER, continues into the data collection and analysis phases when researchers’ perspectives are asset driven instead of deficit laden. Think about the ways equity is and can be included in the AER process with the following:

- Members of the AER team are culturally competent, racially diverse, and strong, critical thinkers

- Every member can safely express their professional perspective

- Research questions and methods are inclusive, respectful, and ethical

- I have examined my knowledge, biases, and position specific to the topic

Access and participation, though two separate aspirations of socially just AER, are interconnected. As access, a person’s right to “power, information, and opportunity” (Lyons et al., 2013, p. 12), increases throughout the AER process, so too does participation. Participation, the action of engaging, is contingent upon access and built through relationships. Access and participation in the AER process include the following:

- Members of the team share salient identities with participants

- Stakeholders with shared identities are available to code data

- The leader of the AER has built relationships among the community

Harmony, the belief that we are stronger, more creative, and more knowledgeable by working together, is not only the conclusion of AER, but an ideal built through the process of inclusive AER. Since harmony is built via equitable access and participation throughout the process, student affair professionals should consistently engage in the creative acquisition of knowledge about self, while building relationships with various participants. Harmony in AER includes the following:

- Consistent active listening with participants and stakeholders

- Rigorous investigation into potential benefits and negative consequences of policy and other actions

- A collaborative plan for proper closure

Conclusion

Now, more than ever, we have a responsibility to reflect on our own position and power. By developing deeper self-understanding, we acquire the ability to move beyond one dimensional, ahistorical perspectives that limit the assets of our students and participants, while dismantling narratives which support systemic oppression. Like the subtle but intentional movement in allyship development where someone replaces personal altruism for responsibility, professionals conducting AER must act by incorporating equity, access, participation, and harmony in their practices. This is led by anyone committed to self-reflection, critical consciousness, and the ability to learn from their previously held assumptions.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Annamma, S. A., Jackson, D. D., & Morrison, D. (2017). Conceptualizing colorevasiveness: Using dis/ability critical race theory to expand a color-blind racial ideology in education and society. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(2), 147–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248837

Assalone, A. E., & Fann, A. (2016). Understanding the influence of model minority stereotypes on Asian American community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 41(7), 422-435. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2016.1195305

Bailey, A. (1998). Locating traitorous identities: Toward a view of privilege-cognizant White character. Hypatia, 12(3), 27-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01368.x

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2017). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (5th ed.). London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2001). White supremacy and racism within the post-civil rights era. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (ed.), Knowledge, education, and cultural change, pp. 71-112. London: Travistock.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J.G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Broido, E. M. (2000). The development of social justice allies during college: A phenomenological investigation. Journal of College Student Development, 41, 3-18.

Burt, B. A., & Johnson, J. T. (2018). Origins of early STEM interest for Black male graduate students in engineering: A community cultural wealth perspective. School Science and Mathematics, 118, 257-270. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12294

Burt, B. A., Williams, K. L., & Palmer, G. J. (2018). It takes a village: The role of emic and etic adaptive strengths in the persistence of Black men in engineering graduate programs. American Educational Research Journal, 56(1), 39-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218789595

Crethar, H. C., Rivera, E. T., & Nash, S. (2008). In search of common threads: Linking multicultural, feminist, and social justice counseling paradigms. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00509.x

Edwards, K. E. (2006). Aspiring social justice ally identity development: A conceptual model. NASPA Journal, 43(4). 39-60. doi: https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1722

Farrison, W. (1977). Horrison Mann Bond’s “Education for freedom”: A review. CLA Journal, 20(3), 401-409. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/368633

Harper, S. R., Patton, L. D., & Wooden, O. S. (2009). Access and equity for African American students in higher education: A critical race historical analysis of policy efforts. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(4), 389-414. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.0.0052

Heisserer, D. L., & Perette. P. (2002). Advising at-risk students in college and university settings. College Student Journal, 36(1), 69-84.

Helms, J. E. (1990). Black and white racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Greenwood Press.

Hernández, E. (2016). Utilizing critical race theory to examine race/ethnicity, racism, and power in Student Development Theory and Research. Journal of College Student Development 57(2), 168-180. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0020.

Jayakumar, U., Vue, R., & Allen, W. (2013). Pathways to college for young Black Scholars: A community cultural wealth perspective. Harvard Educational Review, 83, 551-579. doi: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.83.4.4k1mq00162433l28

Johnson-Ahorlu, R. N. (2012). The academic opportunity gap: How racism and stereotypes disrupt the education of African American undergraduates. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(5), 633-652. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.645566

Lyons, H. Z., Bike, D. H., Ojeda, L., Johnson, A., Rosales, R., & Flores, L. Y. (2013). Qualitative research as social justice practice with culturally diverse populations. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 5(2), 10-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.33043/jsacp.5.2.10-25

Matias, C. E., & Newlove, C. M. (2017) Better the devil you see, than the one you don’t: Bearing witness to emboldened en-whitening in the Trump-era. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(10), 920–928. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1312590

McCoy, D. L., & Rodricks, D. J. (2015). Critical race theory in higher education: Twenty years of theoretical and research innovations. ASHE Higher Education Report 41(3). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McCoy, D. L., Luedke, C. L., & Winkle-Wagner, R. (2017). Encouraged or “weeded out” in the STEM disciplines: Students’ perspectives on faculty interactions within a predominantly white and a historically Black institution. Journal of College Student Development, 58(5), 657-673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0052

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation, (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Milner IV, H. R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educational researcher, 36(7), 388-400. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×07309471

Owens, J., & Lynch, S. M. (2012). Black and Hispanic immigrants’ resilience against negative-ability racial stereotypes at selective colleges and universities in the United States. Sociology of Education, 85(4), 303-325. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711435856

Squire, D. (2017). The vacuous rhetoric of diversity: How institutional responses to national racial incidences affect faculty of color perceptions of university commitment to diversity. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(8), 728–745. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1350294

Squire, D., Nicolazzo, Z., & Perez, R. J. (2019). Institutional response as non-performative: What university communications (don’t) say about movements toward justice. The Review of Higher Education, 42, 109-133. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0047

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A History of American Higher Education (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Winkle-Wagner, R., & McCoy, D. L. (2018). Feeling like an “alien” or “family”? Comparing students and faculty experiences of diversity in STEM disciplines at a PWI and an HBCU. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 21(5), 593-606. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248835

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006

Figure 1. Summary of Helms’ (1990) White Racial Identity Development