written by: Dr. Shannon Dean-Scott, Alicia Stites, Mohammad Khan

Abstract

More and more people in the U.S. are identifying as Multiracial; colleges and universities are also seeing this increase in Multiracial students. Through campus involvement, these students often develop their understanding of identity. Our qualitative study examines eight students’ experiences to understand the development of their Multiracial identity through campus involvement. We offer findings, analysis, and recommendations to build more inclusive environments that foster intentional involvement opportunities and significant racial identity development for Multiracial students.

Exploring the Role of Involvement in Cultivating a Multiracial Identity

As the number of individuals in the United States who identify as Multiracial rises, colleges and universities (Hanson, 2024) also see an increase in Multiracial students (Mitchell & Warren, 2022). While many factors contribute to a Multiracial student’s identity development, environments continue to serve as critical influences on how these students navigate college campuses (Giebel, 2023). We build upon Renn’s (2000, 2003) use of Bronfrenbrenner’s (1993) Model of Developmental Ecology by exploring the unique context of involvement at a Hispanic Serving Institution and the influence on Multiracial identity development and engagement.

Based on findings from a qualitative study with eight Multiracial students, we highlight the reciprocal relationship between the campus co-curricular experience and identity development. We outline insights from involved students about their own perception of their racial identity, their interactions with monoracial peers, and their transformation about understanding race. We also discuss how racial singularities are a driving institutional and social force that plays a critical role in interpersonal relationships and the larger campus culture for Multiracial students. These racial singularities are systemic and pervasive yet generally go unaddressed by student affairs professionals often due to a lack of resources (Mitchell & Warren, 2022). We close the article by offering recommendations for disrupting racial singularities in campus spaces and building more inclusive environments that foster intentional involvement opportunities and more significant racial identity development for Multiracial students.

Historical and Theoretical Context

In order to understand the history of Multiracial college students and their identity development, one must understand the past and current landscapes related to Multiracial individuals. In 2000, the U.S. census added the ability to select more than one racial identity. Of the 281.4 million people who filled out the census, 6.8 million (2.4%) identified as more than one race (U.S. Census, 2000). During the 2010 census, there was an increase in those who identified as Multiracial from 6.8 million to 8.9 million, 41% of whom were under 18 years of age (US Census, 2010). Many of those individuals are now attending college. As of 2023, 4.3% of the college student population identified as Multiracial and among this group, college attendance has increased by 133% since 2010 (Hanson, 2024). This is important to note when considering what we know about Multiracial students in terms of developmental theory and involvement. The experiences of Multiracial students are under-researched. Our study helps address this knowledge gap.

Current Multiracial identity development theories are built upon other monoracial identity development models such as Cross (1971) and Morten and Atkinson (1983), some of the first identity theories that did not center whiteness. These theories were foundational for Poston (1990) who created models of biracial identity development and Root (1996) who discussed Multiracial identity development; both focused on the healthy development of a racial identity and acknowledged Multiraciality as important. Building on these theories, Renn (2003) created a Multiracial identity development theory that included the psychological, sociological, and ecological needs for college students from mixed racial backgrounds.

Renn (2003) used Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model to examine Multiracial college student experiences. She considered the holistic influences of the individual (person), the environment (process), the immediate surrounding (context), and changes in development (time). Renn’s (2003) theory highlighted the importance of peer culture and belonging as critically essential components of developing their Multiracial identities. These include public spaces, and private spaces for students to reflect and discuss their identities with others (Renn, 2008). These reflective conversations occur in contexts including clubs, organizations, and other involvement opportunities (Renn, 2003). Much work is still needed to understand the complexities and development of Multiracial college students.

Challenges with Current Theories

One challenge with the current set of Multiracial theories is that previous literature focuses on Multiracial categorically and not individual identity groups. Although some Multiracial individuals prefer this designation and feel they have more in common with their Multiracial peers (Gardner, 2014; Hentz, 2019), these theories do not capture the various experiences of different Multiracial students based on their multiple monoracial backgrounds. It would be challenging to capture every Multiracial individual’s unique racial experiences, and yet it is a gap in our understanding of how Multiracial students navigate college environments and develop their identities. Our study responds to the need for better understanding the Multiracial student experience.

Importance of Involvement for Racial Identity Development

Theories enable some understanding, however, never fully encompass lived experiences of students, in this context for Multiracial identity development. Further, there is literature about how students develop in college, in their racial identities, and how racial identity impacts involvement (Willis, 2017). Involvement increases GPA, satisfaction, and graduation rates (Conefrey, 2021), but can be impacted by their racial identity (Hentz, 2019; Mahoney, 2016; Willis, 2017). However, more research is needed to better understand how involvement impacts identity development.

We use Astin’s (1999) definition to understand how students develop Multiracial identity through college involvement. Astin (1999) defined involvement as the amount of physical and psychological energy students devote to the academic experience including academics, co-curriculars, leadership, and other involvement. This definition allows us to consider various involvement experiences and nuance the psychological component of involvement.

The discussion about whether leaders are born or made, whether one is a leader or a follower, and the definitional differences between leaders and managers are just some ongoing discussions and theories within leadership education (Northouse, 2019). Much leadership theory debate stems from one’s paradigm about truth and identity. Involvement theories and leadership theories are closely connected regarding benefits to students. Through sustained and encouraged involvement and various forms of leadership many students find themselves.

In order to critically examine theories of identity development, involvement, or leadership, one should consider metacognition, critical self-reflection, social perspective-taking, dialectical thinking, and critical hope (Dugan, 2017). Metacognition refers to how we think about theories, whereas critical self-reflection suggests looking at yourself, your positionality, and engaging in self-exploration (Dugan, 2017). Social perspective taking is the ability to adopt another person’s point of view; dialectical thinking implies the ability to hold conflicting or contradictory concepts together (Dugan et al., 2014). Finally, critical hope is the ability to realistically appraise a situation while envisioning a better future (Bishundat et al., 2018). Each of these concepts relies on the ability of the individual to know themselves, their identities, their struggles, their privilege, and to be able to make meaning of their experiences to see other points of view and envision something better.

Taking a critical perspective is not simply knowing the content and the theory, it is about diversifying content and theories. Research recognizes the importance of social identity development within involvement and leadership opportunities (Mahoney, 2016). Further, researchers have looked critically at the role of racial identity plays in involvement (Gardner, 2014; Willis, 2017) and how involvement fosters racial awareness and support, particularly for Multiracial students (Gardner, 2014). Recognizing and valuing the importance of understanding yourself, while also understanding others is imperative for continued development (Mahoney, 2016). Students make meaning of their social identities through relationship with others via involvement which is particularly beneficial for Multiracial students on campus. Our study sought to identify the ways Multiracial students better understood their own racial identity through and because of their college involvement.

Methodology

To advance the conversation on Multiraciality and student engagement, our study examined Multiracial student experiences in co-curricular activities on an HSI campus. We focused on upper-division students (junior and seniors) active in organizations, groups, or programs. The study focused on the environment and peer relationships with peers to assess the development of the racial identity of Multiracial students through co-curricular involvement. Our study centered how Multiracial students viewed themselves on campus, in interpersonal relationships, and how the environment shaped their view of race and Multiracial identity.

This study used a qualitative phenomenological approach. Qualitative research allows for rich descriptions and an in-depth understanding of a particular time, setting, and experience (Creswell, 2014). Rather than predict phenomena, qualitative inquiry allowed us to understand the intricacies of racial identity development and the role and/or influences of involvement and the environment in this development. Identifying participants as the teachers, phenomenological research provided participants space to share and interpret their experiences (Creswell, 2014)in order to identify common themes across the experiences of Multiracial students.

We conducted our study at a large public state institution in the southern United States with a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) designation. Determined by the U.S. Department of Education, the HSI designation is granted to institutions with more than 25% of their student population identifying as “Hispanic” (White House Hispanic Prosperity Initiative, n.d.). At the time of the study, student demographics at the institution reflected that about 4% of the student population identified as biracial or Multiracial. The study included eight Multiracial student leaders, seven of whom identified as women and one who identified as a man. We tailored our selection criteria to include only juniors and seniors, students involved in any form of co-curricular activities, and students who self-identified as Multiracial. We worked with Institutional Research to email junior and senior students who identified as two or more racial or ethnic identities on their enrollment documents. We intentionally sought juniors and seniors intending to interview students who would have had a broader range of involvement experiences.

We explored students’ perceptions of their racial identity, their experiences in co-curricular activities, and their overall engagement with the campus environment through one-on-one interviews that lasted approximately 60 minutes. We utilized a semi-structured interviews, asking about their pre-collegiate experiences and how the leadership opportunities they took part in impacted the formation of their social and leadership identities.

We used a three-cycle data analysis process (Saldana, 2009). The first step was transcribing interviews. Next, we individually reviewed and coded each transcript, utilizing NVivo to code and identify essential and salient ideas. We then collectively generated and compiled the codebook. Each code was revisited and sometimes re-coded to craft new co-generated codes that determined the larger categories and themes in the study. In order to ensure trustworthiness, we kept a careful audit trail of all the records and details of the data analysis process. Additionally, we triangulated the data by utilizing multiple researchers and cross validation techniques.

Positionalities

Each of us came to this research from our own racial perspectives and from a variety of involvement opportunities both in college and within our careers. We believe it is important in understanding our research, to better understand a bit about the paradigms and experiences we bring to this study.

For Mohammad: As a Desi Muslim cisgender man, I value the impact involvement can have on community building and identity development. Being an involved student leader in college contributed to my understanding of the intricate dynamics of cultural assimilation and preservation, deepening my understanding of what it means to belong. While I do not identify as Multiracial, my bicultural upbringing informs my perspective on the nuances of Multiraciality. I understand the vital importance of amplifying the stories and experiences of marginalized students to better inform, analyze, and act for change on college campuses.

For Alicia: My experience as a biracial, cisgender woman navigating college impacted my motivation to explore and research multiracial identity and involvement in higher education. My own experiences are a narrow scope on Multiraciality and I strive to focus on each unique experience to improve my understanding multiracial scholarship. I currently serve as a co-chair on the Multiracial Transracial Adoptees Network within ACPA that focuses on building community and furthering scholarship.

For Shannon: I am a White, cisgender woman who grew up in a very racially diverse part of California and spent my first year of college in Idaho where the lack of racial diversity shocked me. My first-year experiences initially lead me to transfer schools and ultimately guided many of my career and research choices. I currently serve as a faculty member in a student affairs preparation program where we intentionally engage in discussions around racial justice and inequities.

We began working on the foundations of this research when taking Shannon’s course on Research Methods in Student Affairs. Over the course of the next year, we combined our individual research interests – on Multiraciality, involvement, and environment – to execute this study. We each contributed our unique insights and leveraged our positionalities to enrich the research.

Limitations of the Methodology

Although this study offers valuable insight into how Multiracial students understand their racial identity due to their campus involvement, the study did have some limitations. We reached out to various campus involvement offices and leadership professionals to recruit participants. Yet our participants primarily identified as women which limits our findings. Further, our study focused on a specific group of upper-division Multiracial students within a specific HSI campus environment. There are many ways in which our findings are relevant to other contexts, yet it is important to note that Multiracial students elsewhere may have different experiences.

Findings

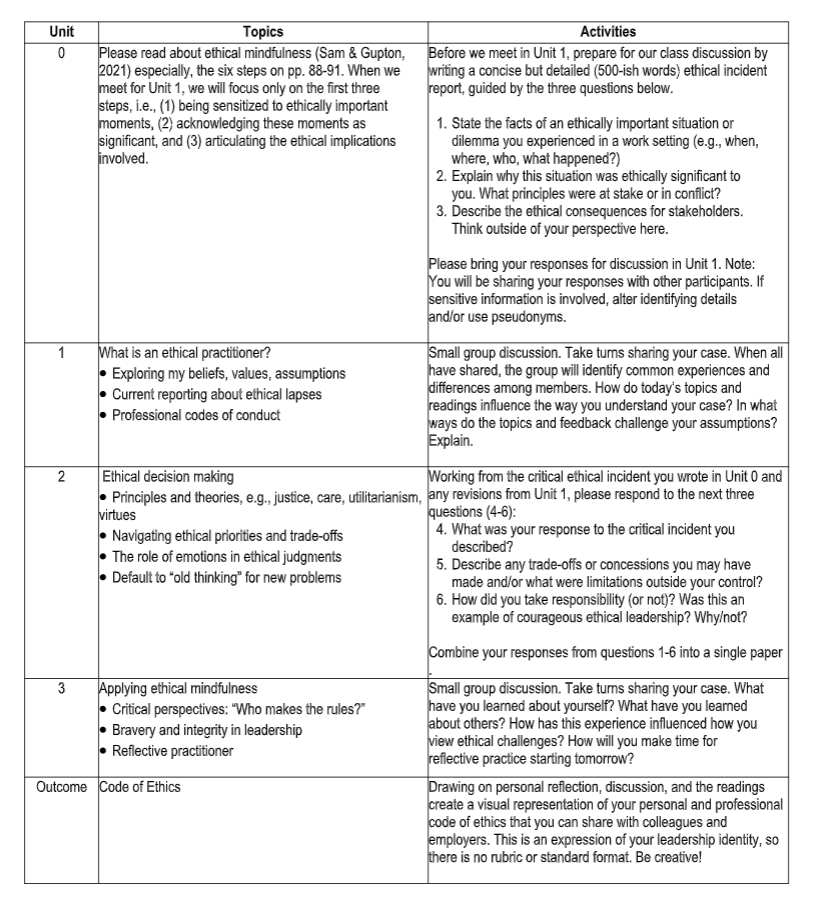

The three key themes from our study included: (a) self-perception of Multiraciality; (b) societal understanding of Multiracial identity; and (c) ideological views of racial identity. The majority of the students interviewed entered the university with a conscious understanding of their racial identity. We found that students’ interpretation of self, society’s comprehension of Multiracial identity, and how a Multiracial student’s experience shaped their views and actions regarding race were shared experiences for students in our study. In this section, we describe and provide examples of each theme. Additionally, instead of a separate discussion section, we include in our analysis implications and suggestions for student affairs professionals to improve the experience and environments for Multiracial students on campus to excel in their leadership endeavors.

Self-Perception of Multiracial Identity

The students’ perception of their Multiraciality and how others perceive it shapes how they navigated co-curricular involvement. People unfamiliar to them would often confront them about their appearance within the group or organization. Whether the purpose for questioning a Multiracial person’s physical appearance is out of curiosity or the need to compartmentalize races, the exchange forced Multiracial people to explain themselves.

One participant, Rebecca, recalled accounts affecting her perception of her racial identity,

Growing up, I used to be like, ‘I’m Hispanic’ and everyone was like, no, you look very White…so I don’t really fit into a certain category. Then I am just Multiracial because I am not specifically a part of this group or this group or this group. I’m a mixture of all.

Rebecca set herself apart from racial identity groups by choosing to identify as Multiracial, which to her does not connect with any particular group. She did not seem to find acceptance or belonging within these groups as a shared singular racial identity.

Multiracial Identity and Language

Aside from physical appearance, knowledge of a heritage language impacted how Multiracial students qualified their identities. Hermine, when deciding to join a multicultural sorority at the start of her college career, stated, “I’m only half Hispanic so sometimes I see Multiracial [people] and they’re speaking Spanish. I’m not sure if I would fully fit into that category.” Hermine was deterred from joining an organization because her language abilities different from others in the group.

On the other hand, Multiracial individuals may use their language abilities to fit into groups and prove relatability. Rebecca shared, “In a social [setting] to fit in the groups, you know? I would definitely bring up more of my Latina background… And mention some words in Spanish.” Rebecca emphasized aspects of her identity to have a sense of belonging often using her bilingual abilities to fit in. Rebecca seemed very aware that language and sharing personal experiences related to her Latina background and strengthened the connection with others in the group.

Multiracial Students Frustrations

Students expressed frustration with monoracial people’s lack of understanding and knowledge as a source for the challenges they face navigating their Multiracial identity. Raymond explained how identity confusion stems from monoracial people because, “They don’t have a lot of knowledge on how to approach a situation when someone looks a little different.” He further explained a situation when he and his sister moved to the suburbs, “We didn’t blend in with the white kids… we looked more like their skin tone but our hair was different and there were always fights with [white] people over our racial identity”. Multiracial people often grow up trying to develop the best explanation of identity for themselves and others.

Sarah expressed confidently identifying as Multiracial growing up but also faced challenges from others, “Have to be honest, I’ve never really struggled with accepting being biracial, but I’ve just had a hard time with other people just trying to accept me.” Both students expressed how identity expression can be difficult because others are not knowledgeable about their identity.

Students described a precarious peer culture that led them to question their identity or highlight aspects of themselves to enter peer groups. Sandra noted, “People just sort of ask me ‘What are you?’ I just get confused because I’m like, ‘Are you meaning the city I last lived in?’ I feel like with that question I don’t really understand their meaning.” Marian said, “I don’t really feel comfortable showing up there [monoracial organization] and kind of feel like I’m taking up space as someone who is very white passing… People have said ‘You’re too white for this, like you’re not actually Mexican.’” Sarah added, “On campus people just always assume that I’m Hispanic and people will say, ‘Wow you look like a Hispanic, like your facial structure’ and I have to reiterate I’m Multiracial.” Alongside interactions with peers, students expressed discomfort trying to enter public spaces and organizations on college campuses. Multiracial students need interactions and spaces that allow them to be authentic, self-explore, and develop their identity.

Perceived Societal Identification of Multiracial Identity

Multiracial individuals have to navigate their various identities in different spaces. Sometimes this means representing one identity over another in a certain context or recognizing how phenotypical representation of their race plays a role in the perception of identity. Other times, others racially categorize them with or without their knowledge. Many of our participants discussed how their first understandings of how people perceived them racially came from family.

Natalie shared how being half Tongan and half white would show up differently based on which side of the family she was with. Natalie shared, “When I am with my Tongan side, I just forget about that other side and I am just Tongan. But when I am with my White family, I stand out more because I don’t look anything like my cousins.” For Natalie, her family reinforced the similarities in racial identities but sometimes neglected her Multiracial identities.

Similarly, Sarah said,

“My dad is Black and my mom is White and our background is French and Hispanic…

Growing up with two different sides has always been a part of my life, and you can’t

choose a side, people want you to choose… It’s hard for other people to accept.”

Sarah shared that even her family created pressures to choose a monoracial identity over her biracial identity. Participants started to recognize early in life the perception others had of their Multiracial identities and participants’ desire or need to placate to others by privileging one portion of their racial identity in certain settings.

Others’ need for students to prioritize one part of their identity over others became more pronounced in college. Participants discussed how during college they had to navigate others’ perceptions and their own emotions related to managing multiple racial identities. Marian spoke about a campus club stating, “I’ve always felt like I don’t really fit into one place. As someone who is White passing, I’ve never felt comfortable joining [racial identity based] clubs.” Sarah tried to join the Hispanic Business Student Association (HBSA) and shared,

When I went [to the HBSA], I didn’t like the vibe I was getting because of how I looked… I also tried to join another organization for Latina women and when I went with my friend (who looked more Latina than I did), the president [of the organization] was only talking with her.

Participants often mentioned the struggle to fit in based on their perceived identities. Additionally, some participants also discussed difficulty fitting in based on their Multiracial identities. They were told they looked too much like one racial identity and not enough of another.

Ideological Views of Racial Identity

Most of the participants in the study shared how their worldview evolved, both as it relates to society as well as their place in it. Students in our study were in the latter part of their undergraduate career. The culmination of their experiences as a Multiracial individual growing up and engaged on a higher education campus, particularly a Hispanic Serving Institution, shaped their perceptions of their racial identity in society. Their views, beliefs, or ideologies shaped how they engaged with monoracial people and how they navigated their experiences within their Multiracial identity. For example, Sandra sought understanding and for monoracial peers and staff to be more open to Multiracial individuals.

I just wish that people can be more knowledgeable and like want to learn more about it [my multiracial identity] cause you know mostly or people that I know that are monoracial don’t want to learn, don’t want to know. And so, I feel it’s their job as well to educate themselves however for us biracial or Multiracial and to provide them less- not lessons, but just teach them as well “Hey, that’s not okay.”

In addition to Sandra wanting monoracial people to be open to learning about Multiracial experiences, she wanted Multiracial people to speak up for themselves more. Sandra’s thoughts were mirrored by almost all participants in terms of a need for Multiracial student self-advocacy. Participants shared how they assessed the world around them and the various spaces in which they navigated and advocated for themselves.

Natalie said she has come to terms with how she perceives her identity and expresses herself. She reflected on her experiences, saying, “Growing up was a bit of a struggle. Once you’re old enough to realize, it is like trying to find this balance. And it took me a long time to realize it [my Multiracial identity] doesn’t need to be divided down the middle. It’s just both.”

Multiracial people are often viewed as fractions of racial identities within one person, which is dehumanizing and operates within a deficit mindset. For students in our study, the majority had experiences where peers or family devalued their multiracial identities and instead wanted them to choose between their racial identities. Many participants shared situations where they felt not enough of one racial identity in order to be a member in that group. Instead of dividing themselves, many of our participants found solace in accepting their racial identities wholly. Natalie summed this acceptance up saying, “Being multiracial doesn’t mean a subtraction or some kind of fraction… it is wholeheartedly both”.

Discussion

Although the previous literature on Multiracial student identity development provides a foundation for understanding racial identity, this study expands the literature by looking at this development through an involvement lens. Much is known about the benefits, generally, of involvement (Conefrey, 2021), and yet this study identified three ways our participants developed their Multiracial identity through campus involvement. The three themes (self-perception of Multiraciality, societal understanding of Multiracial identity, and ideological views of racial identity) all have parallels to previous literature. Our findings also have implications for practitioners and researchers as we consider how to best support the development of Multiracial students.

Involvement in organizational and collaborative spaces with peers provides Multiracial students the opportunity to find community and share similar experiences. These socio-cultural conversations foster personal identity development and provide affinity and language with which to navigate Multiraciality in the academy. These experiences are central to college students’ social identity development and even more critical as Multiracial students seek to identify who they are (Renn, 2008). Renn (2008) highlighted the importance of peer culture and its influence in various areas on- and off-campus. Students enter spaces (microsystems) that directly and indirectly shape them. For many of the participants, their physical appearance shaped the interactions they had with other students. Thus, it is imperative for Multiracial students to find a sense of belonging in physical spaces that allow them to connect with others who look like them and hold shared identities.

Multiracial students also discussed how peers impacted participants’ feelings associated with their Multiracial identity. Through peer culture students may be pressured to express aspects of a shared identity to feel accepted (Renn, 2020). For many people of color and Multiracial individuals, racial socialization comes early in life through parental figures or caretakers (Gardner, 2014). Yet, college is a time of exploration and development, and many Multiracial students feel they must choose singular identities over their preference for blended identities (Gardner, 2014). The peer interactions and pre-collegiate experiences inform the students’ context and define the nature of their Multiracial identity. The exposure of Multiracial students to multiple familial and peer contexts provides a forum for dialogue and exposure that is not commonly seen in monoracial experiences.

When trying to better understand the perceptions from others based on Multiracial identities, it is important to recognize the impact peers have on a Multiracial individual understanding and embracing their identities (Renn, 2008). Racial identity is not only constructed within social relationships, but development is fostered through these constructed social environments. Multiracial students will thrive and gain better understanding of their racial identity if they are involved in environments that foster and accept all facets of their racial identities (Gardner, 2014). The burden of advocacy becomes a challenge when spaces are designed (intentionally or unintentionally) to create barriers or limit full involvement in various student experiences. Student affairs professionals have the ability to positively impact student leaders and to foster spaces on campus where Multiracial students can show up as their whole racial selves.

Implications for Practice

As student affairs professionals, we must educate monoracial individuals on the complexities of racial constructs with an intentional focus on Multiracial students. This means educating students and colleagues about the experiences of Multiracial students and challenging traditional notions of identity. This education and challenge can come in various ways, such as allowing students to identify with multiple races on forms or creating alternatives for individuals to self-identify as Multiracial. By enabling people to identify as Multiracial, we begin to shift the narrative away from the specific multiple singular racial identities that people hold and begin to discuss identity more comprehensively actively including Multiracial persons.

Student affairs administrators must commit to being intentional about Multiracial student empowerment, particularly in building leadership capacity. The Multiracial student’s journey of understanding self and navigating monoracial spaces provides ample opportunity to cultivate skills and explore personal beliefs and values. We must also evaluate leadership systems and practices on our college campuses, including affinity-based student organizations, student centers, services, and events.

Student affairs professionals can support Multiracial students by normalizing Multiracial identity in monoracially dominated spaces. Students can be influenced by the environment and culture of the people around them thus impacting their ability to live authentically with one’s racial identity. Practitioners can facilitate this culture by disrupting the normalized monoracial dynamics through conversations and institutional forms. Reflecting on race as a social construct provides an opportunity for both monoracial and Multiracial students to engage and develop an understanding of varying racial identities.

Throughout their student involvement journeys, Multiracial students reflected on their racial identity and navigated multiple contexts that inform their perspectives on Multiraciality and their relationships with monoracial peers. Our study identified the ways that leadership and involvement opportunities shaped students’ racial understanding of themselves, how others perceived their race, and ultimately their ideological standpoints in terms of understanding race. Through experience and research-based practice, higher education leaders can transform the leadership capacity of Multiracial students with a focus on creating intentional spaces of belonging.

Implications for Future Research

Although this study provides some insight into the experiences and development of Multiracial students in the context of their involvement, more research is needed to truly understand Multriacial students’ identity development. Further research could explore how various types of involvement differentiate how students’ Multiracial identity develops. While this study takes a broader perspective of involvement, additional investigation is required to nuance student organizational involvement versus academic involvement, or whether involvement spaces must specifically address race to foster belonging. This could lead to a greater understanding of how involvement, and particularly certain types of involvement and leadership opportunities, help students develop their racial identities.

In addition to different types of involvement, it is also important to obtain a larger more diverse sample size in terms of gender identity. A larger sample is needed to allow for the richness of students’ experiences to be explored and determine how these experiences are influenced by other aspects of students’ identity. This study does not address the role of intersecting identities, particularly as it relates to gender and Multiraciality. A larger more diverse sampling would be beneficial for a qualitative study or allow for a quantitative study. In a quantitative study, researchers could explore the relationships between types of involvement in college and Multiracial students’ identity development opportunities, as well as feelings of belonging across various intersecting identities. Additional qualitative studies could emerge from this quantitative assessment that investigate these results using an intersectional framework. As student diversity continues to increase on college campuses, understanding how these identities intersect and influence each other will be crucial in advancing student development and sense of belonging.

Further, while the population of Multiracial individuals grows in the United States, consideration for each growing generation should also be taken into account. The Multiracial population is expected to triple in size by the 2060 census. Thus, there will likely be an emerging population of Multiracial students who are raised by one or more Multiracial parents, which raises questions about the formative experiences of these students, when compared to students who may have monoracial parents. Future researchers need to be cognizant of how parental and guardian influences shape identity development for Multiracial individuals. This shift away from a monoracial lens as the Multiracial populations increase is an important consideration in identity development and should be researched as generational shifts happen. It would be incredible to determine what impacts the development of Multiracial college students and how a more visible populations affects monoracial peers’ perception on Multiracial identity.

Conclusion

While this article provides insight into the involvement experiences of Multiracial college students and their perspectives on racial identity, there is still much work to be done to create better environments (physical and metaphysical) for students to engage with each other around racial development.

As higher education professionals continue to disrupt dominant narratives around involvement and racial identity, they must pay special attention to the unique experiences of Multiracial students. Whether navigating positional or organization roles, engaging in service activities, or taking part in other leadership development practices, how we support Multiracial students must be intentional and must attend to their unique needs. Our practices should begin with an openness to learn and receive, provide space for identity exploration and empowerment, and reimagine the philosophies and traditions of leadership and involvement. In supporting Multiracial students and their desired co-curricular involvement on campus, professionals must stay informed on current trends, issues, and barriers related to Multiracial student involvement and seek opportunities for advocacy and activism. These practices demand institutional financial and intellectual resources and ultimately allow for creating more equitable spaces for Multiracial students.

References

Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 40(1), 518-529.

Bishundat, D., Phillip, D. V., & Gore, W. (2018). Cultivating critical hope: The too often forgotten dimension of critical leadership development. In J. Dugan (Ed.). Integrating critical perspectives into leadership development. (New Directions for Student Leadership, 159, 91-102).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Conefrey, T. (2021). Supporting first-generation students’ adjustment to college with high-impact practices. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 23(1), 139–160.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publication, Inc.

Dugan, J. P. (2017). Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives. Wiley & Sons.

Dugan, J. P., Bohle, C. W., Woelker, L. R., & Cooney, M. A. (2014). The role of social perspective-taking in developing students’ leadership capacities. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 51(1), 1–15.

Dugan, J. P., Kodama, C., Correia, B., & Associates. (2013). Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership insight report: Leadership program delivery. National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2011). Leadership theories. In S. R. Komives, J. P. Dugan, J. E. Owen, C. Slack, & W. Wagner (Eds.), The handbook for student leadership development (2nd ed., pp. 35–57). Jossey-Bass.

Giebel, S. (2023). “As diverse as possible”: How universities compromise Multiracial identities. Sociology of Education, 96(1), 1-79.

Harris, J. C., & BrckaLorenz, A. (2017). Black, white, and biracial students’ engagement at differing institutional types. Journal of College Student Development, 58(5), 783-789.

Harris, J. C., BrckaLorenz, A., & Laird, T. F. N. (2018). Engaging in the margins: Exploring differences in biracial students’ engagement by racial heritage. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(2), 137-154.

Hanson, M. (2024, January 10). College enrollment & student demographic statistics. EducationData.org. https://educationdata.org/college-enrollment-statistics.

Hentz, A. N. (2019). Using grounded theory to explain the impact of appearance on Multiracial identity development. University of Maryland Dissertation.

Komives, S. R., Lucas, N. J. & McMahon, T. R (2013). The Relational Leadership Model. In Exploring leadership: For college students who want to make a difference (3rd ed.) (pp. 93-145). Jossey-Bass.

Mahoney, A. D. (2016). Culturally responsive integrative learning environments: A critical displacement approach, In K. L Guthrie, L. Osteen, & T. B. Jones. (Eds.), Developing Culturally Relevant Leadership Learning. (New Directions for Student Leadership, 152, pp. 47-59). Jossey-Bass.

Malaney, V. K., & Danowski, A. K. (2015). Mixed foundations: Supporting and empowering Multiracial student organizations. Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity, 1(2), 55-85.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A.M. (2004). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Mitchell, S., & Warren, E. (2022). Educational trajectories and outcomes of Multiracial college students. Social Sciences, 11(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030101

Morten, G., & Atkinson, D. R. (1983). Minority identity development and preference for counselor race. Journal of Negro Education, 52(2), 156-161.

Northouse, P.G. (2019). Leadership: Theory and practice. Sage.

Ostick, D. T., & Wall, V. A. (2011). Considerations for cultural and social identity dimensions. In S. R. Komives, J. P. Dugan, J. E. Owen, C. Slack, & W. Wagner (Eds.), The handbook for student leadership development (2nd ed., pp. 339-368). Jossey-Bass.

Ozaki, C. C., & Johnston, M. (2008). The space in between: Issues for Multiracial student organizations and advising. In K. A. Renn & P. Shang (Eds.), Special issue: Biracial and Multiracial students (New Directions for Student Services, 123, pp. 53–61). Jossey-Bass.

Poston, W. S. (1990). The biracial identity development model: A needed addition. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69(2), 152-155

Renn, K. (2020). The Influence of Peer Culture on Identity Development in College Students. Journal of College and Character, 21(4), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2020.1822879

Renn, K. A. (2008). Research on biracial and Multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis. In M.D. Coomes and R. Debard (Eds.), Serving the millennial generation (New Directions for Student Services, 123, pp. 13-21). Jossey-Bass.

Renn, K. A. (2003). Understanding the identities of mixed-race college students through a developmental ecology lens. Journal of College Student Development, 44(3), 383-403.

Renn, K.A. (2002). Patterns of situational identity among biracial and Multiracial college students. In C. Turner, A. Lising-Antonio, M. Garcia, B. Laden, A. Nora, & C. Presley (Eds.), Racial and ethnic diversity in higher education (pp. 322-335). Pearson Custom Publishing

Root, M. P. P. (1996). The Multiracial experience: Racial borders as the new frontier. Sage.

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications.

Shankman, M. L., Allen, S. J., & Haber-Curran, P. (2015). Emotionally intelligent leadership: A Guide for Students (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

White House Hispanic Prosperity Initiative. (n.d.) Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs). U.S. Department of Education.

Willis, J. C. (2017). Racial identity amongst Black undergraduate females who attend predominately White institutions and how it is linked to their college student involvement. (Publication No. 10605873) [Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

About the Authors

Dr. Shannon Dean-Scott (she/her) is an associate professor in Student Affairs in Higher Education (SAHE) at Texas State University. Dr. Dean-Scott teaches courses in student development theory, assessment, research methods, and internship experiences in higher education. Dr. Dean-Scott’s current research focuses on multicultural consciousness of undergraduate students, assessment practices, and teaching pedagogies.

Alicia Stites (she/her) serves as a Senior Program Coordinator for the Foundation Scholars Program at The University of Texas at Austin. Alicia Stites manages a cohort of mentors supporting first-year students in a yearlong mentorship program focused on student success, academic excellence, and holistic student development. Current research interests include Multiracial identity development and first-year student success.

Mohammad Khan (he/him) is an assistant director for global programs and experiential learning at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. In this role, Mohammad oversees the operations and marketing of global business courses and domestic experiential learning opportunities for MBA students. Previously, Mohammad held roles in leadership and civic engagement functional areas at the University of Houston-Clear Lake and Texas State University, which prompted his research interests in identity, leadership development, and student engagement.