written by: Jonathan J. O’Brien, Ed.D.

There is never enough time or information to make difficult decisions, particularly when we are caught in ethically challenging situations attempting to balance stakeholder needs with policies and community standards. When overwhelmed by difficult choices, we grasp for solutions. Afterward, as we move on to the next problem, opportunities for reflection on our practices fall by the wayside. However, reflection is vital for personal, professional, and ethical growth. The ACPA/NASPA (2015) competencies urge practitioners not only to acknowledge the importance of reflection, but to proactively build reflective practices into regular workflows. Reflection is an essential foundation for translating insights into concrete actions.

Institutional environments also shape the ethical situations practitioners face and the responses available to them. When policies, structures, and norms conflict with practitioners’ personal values, tension arises, forcing difficult tradeoffs. For example, the recent legislative assault on DEI at institutions around the country has threatened the safety of students and the careers of practitioners (Charles, 2024). Further, when we witness unethical behavior, such as the tragic consequences of harassment and bullying (Hollis, 2024) the experience can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and a loss of purpose. Although there are ethical decision-making models and trusted mentors who can provide guidance when evaluating various courses of action, facing ethical challenges ultimately requires us to strike a balance among competing priorities – namely ethical principles, emotional triggers, and personal values like integrity and self-respect. This takes courage, an important aspect of our work that is often overlooked.

Student affairs practitioners can experience toxic situations in which core values like care, advocacy, and idealism are thwarted by chaotic, authoritarian, or corrupt institutional cultures and the toxic interpersonal relationships cultivated within them. Experiences can range from mild to severe. For example, a housing professional who witnesses a colleague being bullied may experience moral suffering, as might a dean who must stay silent due to confidentiality laws while facing public scorn for perpetuating systemic oppression. Faced with constraints, practitioners are torn between upholding their personal and professional values and surrendering to an institutional culture that undermines their moral purpose.

In this article I discuss ethical mindfulness as a means for professionals and graduate students to work through ethically challenging situations. After describing benefits of mindfulness, I apply a framework to my experience to demonstrate how mindfulness can build self-awareness, reflexivity, and courage in ethically challenging situations. Next, I suggest how I have used it with graduate students to help them navigate the challenges they experience in their work. To conclude, I offer some implications and questions for further practice.

Mindfulness

Regular reflection can help us regain perspective and meaning. Mindfulness practice is rooted in Buddhism and other contemplative traditions; however, spiritual beliefs are not required for mindfulness, only the ability to be fully present and aware of one’s thoughts, emotions, and surroundings in the moment. Benefits of mindfulness practices are well documented, including improved decision-making, stress reduction, improved interpersonal skills, self-compassion, and holistic wellbeing. Mindfulness promotes creativity, resists the pressure to make quick decisions, and encourages consciousness of diverse perspectives, inclusivity, and motivation for positive change. Mindfulness allows one to reflect on past decisions and to recognize potential biases and assumptions emerging from one’s social position and those of our colleagues.

Ethical mindfulness (EM) is a specific approach to mindfulness that creates space for discernment in the face of ethical dilemmas. Sam and Gupton (2021) offered a six-step framework for faculty to practice being more attuned to the ethical implications of their work. Their approach adapts easily to the context of student affairs. First, practitioners are sensitized to “ethically important moments” (p. 89) and acknowledge them as worthy of concern. Second, practitioners explore personal biases and values, recognizing that an ethical moment can affirm or challenge their values. Third, by articulating ethical implications, practitioners consider consequences for all involved and use rational decision-making processes to articulate implications. Fourth, practitioners reflect on their biases and critically explore the motives, intentions, and assumptions that shape their actions. Fifth, practitioners demonstrate courage by breaking norms and challenging colleagues. Sixth, they take responsibility for the choices they make and commit to being a more ethical person. In sum, we learn to recognize and reflect on the sources of ethical dilemmas and create positive change by finding strength to take responsibility for what we control.

Applying Ethical Mindfulness

Before integrating it into my teaching, I share my story with students first, as an example and to build rapport around sharing difficult topics. As a former dean of students, I navigated a turbulent period at a small liberal arts college marked by high staff turnover and shifting priorities due to changes in the campus presidency almost every year. My role involved handling serious student misconduct cases. After a few months on the job, I noticed that whenever I initiated a disciplinary action, the parents of affluent student respondents would step in to bypass the process and appeal directly to the president. This intervention always led to my decisions being overturned in favor of privileged students, undermining my authority and the credibility of college’s disciplinary policies.

The campus’ moral climate was constantly in flux. Whomever the president was that year was the final authority, and their appeals decisions were driven by outside interests, like parents or a member of the board of trustees. While I was obligated to follow the rules, the people above me undermined my efforts. It was a performance. I was cast as the cruel, inflexible administrator; a scenario in which my enforcing the rules ended with the president or campus legal counsel swooping in to restore mercy and playing me the fool. Each day I went to work, I could feel my soul being sucked out of my body.

This pattern not only eroded my credibility but also reflected systemic injustice within the college and society at large, favoring privileged over marginalized students and those less privileged. I continually examined ethically concerning moments through the EM lens, and I saw no progress in addressing systemic injustices despite voicing objections. Despite my objections and appeals to the college’s espoused mission to advance social justice, my concerns were ignored. Desperate, I discussed my concerns with mentors and, indirectly, with senior leadership; however, the offensive practices were too deeply embedded in the college’s culture. Finally, I realized I needed to take responsibility by removing myself from a toxic climate, even though it meant leaving my job. I left to pursue a faculty career, valuing a setting where my integrity and professional values would be protected by academic freedom and at an institution where my values aligned with institutional policy and practice.

In examining this experience through the lens of EM, I took the first step of sensitivity to ethically important moments when I realized how students navigated the disciplinary process based on their connections. I acknowledged these moments as significant, the second step, as I saw how children of the wealthy who were usually white alumni received special treatment while students of color and those without connections had little recourse or leniency. In articulating ethical implications, the third step, I made the high stakes involved apparent, as I saw that justice, fairness, and accountability were continually compromised. I embodied the fourth step of being reflexive and recognizing standpoints and limitations in my reflection on the dissonance between my values and my identity as a white man, and the fluid moral climate at the college. I perpetuated a system that I despised and authorities more motivated to protect themselves than to uphold fair policies manipulated me, whom they obliged to enforce those policies. The fifth step of being courageous was manifest as I objected to the unfair practices and insisted on equitable disciplinary processes. Finally, the sixth step of taking responsibility was reflected in my decision to leave the institution, refusing to be part of an unjust system, and choosing a path that aligned with my personal and professional ethics.

Ethical mindfulness seems more painful than productive. Indeed, it is not a self-care regimen to increase happiness—at least in the short term. Although my experience left me angry and cynical, through regular practice I eventually renewed my commitment to pursue moral imperatives of social justice and fairness in other spaces. Ethical mindfulness is an ongoing process of reflecting that allows me to acknowledge and name the suffering I experience so that I gain control over my responses.

Ethical Mindfulness Assignment

In the last decade, many students have confided in me about the ethically challenging issues they are encountering in their work. Based on my experience with EM, I decided to incorporate it into my graduate and doctoral law and ethics courses. The goal was to guide students through a semester-long, introspective journey using the EM framework (Sam & Gupton, 2021). The learning outcomes were to enable students to recognize, reflect on, and articulate a plan to address ethical implications and improve their practice. In the first two weeks of the semester, students learn to recognize and articulate ethical implications according to Step 1 of the EM framework. They write a brief description of a critical ethical incident from their practice, identifying the ethical principles and values at stake and the consequences for stakeholders (Steps 2 & 3).

As members of a cohort, the students have already developed group norms and practices as part of their orientation to the program and before they enrolled in my class, such as listening without judgement, not interrupting others, and offering support. Nonetheless, I explicitly state upfront my expectations for privacy. What is shared in class should not be shared without permission. While I encourage students to be courageous in selecting an incident, students are not expected to divulge personal details. Incidents students chose to share range from the ordinary (e.g., difficult supervisors and microaggressive behavior in their work or assistantship environment) to tragic events, such as the impact of suicide and sexual assault on individuals and campus communities. Occasionally, a student will request to pass on discussing their experiences with others. In that case, I am happy to adapt the assignment in a way that still creates an opportunity for self-awareness and professional growth.

Over the next six weeks, students learn about ethical principles and apply them to their critical incidents via individual reflections and in dialogue with peers in class. Students complete the last three steps of the EM framework (Sam & Gupton, 2021) at the end of the semester. They critically evaluate their biases and positionality (Step 4), noting where they courageously challenged norms and systems (Step 5), and took responsibility for aligning their actions with their ethical values and principles (Step 6). It is important to emphasize that taking responsibility may mean seeking help for oneself, offering help to others, or both. The assignment concludes with a plan for addressing unresolved interpersonal and emotional challenges and an affirmation to incorporate EM into their leadership practice going forward.

The feedback from students regarding this assignment has been consistently positive. They appreciate the time during class devoted to exploring the emotional and physical symptoms that surround difficult decisions. Additionally, they value mindfulness as a critically self-reflexive and sustainable practice, which dispels the myth that ethics is only about not getting caught—a factor that often exacerbates anxiety and hinders the learning process. For me, this approach toward ethical decision-making is refreshing, moving beyond how to apply principles and checklists to generic case studies. Mindfulness operates in harmony with ethical codes and standards, fostering confidence in practitioners.

Implications for Practice

The sample assignment is a starting point for those who wish to explore ethical mindfulness and its applications to student affairs practice and pedagogy (see sample lesson at the end of this article). The EM framework can help practitioners to work through ethically challenging situations and articulate their concerns in a thoughtful and compelling way. Activities like journaling and meditation can build mindfulness over time, leading to more instinctively ethical responses. Although finding time in a busy schedule is challenging, practitioners can look for reflection time in their existing schedule, such as the commute, lunch break, or between meetings. Finding a peer interested in mindfulness who is willing to check in occasionally can also help with both the process and the accountability of embedding these practices in work.

For leaders in student affairs, the framework demonstrates the importance of authenticity, integrity, and courage in decision-making. Before launching division-wide initiatives promoting ethical mindfulness, leaders must begin with themselves, pausing to reflect on ethical dilemmas, recognizing their standpoints and biases, and accepting responsibility for their actions. They can set the tone for an ethical campus culture by allowing employees the space to engage in dialogue around ethical dilemmas and challenging situations, rather than immediately demanding solutions. Integrating mindfulness into professional development and highlighting examples of how it has been used effectively is also recommended.

Graduate preparation faculty can incorporate mindfulness practices into their introductory seminars and practice-based courses. The sample assignment demonstrates one approach instructors can take to integrate ethical reflection into coursework. Applying EM to real-life critical incidents from students’ practice provides students with tools to recognize and respond to challenges while building courage, reflexivity, and ethical discernment.

Ethical mindfulness is a process that individuals can use to recognize, reflect deeply on, and take responsibility for addressing ethical challenges. Practicing ethical mindfulness requires ongoing self-reflection and examining one’s values, beliefs, and biases – not an easy task amid the demands of professional life. Yet the rewards of greater integrity, responsibility, and shared commitment make the effort worthwhile. Benefits increase when leaders prioritize ethics by creating space for dialogue and modeling ethical discernment in professional practice and relationships. Though difficult, with commitment ethical mindfulness elevates both personal and institutional integrity.

Questions for Further Discussion

-

- What are some effective strategies for integrating mindfulness training into staff development programs at your institution? What challenges do you foresee?

- How might administrators foster a climate where all employees feel empowered to have courageous conversations around ethical issues?

- The sample assignment demonstrates one approach for facilitating student reflection on ethical decision-making in student affairs graduate preparation programs. What other co-curricular approaches could complement this type of reflective assignment?

References

American College Personnel Association (ACPA) & National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA). (2015). Professional competency areas for student affairs educators. Retrieved from http://www.naspa.org/images/uploads/ main/ACPA_NASPA_ Professional_Competencies_FINAL.pdf.

Charles, J. B. (2024, January 16). Amid national backlash, colleges brace for fresh wave of anti-DEI legislation. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/amid-national-backlash-colleges-brace-for-fresh-wave-of-anti-dei-legislation

Hollis, L. P. (2024, January 22). Dying to be heard? Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/01/22/tragedy-workplace-bullying-opinion

Sam, C. H., & Gupton, J. T. (2021). Ethical mindfulness: Why we need a framework for ethical practice in the academy. Journal of the Professoriate, 12(1).

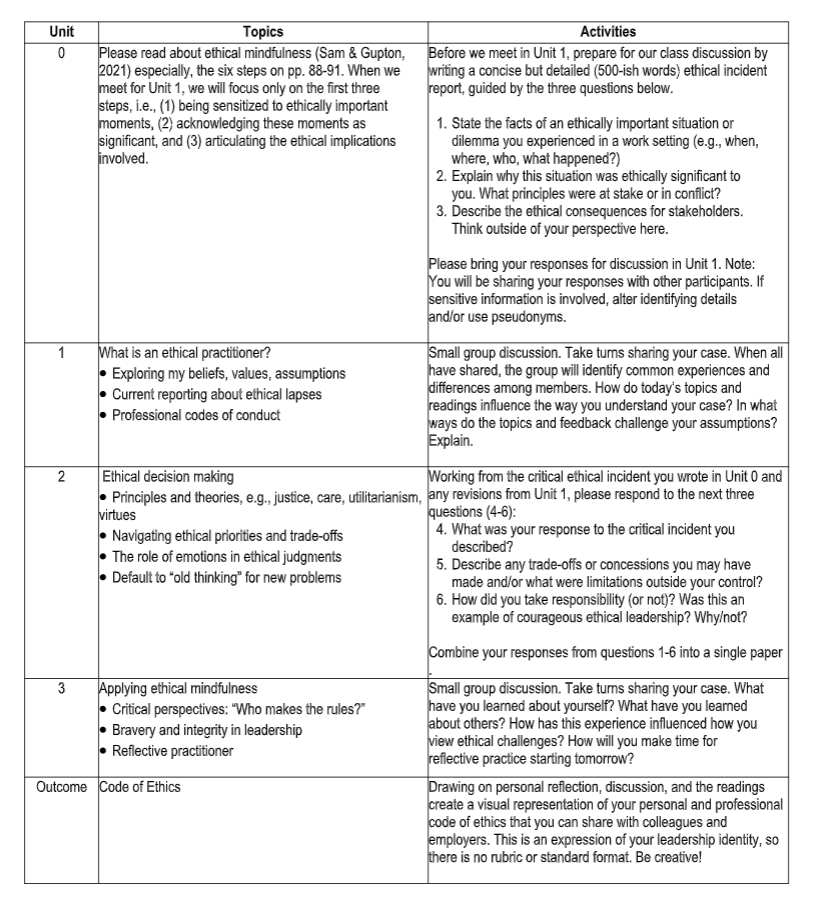

Sample Lesson Ethical Mindfulness

This lesson plan was adapted from my graduate-level course on law and ethics in higher education. The units are distributed over a 15-week semester. Unit 0 is preparation for the first unit that is dedicated to ethical mindfulness; thus, it can be assigned early in the course syllabus or as part of the initial communication before a training session begins. Topics and activities can be adapted to fit the audience and readings should fit the goals of the learning program.

About the Author

Jonathan J. O’Brien, Ed.D. (he/him/his)

jonathan.obrien@csulb.edu

Jonathan teaches Law and Ethics, Leadership, and Qualitative Research Methods in the master’s and doctoral programs at California State University, Long Beach. His research and consulting focus on ethical leadership in student affairs and higher education.