written by: Trisha Teig & DaShawn Dilworth

Abstract

Leadership education in student affairs must address inherent oppressive practices that exclude historically marginalized groups based on historical legacy, knowledge, capital, and practice. We have come to a point in the leadership educator community of practice to move beyond the “cool kids’ table” in the lunchroom. This part one of a two-part thought paper explores: how can we be honest and reflective about our past in order to realistically impact our present and future?

I remember my heart pounding, loudly enough I was surprised my co-workers could not hear it attempting to leave my chest. Like many other student affairs grad students, I was awaiting the news from potential summer internship sites. I remember the day we were supposed to hear back quite vividly; I did not hear back at all. While it was common to not receive a response on the first day, something felt odd as my number one internship site had relayed clear positive messaging that I would hear from them soon.

My first choice of internship involved the opportunity to work with an extended orientation leadership development program for first-year students – a dream of mine. When I did not hear back, I had the normal reaction of panic followed by questions: What happened? Did I not get it? Was I not good enough? The following day, I reached out. The response completely shifted how I viewed my work in higher education and how I viewed my understanding of identity within the field. The response could be seen as quite simple: “Thank you for your interest as you were a strong candidate and interviewer! However, we selected individuals who seemed they would be a better fit for our office and leadership team dynamic.”

Above being disappointed, I was simply confused about what they meant by “fit”. Was it because I did not work in a leadership center in my graduate assistantship? Was it because I did not have experience working in orientation programming? These questions cycled through my head. Then, when I learned who had been selected, I started asking myself another question: Was it because I did not look like everyone else working in this office?

Where We are Coming From

I (DaShawn) am a cisgender, heterosexual, Black man with an invisible disability. Despite countless opportunities facilitating leadership development training for undergraduate students, it took a long time for me to identify as a leadership educator. After attending the Leadership Educators Institute as a first-year master’s student, I began to see how leadership education was not confined to the walls of a leadership office or center as it did not belong to any one office. However, I soon reached a place of critical reflection on what it means to hold the label of leadership educator and how one obtains it. Through both the internship and job search processes as I described in the story above, I applied for roles centering on leadership training and education but I was often repeatedly not offered those positions. I started to question how the student affairs profession defines a leadership educator given that many of the offices I applied for positions went on to hire cisgender, white Women, which reflected both the leadership and most of the staff in those offices. I started to notice both a lack of Black and Brown spaces in these leadership education spaces, but also how sparingly the title of leadership educator was placed upon Black and Brown practitioners.

I reflected on my experiences of how I was socialized into various schools of thought surrounding leadership theory. From learning about servant leadership at the undergraduate level to a graduate course on leadership education at a large, public research institution, I take pleasure in continuing to expand my praxis as a leadership educator. However, I also question how exclusive the field of leadership education is and how it limits itself to the same scholars promoting the same schools of thought through the same lenses of identity and experience.

I (Trisha) am a straight, white, cisgender, Woman. I identify deeply as a leadership educator. The interaction of my social identities with my professional identity provides an opportunity for reflection and consideration within my teaching and research, particularly noting where I have had access to the leadership educator title and opportunities because of my identities.

I began my professional career in student affairs, progressing from my master’s program to hall director, to eventually an assistant dean of students. Within all of these professional roles, I sought out spaces to facilitate learning around leadership theory and practice. My student affairs training focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion, particularly in understanding critical and identity-based student development theories as crucial factors for professional preparation. Unfortunately, my leadership educator training was significantly lacking in comparison to those other areas. Sitting firmly in my privileged identities, it did not occur to me to link the curriculum on social identity development to how students develop as leaders.

After seven years in the field, I decided to become a leadership studies faculty member. I came to realize my main passion in work was facilitating leadership development for college students and actively engaged the practice of weaving critical and social justice foundations into all elements of leadership education. Creating spaces of belonging is a purposeful practice; I am interested in where we have the opportunity to reframe leadership education and de-center whiteness, masculinity, cisnormative, and heteronormative narratives by intentionally considering who and how we train folks to become leadership educators.

Historical Legacy

Leadership education is a field of study related to the teaching of leadership as both a theoretical concept and an experiential practice (Hall, 2018). With higher education, formalized leadership education grew out of a conversation in the 1980s among student affairs professionals to co-create a collective pedagogy and curriculum for leadership training and development for college students (Watkins, 2018). Currently, leadership education has grown into an entire field of inquiry and practice with over 1,500 leadership centers, schools, and academic majors, minors, and certificates across university spaces (Guthrie et al., 2018). Leadership education has quickly become more expected in the college experience (Watkins, 2018). This rapid growth produced a multitude of offerings deemed “leadership education”. In the past 10 years, a conversation arose about the need to train graduate students and emerging professionals as leadership educators (Andenoro & Skendall, 2020; Komives, 2011; Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Teig, 2018).

The accelerated growth of leadership learning and the need for more formally prepared leadership educators can be seen as an opportunity as we seek to grow strong, purposeful leaders for the future (Chunoo & Osteen, 2016). However, the rapid expansion has also driven the need to wrestle with power and privilege concerning our conceptualization of leadership (Guthrie et al., 2016; Dugan, 2017). Limited scopes of access are being revealed in tracing the lineage of who has been supported in learning to become a leader (Dugan & Henderson, 2021). Much like the history of higher education, leadership development for college students has focused on a small, select (white, male, Christian) audience (Mahoney, 2016; Thelin, 2011).

Critical scholars note leadership education as a high-impact practice (HIP) in higher education and as a foundational space to reify racist, sexist, and transphobic integrated assumptions to leadership development (Stewart & Nicolazzo, 2018; Wiborg, 2020). This lineage continues to fortify the historical legacy of exclusion within higher education created by the hegemonic regimes reproduced by institutions. In the last decade, some scholars began advocating for a reckoning of leadership in its connection with identity, power, and oppression, and a movement towards social justice as necessary to the conversation of leadership education (Beatty & Manning-Ouellette, 2018; Beatty & Tillapaugh, 2017; Dugan, 2017, 2021; Dugan & Humbles, 2018; Guthrie et al., 2016; Mahoney, 2016; Pendakur & Furr, 2016). There is also a larger emphasis on socially just leadership (Chunoo & Guthrie, 2018; Teig, 2017), culturally relevant leadership learning (Guthrie et al., 2016; Chunoo & Guthrie, 2018), and critical leadership pedagogy (Pendakur & Furr, 2016; Wiborg, 2020) to honor, acknowledge, disrupt, and reconstruct the history of exclusion within leadership development.

For all the positive steps forward, we focus this thought paper on how these changes have not permeated across the professionalization of leadership educators and analyze the disconnect between leadership education scholarship and leadership education practice. Little attention has been paid to who is facilitating leadership learning for college students and how their identities, networks, and practices shape students’ experience and access to leadership learning. Without both a depth and breadth of investigating identity, power, and oppression within leadership education, the historical legacy of exclusion continues to permeate the spaces within student affairs geared toward leadership education inquiry and practice.

The Leadership Education Lunchroom

Although the field of leadership education has advanced, there is still a large gap preventing leadership educator knowledge and practices from being accessible to everyone. To use a metaphor for the leadership education community of practice, let’s imagine it as a lunchroom. The long lines are made up of the scholars and practitioners facilitating the learning and development of new leaders: these are the leadership educators. Each group in the lunchroom finds a table to discuss new leadership knowledge and practice. However, one table gets higher status and not everyone is fortunate enough to get a seat there: the “cool kids’ table” (CKT). The members of the CKT are the trailblazers of leadership education: from scholars who helped develop widely used leadership theories or models such as the Leader Identity Development (LID) model to practitioners developing the most lauded leadership development programs such as Leadershape.

It can be easy to see how the CKT creates a sense of awe and a desire to join in the thought-provoking rich conversations presumed to be taking place there. But an alternative perspective would question why the leadership education “cool kids’ table” is so popular and who decides who can join? This creates a paradox in leadership education which permeates within the broader field of student affairs.

Research examining the “hidden who” of leadership education notes a vast majority of leadership educators are white and/or cisgender women (Jenkins & Owen, 2016). Furthermore, a deeper exploration of leadership educator identity development highlights how these professionals must encounter mentors and supportive environments to envision themselves as leadership educators in order to ascribe to that identity (Seemiller & Priest, 2015, 2017; Priest & Seemiller, 2018; Teig, 2018). If we consider how these two data points intersect (social identities of leadership educators + how leadership educators assume that identity) it is helpful to explore where possible exclusions or barriers exist. How and why did the CKT get constructed and how is it being reified in its own image?

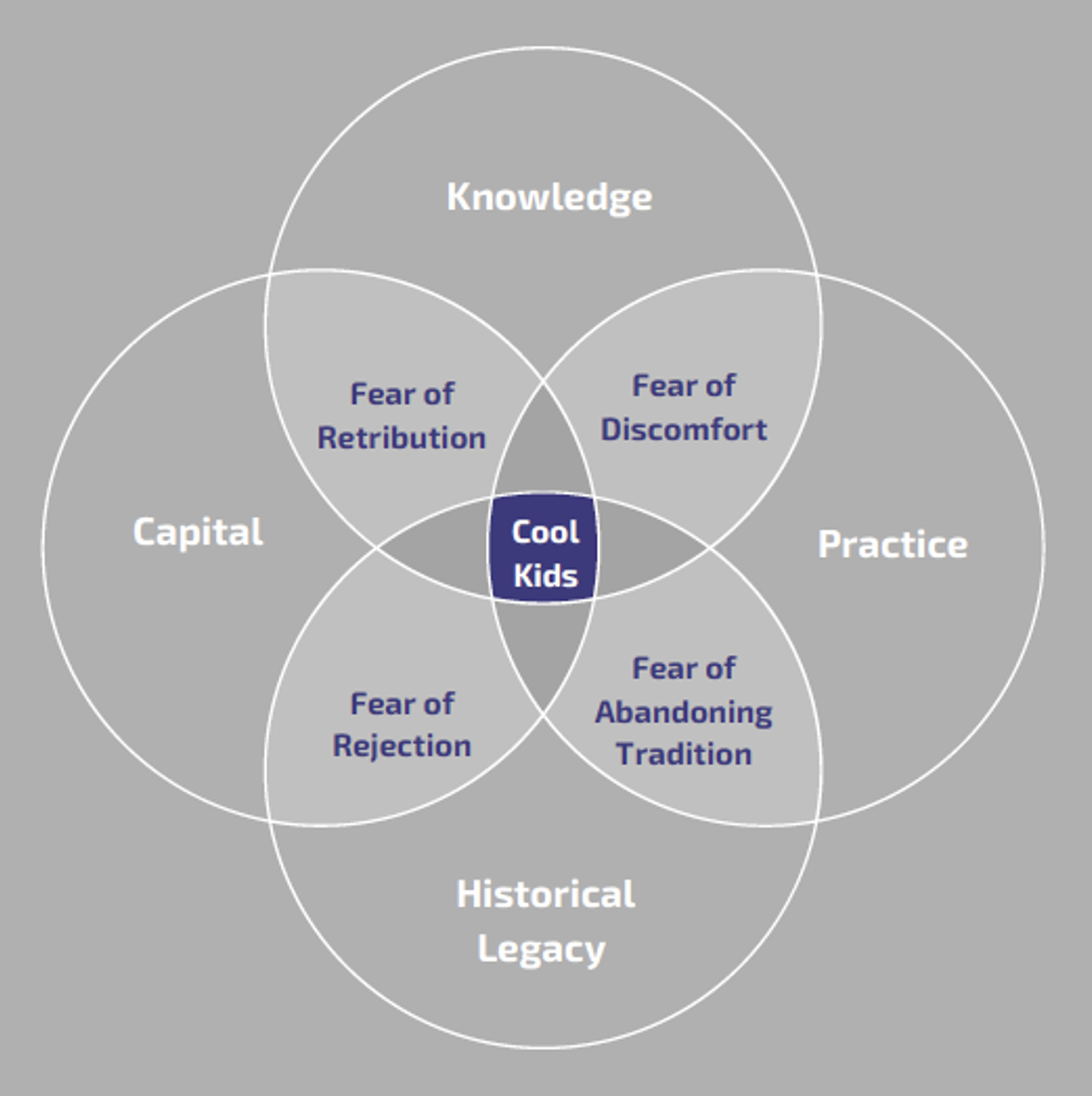

We posit this exclusion is rooted in oppressive systems keeping many professionals of Color and LGBTQ+ professionals from holding the title of leadership educator. In relation to leadership education, these boundaries can limit access to what is considered mainstream “leadership knowledge” and create an image of what a leadership educator is supposed to be (including what identities they hold, what knowledge they possess, and where they were educated). In turn, this draws divisions regarding what work professionals may or may not be doing in leadership education, which can further marginalize communities whose narratives may not be centered in the prescription of “leadership education”. These exclusions include three conceptual areas: exclusion by knowledge, exclusion by capital, and exclusion by practice, connected to the historical legacy of exclusion in leadership learning (See also Figure 1). We offer deeper examples of these exclusions and the fears that are produced as their drivers and outcomes.

Exclusion by Knowledge

Leadership education within student affairs is centered on an understanding of leadership knowledge and applied practice for college student development (Komives et al., 2011). The shaping of all disciplines includes canonical theory and foundations; leadership studies in higher education is no exception. However, it is relevant to consider limitations to this traditional collection of scholarship steeped in systems of oppression and require us to “consider who had or has the power to define the boundaries of leadership as a field” (Wiborg, 2020, p. 35). Exclusion by knowledge draws a boundary for who can be considered a leadership educator based on access and understanding of this limited leadership education collection of knowledge.

For example, among the leadership development and education communities in student affairs, there is an affinity for the Social Change Model of Leadership (SCM; HERI, 1996), Strengths (Tapia-Fuselier & Irwin, 2019), and the Leader Identity Development model (Komives et al., 2005). This affinity can have exclusionary effects if expanded critical perspectives are not also examined (Dugan & Henderson, 2021). For example, Tapia-Fuselier and Irwin (2019) analyzed Strengths through a critical whiteness lens to note limitations for students of Color.

The emphasis on training student affairs professionals as leadership educators is still a new endeavor with many HESA graduate programs (Jenkins & Guthrie, 2018; Kroll & Guvendiren, 2021; Teig, 2018). Kroll and Guvendiren (2021) identified in over 200 HESA programs, almost two-thirds (64%) have coursework related to leadership, some of this content is theory and practice-based (36%) or leadership theory focused (5%) but little to none of this coursework is focused on how to develop leadership in others. Considering this data, we question how and if an expansion of leadership education training and access to leadership education scholarship is occurring.

While it can be easy to perceive the normative focus on leadership education knowledge emerging within student affairs as fully expansive, this is simply not the case for many higher education institutions. This knowledge is still siloed in traditional canon, passed down from previous “cool kids” over the years. This can create a large gap amongst professionals based on their ability to attain more recent leadership education knowledge. This gap presents hazards to the field due to the increase of professionals being asked to perform leadership education without any training or formal education surrounding leadership (Kroll & Guvendiren, 2021; Teig, 2018).

Building on this challenge, we posit there is a collective, hegemonic narrative of leadership learning which creates a bubble of like-minded professionals utilizing the same mainstream (white-centric, heteronormative, cisnormative, color-evasive) leadership development content. Recent scholarship in critical leadership studies notes curricular and pedagogical training can offer resources foundational to new student affairs professionals in understanding their leadership educator identity (Chunoo & Guthrie, 2018; Teig, 2018; Wiborg, 2020). Like many fields of study, leadership education is evolving with new research and practices being created consistently; often making it hard for practitioners and programs to stay current. This hinders graduate students in programs who have assistantships or courses that only focus on more “popular” leadership knowledge which can place them at odds with graduate students who have the privilege of being at institutions where scholars are actively conducting new, relevant research (Kroll & Guvendiren, 2021).

We must also consider how many leadership theories are often rooted in white, patriarchal, cisnormative, and heteronormative assumptions of leadership preventing them from applicability to larger populations of students, particularly students of Color (Dugan & Henderson, 2021; Mahoney, 2016; Wiborg, 2020). Although a critical lens is being used to analyze and apply leadership theories in some scholarship (Dugan, 2017), it is taking time for these theories to become both public knowledge and widely accepted. This mirrors how many graduate preparation programs are not currently training their students on how to be leadership educators who educate for leadership efficacy, capacity, and identity through culturally relevant lenses (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Teig, 2018).

While knowledge privileges certain groups who are able to attain that knowledge, such as our proverbial cool kids, through the fortune of being in spaces where that knowledge is sequestered, knowledge proves to only be one piece of the puzzle. Even though knowledge can be limited to certain spaces, relationships and connection to social capital can provide a key into the more privileged areas of the leadership education space.

Exclusion by Capital

Social capital theory denotes the importance of collaborative relationships to advance collective efforts (Krile, 2014). As a theoretical concept, this seems ideal – we can progress by meeting others and building a network among those who share similar passions. These connections build on one another to progress our overall goals in a community or profession. However, the negative side to social capital is the inherent exclusionary (whether intentional or unintentional) nature of the practice. From professional nepotism (“Have you met so and so? We went to State together!”) to implicit bias (“Let’s hire her, she just seems like the right fit”), the emphasis on professional networks and social capital to advance in leadership educator professional spaces creates barriers.

“It’s not what you know, it’s who you know”. The student affairs profession is a large perpetrator of this mantra. As a highly social and engaged discipline, it is not surprising that we are keen to share connections with those we admire in the profession. These relationships are crucial to building a deep web of learning across our work. And yet, how often do we question this relational intertwining with a critical lens? Student affairs scholars Reece, Tran, DeVore, and Porcaro (2019) explored these questions in hiring “fit” and noted, “the practice of excluding others based on personal compatibility may allow more easily for cultural biases to influence hiring, onboarding, and the development of positive relationships at work” (p. 10).

As we enter the student affairs profession, often who you know, who knows you, and where you went to school are predictors for what type of job you can attain. This is particularly true for anyone who is seeking a role in leadership education (as referenced in the story at the beginning). As a (perceived) highly niche section of a small field, knowing the “cool kids” in leadership education often means doors are opened to you that would be closed for others. An invitation to the CKT offers support and direction, mentorship and sponsorship, opportunity to take on new roles, voice ideas, research and write scholarship, and gives the opening to meet more of the other cool kids’; a self-perpetuating cycle of advancement for some, but decidedly not all who are doing the work of leadership education.

If we dive deeper into the CKT, we notice that the very nature of an elite in-group often encourages new members within the image of themselves. As leadership education is mostly made up of white Women (Jenkins & Owen, 2016), the demographic makeup of those who “do” leadership education on college campuses often reflects our undeniably important and undeniably homogenous foremothers. While leadership education content is slowly making a shift towards inclusive, social justice, and critical lenses, how is this mirror being directed back at who we are socializing into the profession? Additionally, how does this impact which students participate in leadership programming if they do not see their identities reflected in the leadership educators? If the table is consistently a bunch of straight, white, cisgender Women and men, how does this inherently create an off-putting vibe for folx who do not hold those identities? If most people in leadership learning look the same, come from similar master’s programs, or know all the same “cool kids”, how can this self-defeating cycle come to an end?

Exclusion by Practice

When one pursues leadership education, knowledge and social capital help professionals enter the pipeline into the field while the emphasis on practice helps solidify one’s place once inside the pipeline. Many practitioners gain access to leadership education knowledge through practical experiences, such as graduate assistantships and internships (Tull et al., 2009). With an emphasis on practical experience within the student affairs job search, it is easy to assume those who have experience in positions with titles specifying “leadership” or work within a leadership center are more qualified for certain roles (Ardoin, 2014). However, to rely on this assumption is to give power to bias and create boundaries on who is allowed into the field. This insulates the field of leadership education within student affairs from new ideas and creates a wall of inequity, decreasing opportunities for practitioners and increasing a lack of representation.

Consider the title of “leadership educator”. Who is given the title and who gets to give the title? For instance, it can be easy to lend the title of leadership educator to graduate students who happen to hold assistantships in leadership offices or do “leadership-specific” work, but this is not founded on any metric. In thinking about efficacy, when does one begin to “feel like a leadership educator” or when does one know they are a leadership educator? Given this, there has to be consideration of how folks internalize the feelings associated with the title of leadership educator as well as experiences and role designation.

Knowing how exclusionary the title of leadership educator can be, the question becomes how do we support professionals who do not have “leadership” in their title? It can be easy to assume the title dictates the type of work done by the professional, but Teig (2018) made the argument professionals are asked to facilitate leadership development regardless of title or formalized training. The process of dismantling this exclusion by practice lies in two areas: professional development and graduate training in student affairs professional preparation programs.

Student affairs is a community based around the principle that practical experiences create stronger and more versatile professionals (Tull et al., 2009; Ardoin, 2014). An element of those practical experiences is professionals challenging themselves by engaging in continual learning in order to align with the pace of the field as it changes. Given that student affairs is not like other fields where there are certifications or exams necessary for continuing education, the field relies on the expectation of professionals engaging in professional development experiences such as workshops, trainings, and conferences to further their knowledge base. The profession has created useful professional development opportunities to address the gap in leadership education training. Programs like Leadership Educators Academy (LEA), Leadership Educators Institute (LEI), and conferences such as ILA and ALE do give some broadening to this need. However, these efforts are band aids or stop gap measures that do not allow for a broad level of access to leadership education knowledge for all student affairs professionals.

Furthermore, these experiences are not necessarily equitable to all those who wish to further their knowledge of leadership education practices. Conferences and workshops often require financial means to attend which places burdens on professionals if their institutions cannot afford for them to attend. Another challenge includes lack of departmental or institutional support in leadership education professional development for professionals who do not work in leadership departments but want to attend leadership-specific experiences. With barriers like these in place, it can be easy for leadership education professional development experiences to become silos of the same professionals sharing the same knowledge, continuing the cycle of privilege and ultimately a large majority of professionals from the space.

In thinking about graduate students, leadership education courses and training in graduate programs are sequestered within a small number graduate programs at large research institutions that often have faculty conducting related research (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2016; Kroll & Guvendiren, 2021). While graduate students at these large research institutions may benefit from the knowledge and relationships with faculty there, this still creates a large disparity across smaller graduate programs or institutions without the same access to that knowledge. There is also the creation of disparities of practice within graduate programs when graduate students who have assistantships within leadership offices are able to see themselves in leadership education in comparison to their peers because of the daily practice of their assistantship. In thinking about the next generation of professionals, there must be serious questions of how we restructure graduate programs to foster environments where everyone can see themselves as leadership educators, knowing they will be asked to “do” leadership education in their full-time roles (Teig, 2018).

Grappling with Fears

As these exclusions intersect, perpetuated fears contribute to the continuation of a CKT paradigm (See Figure 1). The interaction between exclusions and historical legacies creates fears of retribution, discomfort, rejection, and abandoning tradition. These fears are grounded in a space of perpetuating systems of power, privilege, and oppression and propagate the negative elements of the CKT.

Figure 1

Leadership Educator Exclusions + Fears

Figure Description: Four circles overlap to create a Venn diagram showing how foundations of a historical legacy of exclusion and specific exclusions of capital, knowledge, and practice interact to support and perpetuate fears. The overlap of the top circle, exclusion by knowledge, with the left circle, exclusion by capital, creates the space for fear of retribution. The overlap of the top circle with the right circle, exclusion by practice, produces the space for fear of discomfort. The bottom circle, historical legacy, overlaps with the left circle, exclusion by capital, to produce the space, fear of rejection. The bottom circle overlaps with the right circle, exclusion by practice, to create the space, fear of abandoning tradition. In the middle of the Venn diagram, where all four circles overlap, sits the “cool kids’ table”.

At the intersection of historical legacy and exclusion by practice is a fear of abandoning tradition. We imagine this fear includes concerns for how the traditional practices integrated into leadership education are impossible to let go, even if they are no longer useful to the profession.

When considering historical legacy and exclusion by capital, we envision a fear of rejection – rejection from the prevailing leadership education spaces if you are not a perfect fit or do not have access to the known cool kids who can support your leadership educator development.

In the overlap of exclusions by capital and knowledge, we can see a fear of retribution. Creating a space where your access to the leadership educator title is influenced by who and what you know, if you do push against or disrupt the system in place, possible negative ramifications may influence anyone striving for change. Finally, at the crossing of exclusions by knowledge and practice, we see a fear of discomfort. Champions of the CKT may be uncomfortable in following through with change the current status quo because it has most benefited those who have highest access. Recognizing a system that has privileged you to be a member of the CKT can cause discomfort and stifle the privileged to discourage or ignore calls for growth.

In this article, we have presented a challenging and dark outlook on the current state of leadership education in higher education/student affairs. It is not our intention to offer these critiques without also presenting arguments for how we can disrupt and reformulate leadership education as equitable and accessible for all professionals. In the second consideration of dismantling the cool kids’ table, we examine opportunities to make these changes. We can believe we can collectively disrupt this harmful status quo and move toward a more inclusive leadership education community of practice. In Part II of this thought paper, we will explore how purposeful questions and actions can lead us towards critical change in leadership education in student affairs.

References

Andenoro, A. C., & Skendall, K. C. (2020). The National Leadership Education Research Agenda 2020–2025: Advancing the state of leadership education scholarship. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(3), 33-38.

Beatty, C. C., & Manning-Ouellette, A. (2018). The role of liberatory pedagogy in socially just leadership education. In K. L. Guthrie & V. S. Chunoo (Eds.), Changing the narrative: Socially just leadership education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Beatty, C. & Tillapaugh, D. (2017). Masculinity, leadership, and liberatory pedagogy: Supporting men through leadership development and education. In P. Haber-Curran & D. Tillapaugh (Eds.), New Directions for Student Leadership: No. 154. Critical perspectives on gender and student leadership (pp. 47-58). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1002/yd.20239

Chunoo, V., & Guthrie, K. L. (2018). The imperative for action: Beyond the call for socially just leadership education. In K. L. Guthrie & V. S. Chunoo (Eds.), Changing the narrative: Socially just leadership education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Chunoo, V., & Osteen, L. (2016). Purpose, mission, and context: The call for educating future leaders. In K. L. Guthrie & L. Osteen (Eds.), New Directions for Higher Education: No. 174. Reclaiming higher education’s purpose in leadership development (pp. 9-22). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1002/he.20185

Dugan, J. P. (2017). Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives. Jossey-Bass.

Dugan, J. P., & Henderson, L. (2021). The complicit omission: Leadership development’s radical silence on equity. Journal of College Student Development, 62(3), 379-382. doi: 10.1353/csd.2021.0030

Dugan, J. P., & Humbles, A. (2018). A paradigm shift in leadership education: Integrating critical perspectives into leadership development. In J. P. Dugan (Ed.) New Directions in Student Leadership: No. 159, Integrating critical perspectives into leadership development, pp. 9-26. Jossey-Bass.

Guthrie, K. L., & Jenkins, D. M. (2018). The role of leadership educators: Transforming learning. In K. L. Guthrie (Ed.), Contemporary Perspectives on Leadership Learning (Vol. 1). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Guthrie, K. L., Teig, T. S., & Hu, P. (2018). Academic leadership programs in the United States. Tallahassee, FL: Leadership Learning Research Center, Florida State University.

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A social change model of leadership development (Version III). Los Angeles, CA: University of California Higher Education Research Institute.

Jenkins, D. M., & Owen, J. E. (2016). Who teaches leadership? A comparative analysis of faculty and student affairs leadership educators and implications for leadership learning. Journal of Leadership Education, 15(2), 98-113. doi: 10.12806/V15/I2/R1

Komives, S. R., Dugan, J. P., Owen, J. E., Slack, C., & Wagner, W. (2011). The handbook for student leadership development (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Kroll, J. R. & Guvendiren, J. (2021). Student affairs practitioners as leadership educators?: A content analysis of preparatory programs. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2021.1975547

Mahoney, A. D. (2016). Culturally responsive integrative learning environments: A critical displacement approach. In T. Bertrand Jones, K. L. Guthrie, and L. Osteen (Eds.), New Directions for Student Leadership: No. 152. Developing culturally relevant leadership learning (pp. 47-59). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1002/yd.20208

Pendakur, V., & Furr, S. C. (2016). Critical leadership pedagogy: Engaging power, identity, and culture in leadership education for college students of color. In K. L. Guthrie & L. Osteen (Eds.), New Directions for Higher Education: No. 174. Reclaiming higher education’s purpose in leadership development (pp. 45-55). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1002/he.20188

Priest, K. L., & Seemiller, C. (2018). Past experiences, present beliefs, future practices: Using narratives to re(present) leadership educator identity. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(1), 93-113. doi:10.12806/V17/I1/R3

Reece, B. J., Tran, V. T., DeVore, E. N., & Porcaro, G. (2019). From fit to belonging: New dialogues in the student affairs job search. In B. J. Reece, E. N. DeVore, E. N., G. Porcaro.,V. T. Tran, & S. J. Quaye, (Eds.), Debunking the myth of job fit in higher education and student affairs (pp. 1-26). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Seemiller, C., & Priest, K. L. (2015). The hidden “who” in leadership education: Conceptualizing leadership educator professional identity development. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(3), 132-151. Doi: 1012806/V14/I3/T2

Seemiller, C., & Priest, K. L. (2017). Leadership educator journeys: Expanding a model of leadership educator professional identity development. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(2), 1-22. doi: 10.12806/V16/I2/R1

Stewart, D. L., & Nicolazzo, Z. (2018). High impact of [whiteness] on Trans* students in postsecondary education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(2), 132-145. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2018.1496046

Tapia-Fuselier, N. & Irwin, L. (2019). Strengths so White: Interrogating StrengthsQuest education through a critical Whiteness lens. Journal of Critical Scholarship on Higher Education and Student Affairs, 5(1), 30-44.

Teig, T. (2018). Higher education/student affairs master’s students’ preparation and development as leadership educators. [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/2018_Su_Teig_fsu_0071E_14646

Teig, T. S. (2018). Integrating social justice in leadership education. In K. L. Guthrie & V. S. Chunoo (Eds.), Changing the narrative: Socially just leadership education (pp. 9-25). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A history of American higher education (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tull, A., Hirt, J.B., and Saunders, S.A. (2009). Becoming socialized in student affairs administration: A guide for new professionals and their supervisors. Virginia: Stylus Publishing.

Watkins, S. R. (2018). Contributions of student affairs professional organizations to collegiate student leadership programs in the late twentieth century. [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/2018_Su_Watkins_fsu_0071E_14360

Wiborg, E. R. (2020). A critical discourse analysis of leadership learning. (Order No. 28022412). [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. Proquest Dissertations Publishing.

Trisha Teig is a Teaching Assistant Professor of Leadership Studies at the University of Denver. She teaches and researches leadership development, inclusive leadership, and gender and leadership.

DaShawn Dilworth (he/him) is a Student Conduct Coordinator in the Office of Student Conduct at Virginia Tech.