written by: Sam P. Findley, M.A. and J. Metz, Ph.D.

Introduction

The number of student veterans enrolled in higher education increased nearly 340% from 2008 to 2016 according to the United States (US) Department of Veteran Affairs (VA; 2019). To meet the anticipated needs of this unique population of students, institutions of higher education (IHE) directed efforts at expanding and strengthening their support services (Sikes et al., 2020). Despite the increase in fiscal and human resources dedicated to supporting college student veterans, retention and graduation rates continue to remain low. Only a little over half of college student veterans enrolled in college complete a degree according to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute (PNPI; 2019). Of Student Veterans, 85% are categorized as non-traditional students due to age or marital status (PNPI, 2019).

At the same time, while the average college grade point average (GPA) of a student veteran is higher than that of a non-veteran student (Hill et al., 2019) this statistic is potentially misleading. Non-traditional students are historically associated with a higher GPA (Eppler et al., 2000; Hoyert & O’Dell, 2009). Recent research suggests that the average student veteran’s GPA (Hill et al., 2019) is equal to or lower than non-veteran college students when accounting for non-traditional status (Moore et al., 2020).

Our understanding of student veteran retention and academic achievement is limited. Very few IHEs disaggregate data to specifically look at this population (NASPA, 2013). This study offers insight into the factors contributing to the academic success and persistence of college student veterans.

Literature Review

The student veteran population consists of current service members (Active-Duty, Reserve Component, or National Guard) and those separated from their military service, commonly referred to as veterans. The definition of the term ‘veteran’ varies according to benefits offered by the VA and other agencies (VA, 2019b). Authors of this paper define student veterans as anyone currently attending an IHE who has served in one of the six branches of the US Armed Forces, regardless of length of service.

Starting in the late 2000s through the decade that followed, IHEs saw a significant increase in student veterans. A contributing factor to this increase was the passing of the Post 9/11 Veterans Education Assistance Act, commonly referred to as the “Post 9/11 GI Bill” (Dortch, 2018). In the 2007-2008 academic year, the year prior to the passing of the bill, student veterans using VA education benefits made up approximately 329,000, or 1.5% of total enrollment (Radford et al., 2009), and steadily increased to 1,132,860 (5%) student veterans using education benefits in the 2015-2016 academic year (VA, 2019a).

The influx of student veterans, as well as the response of IHEs, has resulted in a shift in research. Before the passing of the Post 9/11 GI Bill, student veterans were considered at-risk for academic success and degree attainment (Durdella & Kim, 2012). After the Post 9/11 bill research has become more divided. Qualitative studies have found that student veterans believe their military experience directly led to college success with the development resilience (Blaauw-Hara, 2016) or organizational skills (Norman et al., 2015). Comparative studies have shown that student veterans complete their degree at a higher rate (53.6%) and with lower attrition (28.4%) than non-veteran students (Cate et al., 2017). Additionally, researchers have noted that student veterans have a higher average GPA (3.34) compared to the national average (2.94) among civilian students (Hill et al., 2019).

However, this data can be misleading and provide a limited way of viewing student veterans (Young & Phillips, 2019). While military experience can lead to academic success, it can also lead to unique challenges that negatively impact grades and/or retention (Hinkson et al., 2021; Jenner, 2019). While providing important insight and access to information previously unattainable, these national comparative studies do not appear to compare these outcome measures by age, which is relevant when discussing a subpopulation of students where only 15% are within the traditional age group (18-24) for college attendance (PNPI, 2019). Non-traditional students historically have been found to have higher college GPAs than their traditional counterparts (Eppler et al., 2000; Hoyert & O’Dell, 2009) In current research Moore et al.(2020) found that non-traditional undergraduates reported a cumulative GPA of 3.39, with non-traditional graduate students reporting 3.71. This suggests that the 3.34 average GPA cited by Hill et al. (2019) is likely not outperforming, but on par or possibly underperforming when accounting for non-traditional status.

In short, academic achievement remains an area of concern for student veterans (Jenner, 2019) requiring further research to understand the student veteran experience. There is a significant catalog of research that annotates risk factors that exist for student veterans that lead to barriers in college (Jenner, 2017). Mental health is widely cited among researchers (Borsari et al., 2017; Jenner, 2019; Norman et al., 2015). In one study researchers found a significant difference in GPA among student veterans presenting with symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and those who did not (Hinkson et al., 2021). Student veterans experiencing mental health problems are also more associated with an increase in physical fights, hostility, and alcohol-related problems on college campuses (Borsari et al., 2017). These issues are further compounded by student veterans’ resistance to resources provided to them (Jenner, 2019; Norman et al., 2015).

Adapting to campus and civilian life is also well documented among veterans and has shown to have a negative impact on GPA (Borsari et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2018; Norman et al., 2015). Contributing factors include starting school after a break and balancing work, school, and personal responsibilities (Borsari et al., 2017; Jenner, 2017, 2019). Additionally, adapting to campus and non-military life requires student veterans to adjust to new structure, hierarchy, and expectations (Young & Phillips, 2019). The experience of cultural incongruence (McAndrew et al., 2019), and difficulty with peers and faculty (Barry et al., 2014) have both been shown to negatively impact academic performance as it affects student veterans’ sense of belonging (Young & Phillips, 2019). This lack of belonging can be particularly true for veterans who do not hold traditionally predominant or privileged identities in the military (white, straight, men) who may feel unseen on campus and may not utilize veteran resources (Meade, 2020).

Finally, studies have found that student veterans who could restructure their sense of identity and meaning experienced more positive integration into college, despite the presence of difficult or stressful events (Rumann & Hamrick, 2010). Leaving military service involves a re-definition of identity, that can feel overwhelming and lead to a loss of identity. The average age span of service members overlaps with when one traditionally develops, their identity and purpose in the world (Erikson, 1993). This leads to veterans leaving military service to navigate a new sense of identity as well as meaning and purpose at an older age than that of their non-veteran counterparts in a typical situation (Borsari et al., 2017; Rumann & Hamrick, 2010).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to contribute to research on the academic success and persistence of college student veterans. Specifically, this study explores the influence of stress, PTSD, social connectedness, college self-efficacy, college adaptation, and vocational meaning on college student veteran success, as measured by cumulative GPA, and persistence intentions. It was hypothesized that a combination of these factors would contribute to the variance in each outcome variable; however, there were no hypotheses concerning the independent influence of each predictor variable. Each of the variables chosen for inclusion in this study is theoretically derived and empirically supported through extant research.

Method

Participants

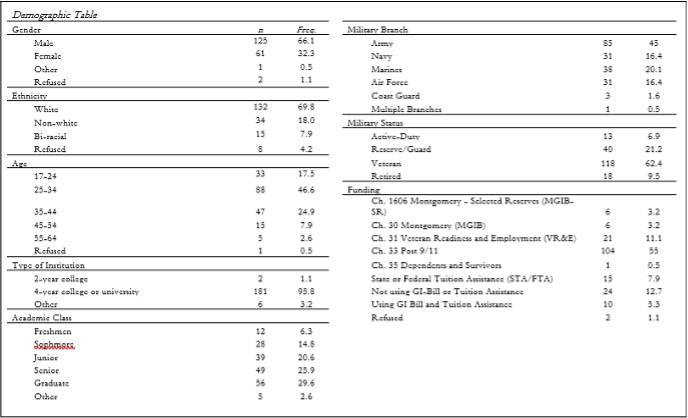

Table 1 provides a breakdown of demographic information within the sample. Total sample size was 189 student veterans primarily enrolled in 4-year institutions (95.8%) across the United States. Gender identity of the population was 66.1% Male, 32.5% Female, .5% identified as “Other,” and 1.1% did not respond. The ethnic breakdown was White (69.8%), Latinx/Hispanic (9%), Bi-racial (7.9%), Black (3.2%), Asian (2.1%), Indigenous (1.1%) and Middle Eastern (0.5%). Eight participants (4.2%) did not provide information on ethnicity. Several ethnicity categories had only 4 or fewer participants, to mitigate error, the categories were condensed to White (69.8%), Non-White (18%), Bi-Racial (7.9%) and Refused (4.2%). With respect to age, 17.5% were in the 17-24 age group, 46.6% were in the 25-34 age group, 24.9% were in the 35-44 age group, 7.9% were in the 45-54 age group and 2.6% were in the 55-64 age group. Academic class standing included 6.3% freshmen, 14.8% sophomores, 20.6% juniors, 25.9% seniors, 29.6% graduate students and 2.6% who were non-matriculated or in a trade program.

Military branch of service is as follows: 45% Army, 16.4% Navy, 20.1% Marines, 16.4% Air Force, 1.6% Coast Guard and .5% who served in the Army and Air Force. Military status of the sample was 6.9% Active-Duty, 21.2% Reserve/Guard, 62.4% Veteran and 9.5% Retired. A breakdown of the sources of funding is 3.2% using Ch. 1606 Montgomery – Selected Reserve (MG.I.B-SR), 3.2% using Ch. 30 Montgomery (MG.I.B), 11.1% using Ch. 31 Veteran Readiness and Employment (VR&E), 55% using Ch. 33 Post 9/11, .5% using Ch. 35 Dependents and Survivors (DAS), 7.9% using either State Tuition Assistance or Federal Tuition Assistance (STA/FTA), 5.3% using STA/FTA in conjunction with their G.I. Bill, and 12.7% are not currently using VA or TA education benefits. Two of the participants from this study did not respond to questions about funding. Some participants were dependents (spouse or child) of service members, who did not serve. These participants were omitted from the study and their responses were not used in data analysis.

Measurements

To understand factors important to academic success and retention, the following six measures were used: The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – 5th Edition (PCL-5), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the College Adaptation Questionnaire (CAQ), the Social Connectedness Scale – Revised (SCS-R), the College Self-Efficacy Inventory (CSEI), and the Vocational Identity Questionnaire (VIQ). The PCL-5 is a measure of PTSD while the PSS measures anxiety more globally. the CAQ will measure the level of distress student veterans are experiencing adapting to college, while the SCS-R will measure their sense of belongingness to campus. Additionally, the CSEI will measure the student’s perception of their confidence in activities deemed necessary to be successful in college. Finally, the VIQ will measure how much meaning the students attribute to their selected major and future career aspirations.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5). The PTSD Checklist (PCL) was created by researchers at the National Center for PTSD to be a self-report measure for PTSD symptoms (Bovin et al., 2015). The PCL-5 is used to measure the severity of PTSD according to the DSM-5 (Blevins et al., 2015). The PCL-5 displayed high test-retest reliability (r = 0.82) and high convergent validity (r = 0.84) with previous versions of the PCL, Posttraumatic Distress Scale (PDS), and Detailed Assessments of Posttraumatic Symptoms-Posttraumatic Stress Scale (DAPS). It also displays high internal validity (α = 0.96; Bovin et al., 2015).

Perceived Stress Scale. The 10-question Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) is a shortened version of the original PSS and is a self-report measure used to appraise one’s stress (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). The PSS-10 has been shown to have high internal validity (α= 0.74 – 0.91), strong retest reliability (r = 0.73, 0.90; Lee, 2012).

College Adaptation Questionnaire. The College Adaptation Questionnaire (CAQ) is an 18-question, self-report measurement used to assess how well students have adjusted to university life created Crombag (1968). Ten questions are negatively coded to indicate a lack of adjustment, while eight questions are positively coded to indicate adjustment (van Rooijen, 1986). The CAQ displays high internal validity (α = 0.89; Buckley et al., 2018).

Social Connectedness Scale – Revised. The Social Connectedness Scale – Revised (SCS-R) is a 20-question assessment rated on a 6-point Likert scale, with ten questions being negatively worded and ten questions positively worded (Lee & Robbins, 1995). The scale displayed high internal validity (α = 0.92; Williams & Galliher, 2006), moderate test-retest validity (1 month; r = 0.68), and strong criterion validity with other measurements assessing self-construct, self-esteem, loneliness, depression, and avoidance (R. M. Lee et al., 2001).

College Self-Efficacy Inventory. The College Self-Efficacy Inventory (CSEI) is a 20-question self-reported survey created by Scott Solberg to identify and measure the role that self-efficacy theory plays in academic performance. The assessment measures self-efficacy along four constructs: Self-efficacy for coursework, roommates, social interactions, and social integration (Solberg et al., 1993, 1998). The CSEI has strong correlations with pro-social and academic factors (e.g. coping with others, social efficacy) and negative correlations with factors dealing with stress (e.g. agitation, academic stress), suggesting good convergent and discriminant validity (Solberg et al., 1998). Researchers reported Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.86, 0.89, 0.79 for course, roommate and social self-efficacy, respectively (Solberg et al., 1993).

Vocational Identity Questionnaire. The Vocational Identity Questionnaire (VIQ) is a nine-question self-report survey designed to measure one’s sense of meaning in their work (Dreher et al., 2007). Authors of the measurement conducted validity testing by comparing the VIQ with the Work-Life Questionnaire (WLQ) and its corresponding subscales: Job, Career and Calling. The VIQ had a positive correlation with the WLQ subscale, Calling (r = 0.69) and a negative correlation with the remaining subscales of Job (r = -0.65) and Career (r = -0.37). Which highlights the VIQ’s measurement of intrinsic motivation. The Cronbach’s Alpha for the overall inventory was α = 0.84.

Measurements for Grade Point Average and Persistence Intention. GPA was measured using a self-report of cumulative GPA. Persistence intentions were measured by asking participants two questions. First, if they will be graduating at the end of the semester. If they were not graduating, they were asked if they plan on returning to their school the next semester. If they were graduating, participants were asked if they would have returned to their school if they were not graduating. Participants responded using a Likert scale from 1 “Definitely not” to 5 “Definitely yes”.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

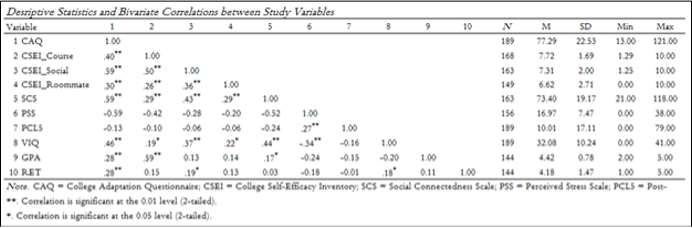

Descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented in Table 2. The mean score for college GPA was comparable to the national average for student veterans, 3.34 (Hill et al., 2019). Similarly, persistence intentions were high with a mean score of 4.18, suggesting a strong intention to continue with studies at their current school. This is consistent with findings in other studies such as Student Veterans of America’s foundational Million Records Project (Cate, 2014). Additionally, the mean score for the VIQ was also within the expected range in comparison to averages from other studies involving college students (Dreher et al., 2007). Mean scores for the CAQ, CSEI (all subscales), and SCS were moderately higher than expected. Standard deviation of the CAQ and SCS suggest more variation within those two measurements. The PCL-5 and PSS mean scores for this population were lower than expected.

Correlations

Table 2 also displays a correlation matrix of all non-demographic predictor variables (CAQ, CSEI, SCS, PSS, PCL-5, and VIQ) and outcome variables (persistence intentions and college GPA). As seen in the correlation matrix, most of the predictor variables were significantly correlated with each other. For example, the CAQ was significantly and positively correlated with CSEI-Course (r = 0.40), CSEI-Social (r = 0.59), CSEI-Roommate (r = 0.30), SCS (r = 0.59), and VIQ (r = 0.46). A similar trend was seen with CSEI-Course, CSEI-Social, CSEI-Roommate, SCS, and VIQ – these variables were all positively and significantly related to each other. The PSS was positively and significantly correlated with the PCL-5 (r = 0.27) and negatively correlated with the VIQ (r = 0-.34). The PCL-5 was not correlated with any variables other than the PSS. Regarding the outcome variables, GPA was positively and significantly correlated with CAQ (r = 0.28), CSEI-Course (r = 0.59), and SCS (r = 0.17). Persistence intention was positively and significantly correlated with CAQ (r = 0.28), CSEI-Social (r = 0.19), and VIQ (r = 0.18).

Analysis of Variance

A series of univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to determine differences in gender, race/ethnicity, age, year in school, funding for school, military branch, and military status in relation to GPA and persistence intention. There were significant differences in college GPA based on funding for school. Specifically, student veterans using Ch. 1606 of the G.I. Bill on average had lower GPAs than student veterans using other versions of the GI Bill, F(8, 135) = 2.259, p=.027. However, because this group only captured 3.2% of the participant sample, we did not control for this difference in the regression analyses. Additionally, a significant difference in GPA was found within the sample based on age, with student veterans in the 55-64 averaging a higher GPA than their colleagues F(4, 139) = 2.846, p=.026. Again, because this group only captured 2.6% of the participant sample, we did not control for this difference in the regression analyses No significant differences were found in any other variables regarding GPA. There was no significant difference in persistence intention within the sample based upon any descriptive variables mentioned above. Thus, no variables were controlled for in the regression analyses.

Multiple Linear Regression

Two separate multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the relative influence of the predictor variables on college GPA and persistence intention. Predictor variables included demographic variables (academic class, gender, ethnicity, age group, military branch, military status, funding) in addition to college adaptation (CAQ), college self-efficacy (CSEI-Course, CSEI-Social, CSEI-Roommate), social connectedness (SCS), vocational meaning (VIQ), perceived stress (PSS), and presence of PTSD symptoms (PCL-5). In both analyses, all factors were assessed within a regression model using the enter method.

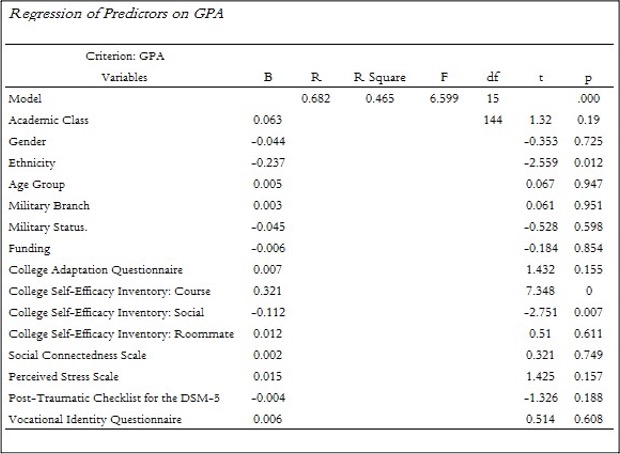

As seen in Table 3, academic class, gender, ethnicity, age group, military branch, military status, funding, and a combination of the above predictor variables accounted for 46.5% of the variance in GPA [F(15,144) = 6.599, p < 0.001.]. Significant individual predictors included ethnicity [β = -0.237, SE = 0.091, t (144) = -2.559, p = 0.012], CSEI – Course [β = 0.321, SE = 0.044, t (144) = 7.348, p < 0.001], and CSEI – Social [β = -0.112, SE = 0.041, t (144) = -2.751, p = 0.007].

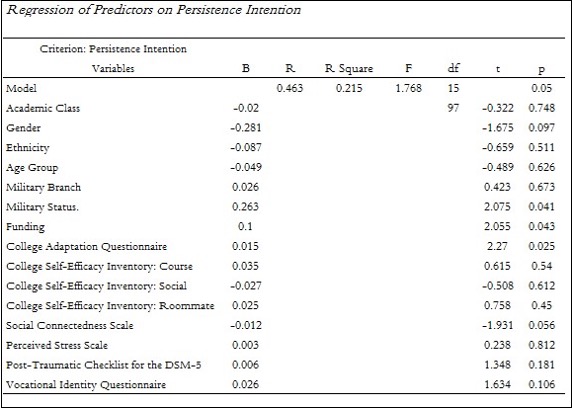

As seen in Table 4, academic class, gender, ethnicity, age group, military branch, military status, funding, and a combination of the above predictor variables accounted for 21.5% of the variance in Persistence Intention [F(15,97) = 1.768, p = 0.05]. Significant individual predictors included military status [β = 0.263, SE = 0.127, t (97) = -2.075, p = 0.041], type of funding [β = 0.100, SE = 0.049, t (97) = 2.055, p < 0.043], and College Adaptation Questionnaire [β = 0.015, SE = 0.006, t (97) = 2.27, p = 0.025].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of stress, PTSD, social connectedness, college self-efficacy, college adaptation, and vocational meaning on college student veteran success, as measured by cumulative GPA, and persistence intentions. Together, these variables accounted for 46% of the variance in GPA and 22% of the variance in retention. Ethnicity, course self-efficacy, and social self-efficacy were significant individual predictors of GPA. Military status, military funding and college adaptation were significant individual predictors of persistence intentions. Perceived stress and presence of PTSD symptoms did not play a role in academic success or retention in this sample of student veterans. The role of social connectedness and vocational identity are less clear. Although social connectedness was correlated with GPA in the bivariate correlation matrix and vocational identity was correlated with persistence intentions in the bivariate correlation matrix, neither variable was a significant individual predictor in the regression analyses. This could indicate complexity in these relationships and warrants further attention.

Predictors of GPA

Ethnicity was a significant independent predictor of GPA with non-white student veterans reporting lower GPAs. This aligns with existing research which found similar findings with students in general (Gehringer et al., 2021) and non-traditional students (Moore et al., 2020). The effects of discrimination and exclusion experienced by ethnically diverse students on campus are possibly exacerbated when considering other marginalized identities (e.g. age, gender, military status) of student veterans (Gehringer et al., 2021). Some have found marginalized identities lead to greater stress and less sense of belonging on campus among non-white student veterans (Smith, 2014). While student veterans have been found to persist and perform academically despite barriers (Cate et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2019), academic performance broken down by race of the student veteran is limited.

Self-efficacy was also found to be a significant independent predictor of GPA which aligns with existing research (Elliott, 2016; Gauthier, 2016). Something of note was the difference between the CSEI-Course and CSEI-Social variables. The positive beta score of CSEI-Course (β = 0.321) suggests that as a participant’s score in this subscale increased so did their GPA, which is to be expected. Interestingly, the CSEI-Social provided a negative beta score (β = -0.112), which suggests that lower scores in this subscale lead to improved GPA.

Course self-efficacy has been found to positively correlate with GPA among college students with learning disabilities (Hen & Goroshit, 2014), medical students (Taheri-Kharameh et al., 2018) and military cadets (Fosse et al., 2015). This study contributes to the student success literature by confirming that course self-efficacy significantly and positively relates to GPA among student veterans. The results of this study also suggest that too much socialization can interfere with academics among student veterans. To this point, Tinto (1988) argued that school transition occurs as a result of the student balancing between intellectual and social demands of college, and their inability to do so negatively affects long-term persistence. Student veterans cite fixed home and work responsibilities (Jenner, 2019) and difficulties socializing with traditional students (McAndrew et al., 2019; Sharp et al., 2015) which may mean socializing comes at the expense of academics. Bean & Metzner (1985) theorized that socialization in the collegiate environment is unimportant to non-traditional students and that overall the social needs are different than traditional students. With student veterans being considered a subpopulation of non-traditional students (Vacchi et al., 2017) findings from this study support Bean & Metzner’s theory that socialization in non-collegiate environment matters more to student veterans than socialization in college.

Predictors of Persistence Intention

Source of funding and military status were both found to be significant independent predictors of persistence intention. Findings in this study showed that lower rates of persistence were associated with student veterans identifying as Active-Duty or Reserves/Guard or were using older forms of the GI Bill namely the Montgomery GI Bill (MGIB) and the reservist component version, Montgomery GI Bill – Select Reserve (MGIB-SR). (Vacchi & Berger, 2014) This suggests that the current structuring of the GI Bill achieves stated goals of increasing academic performance and access to higher education for student veterans.

This study also found college adaptiveness was a significant independent predictor of persistence intention which complements and supports current research on student veterans (McAndrew et al., 2019). The CAQ, which measured college adaptiveness, was positively and significantly correlated with every variable in this study except the PSS and PCL-5. This suggests that college adaptiveness could function as a moderator/mediator with other predictors for academic outcomes.

Non-significant Predictor Variables

The PSS and PCL-5 were not significant individual predictors in the regression model predicting GPA or persistence intention. While previously published research has found that mental health and emotional well-being are predictors of academic success (Hinkson et al., 2021) and an area of concern for student veterans (Jenner, 2019) participants in this study did not endorse experiencing significant stress or trauma symptoms at the time they responded to the survey. It is possible that these factors function as a moderating relationship with low GPA but not higher GPA. This could explain the phenomenon observed by Borsari et al. (2017) which saw student veterans experiencing more severe symptoms of mental health than their civilian counterparts.

The VIQ was also not a significant predictor for GPA or retention in this sample. This is surprising as it was significantly correlated with persistence intention. These findings run contrary to previous research that highlights the role of intrinsic motivation and meaning (Dreher et al. 2007) Some research shows that meaning is activated in the presence of adversity among student veterans (Rumann & Hamrick, 2010). As such, it is possible that with an insufficient number of participants endorsing high levels of stress, meaning did not play a factor in this study. Alternatively, research has shown that student veterans attend college for different reasons and intentions than their non-military peers. It is possible that the VIQ, despite being normed on college students (Dreher et al., 2007), did not accurately measure meaning for student veterans.

Limitations

There are a few limitations associated with this study. This sample did not endorse perceived stress or trauma symptoms. While they were not factors for this sample, research has shown that mental health has meaningful impact on academic success (Hinkson et al., 2021) and is an area of concern for student veterans (Jenner, 2019). Therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited due to this sample not endorsing the presence of PTSD symptoms or distress.

A second limitation of this study is that although all the measures used in this study have been normed on college student populations, not all have been used with student veterans. It is possible that measures such as the CSEI-Social or the VIQ are not capturing the student veteran experience. While factors such as socialization and meaning were not predictors of GPA or persistence in this study, this could be attributed to the measures used as opposed to the factors not being relevant to the outcome measures.

A third limitation is related to how GPA was requested in the survey. In this study, GPA was divided into categories and participants were asked to select their GPA category. Authors expected that the students in this sample would have higher GPAs and thus artificial categories were made to create variance. However, categorizing a continuous variable may have consequences such as loss of statistical power, underestimating the variance, residual confounding, and obscuring non-linearity.

Implications for Research and Practice

Research

An interesting finding from this study was the impact of identity on academic success among student veterans. Ethnicity was a significant independent predictor of GPA with non-white student veterans reporting lower GPAs. This matches existing research which found similar findings with students in general (Gehringer et al., 2021) and non-traditional students (Moore et al., 2020). The effects of discrimination and exclusion experienced by ethnically diverse students on campus are possibly exacerbated when considering the intersectionality of other marginalized identities of student veterans (Gehringer et al., 2021), such as gender, age, and military status. Marginalization is complex and difficult to fully capture within one variable such as ethnicity, especially when the sample of ethnically diverse student veterans is so small compared to their White counterparts. While research has shown a connection between ethnicity and academic success of college students, research on the impact of race and ethnicity on the student veteran experience is scarce.

This dearth of research extends to other identities as well. Military status (i.e., Active-Duty, Reserves, National Guard) is an identity that is can be overlooked by IHEs and the VA but are salient and impactful for the student veteran. A student veteran’s military status is directly related to funding they are eligible for which was also a significant contributor to persistence found in this study. Further research is needed to truly capture this phenomenon. Student veterans currently serving in the military experience additional disruptions in their schooling due to their military obligation, such as deployments and training. The extent that these factors effect persistence in college is unclear. What is clear that military status plays a role in the academic achievement and persistence of student veterans.

Practice

These findings also highlight the limitations of the CSEI in capturing the lived experience of non-traditional students such as student veterans. At this moment, research in the field of student veterans regarding academic self-efficacy is limited. While self-efficacy has been found to be a mediator for academic and military performance (Fosse et al., 2015), samples studied were cadets in a military academy. This poses stark differences to the general student veteran population in terms of age and stage of life (Borsari et al., 2017) which makes up the majority of the student veteran population (PNPI, 2019) Additionally, non-traditional students, of which student veterans are a subpopulation, have various reasons for attending college that do not always align with academic attainment or achievement (e.g., work promotion, interest pursuits, etc.). As such, it is possible that responses reflected factors that were not considered for this study. Research looking into developing assessments that more accurately measure the student veteran experience are warranted. Findings from this study could be used to conduct qualitative research such as interviews or focus groups with student veterans to provide deeper, richer data on factors that matter and affect

This study informs factors for colleges and universities to consider in supporting student veterans. For example, a college transition course designed specifically for student veterans could help student veterans adapt to college and develop self-efficacy by teaching academic skills, promoting peer and instructor socialization, connecting to academic, financial, and mental health resources, and through goal setting. Student veteran support offices could promote self-efficacy and adaptation to college through support groups, peer mentoring, guest speakers, advising, or newsletters providing academic and financial resources.

Centers and staff working with student veterans and address need to disrupt stereotypical and homogeneous perceptions of student veterans by develop programming that appeals to diverse interests, stages of development, and experience, and work with other organizations to create more inclusive events or partnerships. Finally, this study shows that IHEs might need to re-evaluate or reconsider how they address the socialization needs of student veterans. Focusing on programming that is function-based such as service projects, networking luncheons, or workshops for skill-building could be of more benefit for student veterans.

Conclusion

With an unprecedented number of student veterans attending IHEs across the US, it is worthwhile to better understand what factors can predict academic success. This study contributes to building knowledge of research regarding student veterans by helping centers and staff working with student veterans to understand what is working with this population and what can be improved to help student veterans with academic success. As institutions evolve and improve efforts, they become the catalyst that transforms goals into reality and help student veterans achieve a well-earned successful life.

References

Barry, A. E., Whiteman, S. D., & Wadsworth, S. M. (2014). Student service members/veterans in higher education: A systematic review. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 51(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2014-0003

Bean, J. P., & Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of Educational Research, 55(4), 485–540. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543055004485

Blaauw-Hara, M. (2016). “The military taught me how to study, how to work hard”: Helping student-veterans transition by building on their strengths. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(10), 809–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2015.1123202

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

Borsari, B., Yurasek, A., Miller, M. B., Murphy, J. G., McDevitt-Murphy, M. E., Martens, M. P., Darcy, M. G., & Carey, K. B. (2017). Student service members/veterans on campus: Challenges for reintegration. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000199

Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2015). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

Buckley, C. Y., Whittle, J. C., Verity, L., Qualter, P., & Burn, J. M. (2018). The effect of childhood eye disorders on social relationships during school years and psychological functioning as young adults. British and Irish Orthoptic Journal, 14(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.22599/bioj.111

Cate, C. A. (2014). Million records project: Research from Student Veterans of America. https://studentveterans.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/mrp_Full_report.pdf

Cate, C. A., Lyon, J., Schmeling, J., & Bogue, B. Y. (2017). National veteran education success tracker: A report on the academic success of student veterans using the post-9/11 GI bill. https://studentveterans.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NVEST-Chapter-Toolkit.pdf

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. M. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (4th ed., pp. 31–67). Sage.

Crombag, H. F. M. (1968). Studiemotivatie en studieattitude (1st ed.). Wolters – Noordhoff.

Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019). 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf

Dortch, C. (2018). The post-9/11 GI bill: A primer. www.crs.gov

Dreher, D. E., Holloway, K. A., & Schoenfelder, E. (2007). The vocation identity questionnaire: Measuring the sense of calling. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 18, 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004158511.i-301.42

Durdella, N., & Kim, Y. K. (2012). Understanding patterns of college outcomes among student veterans. Journal of Studies in Education, 2(2), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v2i2.1469

Elliott, D. C. (2016). The impact of self beliefs on post-secondary transitions: The moderating effects of institutional selectivity. Higher Education, 71(3), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9913-7

Eppler, M. A., Carsen-Plentl, C., & Harju, B. L. (2000). Achievement goals, failure attributions, and academic performance in nontraditional and traditional college students. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 15(3), 353–373.

Erikson, E. (1993). Childhood and Society (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Fosse, T. H., Buch, R., Säfvenbom, R., & Martinussen, M. (2015). The impact of personality and self-efficacy on academic and military performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Military Studies, 6(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/jms-2016-0197

Gauthier, L. (2016). Redesigning for student success: Cultivating communities of practice in a higher education classroom. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 16(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v16i2.19196

Gehringer, T. A., Folberg, A. M., & Ryan, C. S. (2021). The relationships of belonging and task socialization to GPA and intentions to re-enroll as a function of race/ethnicity and first-generation college student status. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000306

Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2014). Academic procrastination, emotional intelligence, academic self-efficacy, and GPA: A comparison between students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219412439325

Hill, C. B., Kurzweil, M., Davidson, E. P., & Schwartz, E. (2019). Enrolling more veterans at high-graduation-rate colleges and universities. https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/enrolling-more-veterans-at-high-graduation-rate-colleges-and-universities/

Hinkson, K. D., Drake-Brooks, M. M., Christensen, K. L., Chatterley, M. D., Robinson, A. K., Crowell, S. E., Williams, P. G., & Bryan, C. J. (2021). An examination of the mental health and academic performance of student veterans. Journal of American College Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1858837

Hoyert, M., & O’Dell, C. (2009). Goal orientation and academic failure in traditional and nontraditional aged college students. College Student Journal, 43(4), 1052–1061. https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=c817ea0e-6a96-4528-ac75-c5d0d9d4b06c%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3D%3D#AN=55492482&db=pbh

Jenner, B. M. (2017). Student veterans and the transition to higher education: Integrating existing literatures. Journal of Veterans Studies, 2(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.14

Jenner, B. M. (2019). Veteran success in higher education: Augmenting traditional definitions. Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Study, 14(1), 25–41.

Lee, E. H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Lim, J. H., Interiano, C. G., Nowell, C. E., Tkacik, P. T., & Dahlberg, J. L. (2018). Invisible cultural barriers: Contrasting perspectives on student veterans’ transition. Journal of College Student Development, 59(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0028

McAndrew, L. M., Slotkin, S., Kimber, J., Maestro, K., Phillips, L. A., Martin, J. L., Credé, M., & Eklund, A. (2019). Cultural incongruity predicts adjustment to college for student veterans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(6), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000363

Meade, V. (2020). Embracing diverse women veteran narratives: Intersectionality and women veteran’s identity. Journal of Veterans Studies, 6(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.v6i3.218

Moore, E. A., Winterrowd, E., Petrouske, A., Priniski, S. J., & Achter, J. (2020). Nontraditional and struggling: Academic and financial distress among older student clients. Journal of College Counseling, 23(3), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12167

Norman, S. B., Rosen, J., Himmerich, S., Myers, U. S., Davis, B., Browne, K. C., & Piland, N. (2015). Student veteran perceptions of facilitators and barriers to achieving academic goals. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 52(6), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2015.01.0013

Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2019, November 9). Factsheets: Veterans in Higher Education. https://pnpi.org/veterans-in-higher-education/

Radford, A. W., Wun, J., & Weko, T. (2009). Issue tables: A profile of military servicemembers and veterans enrolled in postsecondary education in 2007-08. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009182.pdf

Rumann, C. B., & Hamrick, F. A. (2010). Student veterans in transition: Re-enrolling after war zone deployments. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(4), 431–458.

Sharp, M.-L., Fear, N. T., Rona, R. J., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., Jones, N., & Goodwin, L. (2015). Stigma as a barrier to seeking health care among military personnel with mental health problems. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37(1), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxu012

Sikes, D. L., Duran, M. G., & Armstrong, M. L. (2020). Shared lessons from serving military-connected students. College Student Affairs Journal, 38(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1353/csj.2020.0013

Smith, N. (2014). More than White, heterosexual men: Intersectionality as a framework for understanding the identity of student veterans. Journal of Progressive Policy & Practice, 2(3), 229–238.

Solberg, V. S., Gusavac, N., Hamann, T., Felch, J., Johnson, J., Lamborn, S., & Torres, J. (1998). The adaptive success identity plan (ASIP): A career intervention for college students. The Career Development Quarterly, 47(1), 48–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1998.tb00728.x

Solberg, V. S., O’Brien, K. M., Villareal, P., Kennel, R., & Davis, B. (1993). Self-efficacy and Hispanic college students: Validation of the college self-efficacy instrument. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863930151004

Taheri-Kharameh, Z., Sharififard, F., Asayesh, H., Sepahvandi, M., & Hoseini, M. H. (2018). Relationship between academic self-efficacy and motivation among medical science students. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 12(7), JC07-JC10. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2018/29482.11770

Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of student departure: Reflections on the longitudinal character of student leaving. The Journal of Higher Education, 59(4), 438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1981920

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019a). Annual Benefits Report – Education. https://www.benefits.va.gov/gibill/mgib_sr.asp

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019b). Verification Assistance Brief. http://www.va.gov/osdbu.

Vacchi, D. T., & Berger, J. B. (2014). Student veterans in higher education. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. 29, pp. 93–151). Springer. http://www.daneshnamehicsa.ir/userfiles/files/1/12- Higher Education_ Handbook of Theory and Research_ Volume 29.pdf#page=106

Vacchi, D. T., Hammond, S., & Diamond, A. (2017). Conceptual models of student veteran college experiences. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2016(171), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.20192

van Rooijen, L. (1986). Advanced students’ adaptation to college. Higher Education, 15(3–4), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00129211

Williams, K. L., & Galliher, R. V. (2006). Predicting depression and self–esteem from social connectedness, support, and competence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(8), 855–874. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.855

Young, S. L., & Phillips, G. A. (2019). Veterans’ adjustment to college: A qualitative analysis of large-scale survey data. College Student Affairs Journal, 37(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1353/csj.2019.0003

Author Biographies:

Sam P. Findley, M.A. – Sam is a combat veteran having served 11 years in the Utah National Guard. He is currently earning his PhD in counseling psychology at the University of Utah and will continue his military career following graduation as a uniformed psychologist in the Air Force.

J. Metz, Ph.D. – Dr. A.J. Metz is an Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Utah. Her research examining non-cognitive factors related to academic success and career development in underrepresented and underserved student populations has led to numerous journal articles, book chapters, conference presentations, workshops, and most recently, a student success textbook and norm-referenced self-assessment tool, ACES, the Academic and Career Excellence System.

Appendix:

Table 1:

Table 2:

Table 3:

Table 4: