Mary Alice Varga

University of West Georgia

Everyone Grieves Differently: A Holistic Perspective to Identifying and Supporting College Student Grief and Trauma

While the 2020 year is coming to a close, many students’ grief and trauma will continue into the new year. The disruptions to our campuses, communities, and everyday lives requires us to quickly change and adapt to a new usual way of life, both in ourselves and with others. On top of change, trauma and grief experiences can cause an unbelievable amount of stress and anxiety with many different effects. Combine this stress and anxiety with collegiate life, and emerging adults and higher education administrators are faced with an unpredictable future that can feel daunting and difficult to manage. Recent research already shows that college students are experiencing increased stress, anxiety, depression, isolation, and difficulty concentrating during the pandemic and utilizing healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms (Son, Hegde, Smith, Wang, & Sasangohar, 2020). Additional understanding of how students respond to the pandemic in holistic ways can lead to better approaches to supporting them.

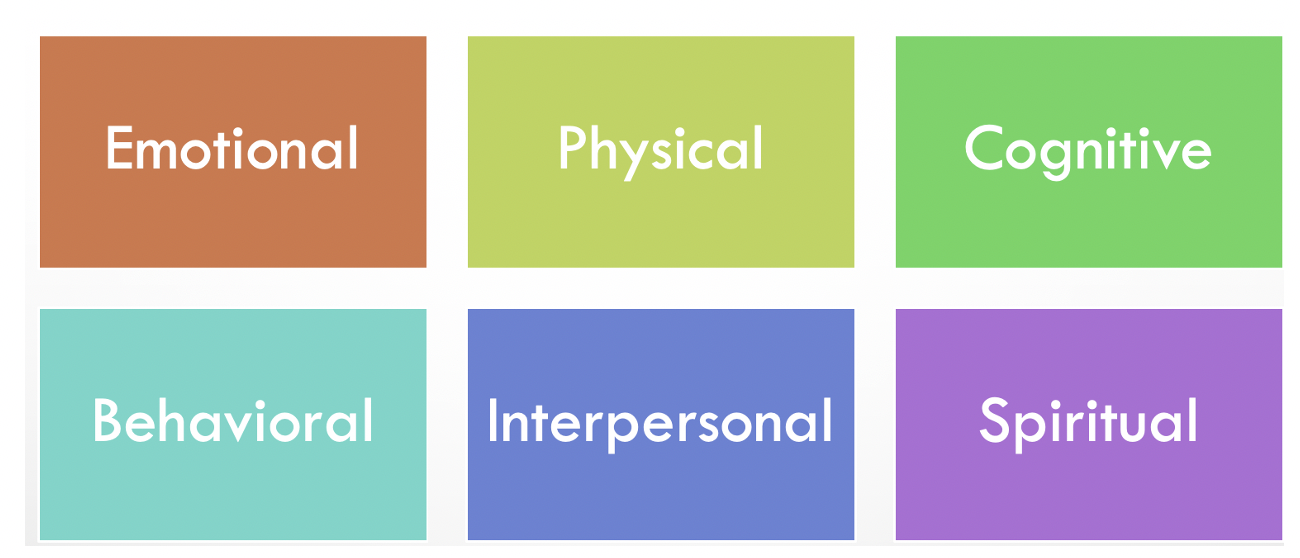

The Professional Competencies for Student Affairs Educators (ACPA/NASPA, 2015) outlines wellness as encompassing “emotional, physical, social, environmental, relational, spiritual, moral, and intellectual elements” (p. 16). The Holistic Impact of Bereavement model, used as a framework for this paper, have similar elements (see Figure 1). The elements are outlined as six dimensions, including emotional, cognitive, behavioral, physical, interpersonal, and spiritual/philosophical effects (Balk, 2011; Varga, 2015). Using these two frameworks, we can outline practical ways to 1) identify the various non-clinical ways students are affected by grief and trauma; 2) help students identify these effects in themselves, and 3) outline explicit ways campuses can provide support.

Figure 1. Holistic Grief Effect Dimensions

Holistic Grief Effects

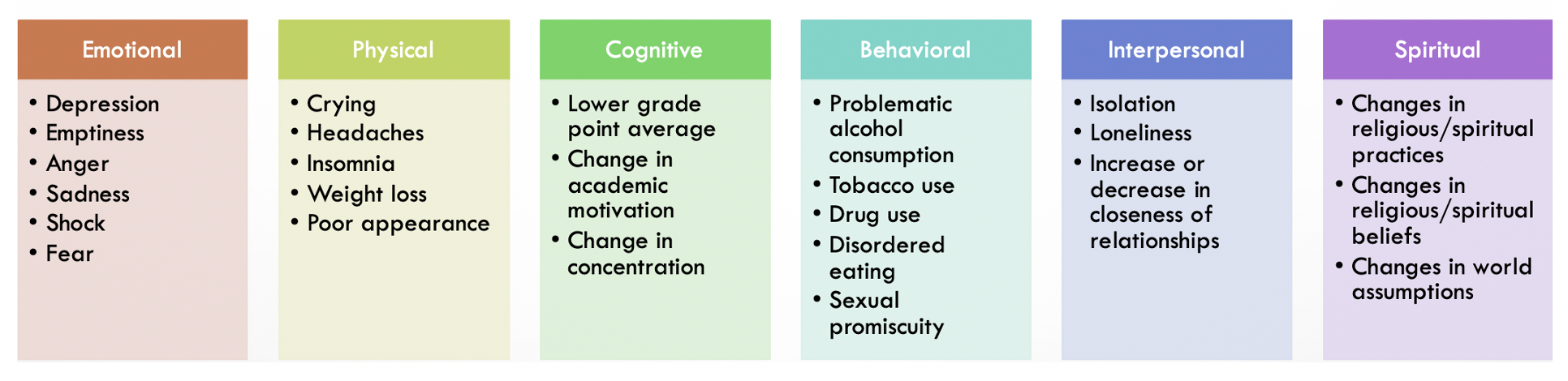

Research on holistic grief experiences indicates that people grieve in different ways. Trauma responses, such as those triggered by a pandemic, can be similar. We can notice changes in ourselves and others that are emotional, cognitive, behavioral, physical, interpersonal, and spiritual/philosophical (Balk, 2011; Varga 2015) as outlined in Figure 2.

Emotional Effects

When the landmark study on college student loss was conducted (LaGrand, 1981), depression was the most frequent emotional feeling reported by students, followed by emptiness and anger. When LaGrand (1985) expanded the 1981 study on college student loss, including an additional 2,000 students, depression remained the most frequent emotion reported by students. LaGrand’s findings continued to be substantiated by subsequent studies examining college student grief effects. Students’ emotional reactions consistently included sadness or depression, anger, shock, disbelief, fear, and denial (Balk, 1997; Balk & Varga, 2018; Varga, Bordere, & Varga, 2020). We already see these effects as students report their reactions to the pandemic (Son et al., 2020).

Physical Effects

Physical grief effects have also been identified in college student bereavement. LaGrand (1985) outlined that crying remained the most frequent physical reaction, followed by headaches and insomnia. Insomnia in bereaved students is significant because those experiencing insomnia are also at risk of developing complicated grief symptoms (Hardison, Neimeyer, & Lichstein, 2005). Physical effects can also include weight loss, poor appearance, aggression, loss of energy, and insomnia (Vickio, Cavanaugh, & Attig, 1990).

Cognitive Effects

Grief can affect cognitive functioning in students. Bereaved students have shown statistically significantly lower grade point averages during the semester a loss was experienced compared to matched peers (Servaty-Seib & Hamilton, 2006). Students who were close to the deceased are five times more likely to experience changes in motivation and four times more likely to experience changes in concentration (Walker, Hathcoat, & Noppe, 2012), which is an effect of the pandemic as well (Son, et al., 2020). Furthermore, the closer students are with the deceased, the more academic struggles they encountered due to changes in motivation and concentration (Walker et al., 2012).

Behavioral Effects

Bereaved college students experience behavioral grief effects. These effects include behaviors such as problematic alcohol consumption, tobacco use, or drug use. (Balk, 2011). Disordered eating can also occur. Beam, Servaty-Seib, and Mathews (2004) found that female undergraduate students who experienced parental loss may be at high risk for anorectic-related cognitions and behaviors. Disordered eating (Balk & Vesta, 1998), sexual promiscuity (Balk, 2011) are behaviors linked to grief, along with a connection between increased death awareness and increased engagement in risky sexual behavior (Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2004).

Interpersonal Effects

Bereaved college students can also experience interpersonal grief effects. Isolation and loneliness are often reported (Balk, Tyson-Rawson, & Colletti-Wetzel, 1993). Students can perceive grief as prompting an increase in relationships’ closeness, decreasing closeness, or straining relationships (Vickio et al., 1990). Change in peer relationships can be perceived more by grieving students with mental health difficulties (Cupit et al., 2016). Even though peers often want to support their bereaved friends, non-bereaved peers can become uncomfortable when finding out their friend has experienced a loss and is grieving (Balk et al., 1993; Parikh & Servaty-Seib, 2013). Varying expectations in grief recovery between bereaved and non-bereaved peers can also impact interpersonal connections (Balk, 1997).

Spiritual Effects

Spiritual, religious, and philosophical effects among grieving undergraduate students have been explored. Students engage in religious practices to cope with loss (Balk, 1997; Balk, 2008). Schwartzberg and Janoff-Bulman (1991) found that bereaved students believed in a less meaningful world than non-bereaved students. Bereaved students also reported believing that events happen more by chance and lacked control. More recent studies have shown that loss affects the worldviews or world assumptions that college students have (Pollard et al., 2017; Varga & Varga, 2019). World assumptions are “changes in thoughts regarding religion or spirituality” (Pollard et al., 2017, p. 7). Positive and negative religious coping methods have been linked to college students experiencing adverse life events (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000). The rare life event of a pandemic is no exception, and thoughtful approaches to healthy coping are necessary. Understanding the various ways students can be affected by loss and trauma situations allows us to assist students with effective coping strategies better.

Holistic Campus Support

The ability to correctly identify trauma and grief effects is imperative when it comes to coping and support. Bereaved students do not always know that the effects they are experiencing are connected to grief or trauma. University staff, faculty, and counseling support can help students recognize effects they may be experiencing and how to mitigate adverse effects. This practice is especially important since grief effects such as insomnia and depression can lead to complicated grief or persistent complex bereavement (Mash, Fullerton, Shear, & Ursano, 2014; Salloum, Bjoerke, & Johnco, 2019) where grief prevents students from functioning in daily life. Furthermore, students have suggested increasing sensitivity on college campuses for grieving students (Cupit et al., 2016).

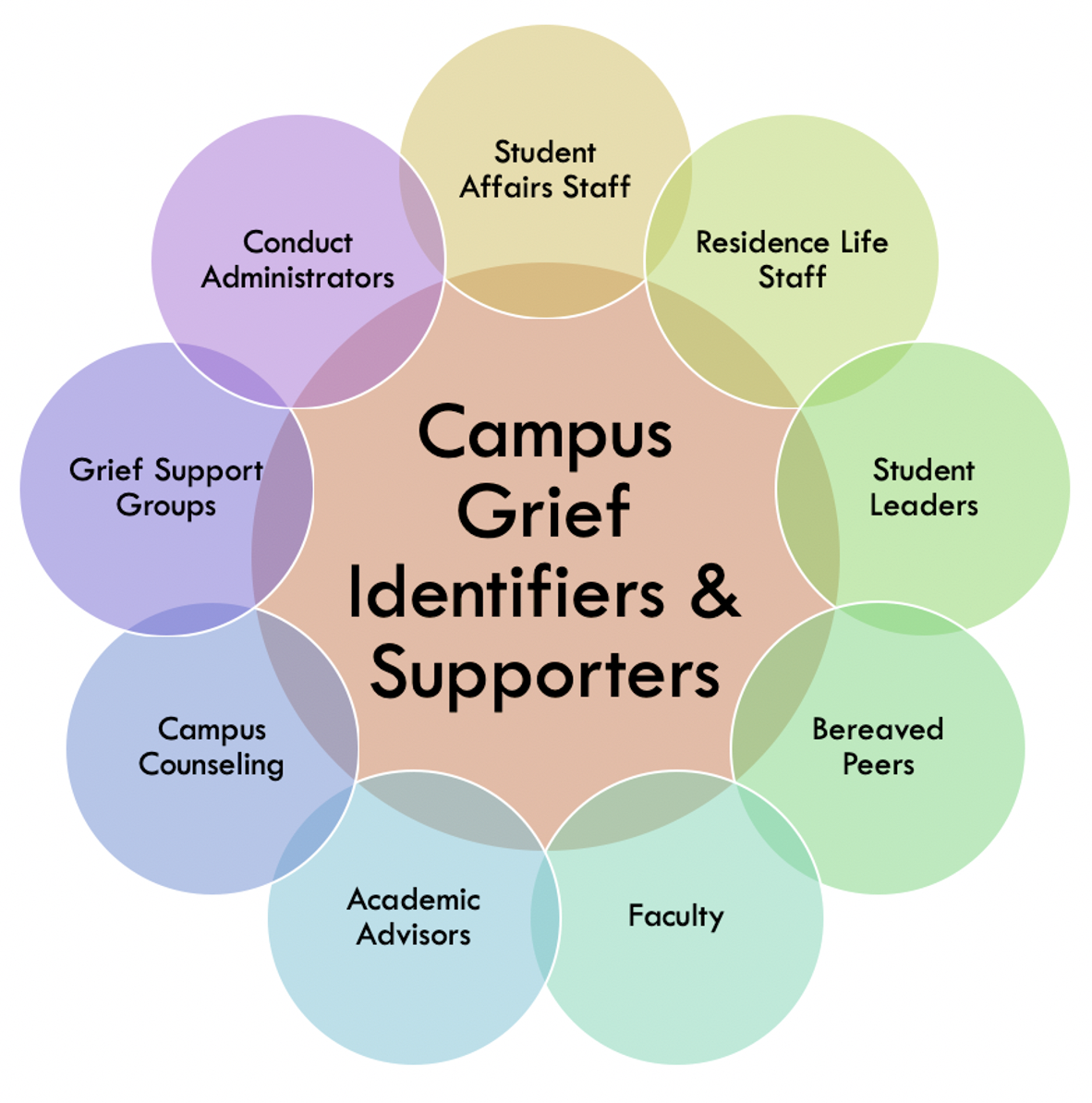

Students do not always need an abundance of support while grieving. Students have previously reported support from peers, especially other bereaved peers, instead of counseling or other supports (Balk, 2008; Servaty-Seib & Taub, 2010). Research has also shown that graduate students are more likely to seek grief support from an advisor, faculty member, or professional counselor (Varga, 2015). These preferences, combined with the fact that campus counseling centers are overwhelmed and understaffed, call for universities to identify and outline appropriate and welcomed grief supports for students.

College campuses are already dedicated to helping students in holistic ways that complement the Holistic Impact of Bereavement (Balk, 2011) and align with the ACPA/NASPA Professional Competencies (2015); however, student affairs staff and faculty members could benefit from bereaved student training (Servaty-Seib & Taub, 2008). Faculty, academic advisors, and academic support programs can be trained to become aware of cognitive effects related to grief (e.g., decreasing grades, difficulty concentrating, inability to complete assignments) and patterns that may signal mental health or other concerns, as also outlined by the Advising and Support Competency (ACPA/NASPA, 2015). Conduct administrators are positioned in a way to potentially uncover activity related to behavioral grief effects, such as drinking or drug use. Student affairs staff and student leaders, such as resident assistants, can identify students whose peer and social interactions change, possibly due to interpersonal grief effects. Campus counseling and health centers can identify grief effects in students and monitor persistent grief behaviors and recommend clinical support as needed for coping. Finally, campuses can create online supports for students. Students utilize social media as helpful grief support (Balk & Varga, 2018; Varga, 2015; Varga & Varga, 2019) and probably do so more now, given the pandemic situation. Figure 3 outlines potential campus entities optimal for identifying student grief effects and providing grief support.

Figure 3. Campus Grief Identifiers and Supporters

Coping with Holistic Effects

Effectively coping with grief and trauma is important to the trajectory of these experiences. When I interviewed 45 grieving college students, preliminary analysis shows themes consistent with the six dimensions of holistic grief effects and positive and negative coping mechanisms. Also, students expressed a need to share their grieving experiences and a desire to help other grieving students (Varga, 2019). One student shared, “I didn’t realize how badly I needed to talk about my grief until I saw your survey come across my email. I opened it immediately when I saw the title of your study!” Another student said, “I’ve just wanted someone to listen to me for so long, and here you are. Someone I can talk to about it – and it’s okay to talk about it. I know you want to listen.” Simply being able to talk about their grief was a reoccurring theme throughout the interviews; however, as one student mentioned, “This isn’t really something you talk about on campus with your friends. You’re just trying to fit in and live the college life. Not bring everyone down.” Some students mentioned campus grief support groups, as well as social media groups, as helpful in expressing emotions and other grief effects related to their loss.

Although this paper’s focus is geared towards college students, these principles and practices can be applied to anyone on a college campus or beyond, including staff, faculty, or other administrators impacted by the pandemic. As outlined in the Personal and Professional Competencies in the Professional Competencies for Student Affairs Educators (2015), it is important that student affairs practitioners continuously monitor positive and negative impacts on their wellness. As seen with the six dimensions of holistic grief effects, we all react to situations differently. You might be thinking about some of these effects you have experienced yourself or in others during this pandemic. What effects have you noticed in yourself, students, or others? How have you addressed these effects? What else can our campuses do to create a safe place for students and the larger community who struggle with effects and need support? What about when students go home? Luckily, families serve as the primary support for grieving students (Balk & Varga, 2018); however, I often have people ask me what they can do to survive these times. To help make it easier, we can encourage students and others to:

-

-

- Understand the various ways people can react to and cope with the pandemic experience using the six dimensions of holistic grief effects as a framework.

- Treat each other with more kindness during this stressful time, especially if we suspect someone is struggling more so with the situation and not with us as individuals.

- Focus on things we can control, which can make change and uncertainty less intense.

- Provide space for each other. It can be difficult for people to process their thoughts or emotions without uninterrupted energy to do so.

- Accept that we do not know what tomorrow will bring. This can be crucial for coping during these unprecedented times. The ability to accept the unknown is powerful. Difficult yet powerful. Acceptance can prompt calmness and provide peacefulness during the chaos.

- Look at the good that is happening. Our communities are coming together in amazing ways, and colleges and universities are continuously dedicated to supporting and developing students.

-

Campuses are striving to provide safe spaces during the pandemic for students, faculty, and staff to live, work, and thrive. We are all trying to figure out how to handle these unique times, feeling various effects, and reacting differently. For those struggling with the stress of this pandemic and everything that comes with it, please know you are not alone. The year 2020 has reminded us of the importance of togetherness. Even though we may feel alone right now, we will get through this together.

Biography

Mary Alice Varga, Ph.D. is an associate professor of educational research in the Department of Leadership, Research, and School Improvement in the College of Education at the University of West Georgia. She is also the Director of the School Improvement Doctoral Program. Dr. Varga teaches graduate-level courses on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodology; program evaluation; and school and classroom assessment. Her primary research focuses on student grief and bereavement. Dr. Varga is a member of the Southern Association for College Student Affairs and the Association for Death Education and Counseling. She is also an Associate Editor for the College Student Affairs Journal and serves on the Editorial Board for Illness, Crisis, and Loss.

References

ACPA—College Educators International & NASPA—Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education (ACPA/NASPA). (2015). Professional competency areas for student affairs practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.naspa.org/images/uploads/main/ACPA_NASPA_Professional_Competencies_FINAL.pdf

Balk, D. E. (1997). Death, bereavement, and college students: A descriptive analysis. Mortality, 2(3), 207-220.

Balk, D. E. (2011). Helping the bereaved college student. New York, NY Springer Publishing Company.

Balk, D. E., Tyson-Rawson, K., & Colletti-Wetzel, J. (1993). Social support as an intervention with bereaved college students. Death Studies, 17(5), 427-450. doi10.1080/07481189308253387

Balk, D. E. & Varga, M. A. (2018). Attachment bonds and social media in the lives of bereaved college students. In D. Klass & E. Steffen (Eds.), Continuing Bonds (2nd ed., pp. 303-316) New York, NY: Routledge.

Balk, D. E. & Vesta, L. C. (1998). Psychological development during four years of bereavement A longitudinal case study. Death Studies, 22, 23-41.

Beam, M. R., Servaty-Seib, H. L., & Mathews, L. (2004). Parental loss and eating-related cognitions and behaviors in college-age women. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 9, 247-255. doi 10.1080/15325020490458336

Cupit, I. N., Servaty-Seib, H., Parikh, S. T., Walker, A. C., & Martin, R. (2017). College and the grieving student: A mixed-methods analysis. Death Studies, 40(8), 494-506. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2016.1181687

Hardison, H. G., Neimeyer, R. A., & Lichstein, K. L. (2005). Insomnia and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved college students. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 3(2), 99-111.

LaGrand, L. E. (1981). Loss reactions of college students: A descriptive analysis. Death Education, 5(3), 235-248. doi: 10.1177/0011000010366485

LaGrand, L. E. (1985). College student loss and response. New Directions for Student Services, 31, 15-28.

Mash, H. B. H., Fullerton, C. S., Shear, M. K., & Ursano, R. J. (2014). Complicated grief and depression in young adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(7), 1-5.

Mathews, L. L., & Servaty-Seib, H. L. (2007). Hardiness and grief in a sample of bereaved college students. Death Studies, 31, 183-204.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 519-543.

Parikh, S. J. T., & Servaty-Seib, H. L. (2013). College students’ beliefs about supporting a grieving peer. Death Studies, 37, 653-669. doi:10.1080/07481187.2012.684834

Pollard, B. L., Varga, M. A., Wheat, L. S., McClam, T., & Balentyne, P. (2017). Characteristics of graduate counseling student grief experiences. Illness, Crisis, and Loss. Available online at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1054137317730525

Salloum, A., Bjoerke, A., & Johnco, C. (2019). The associations of complicated grief, depression, posttraumatic growth, and hope among bereaved youth. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying, 79(2), 157-173. doi: 10.1177/0030222817719805

Schwartzberg, S. S. & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1991). Grief and the search for meaning: Exploring the assumptive worlds of bereaved college students. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 10(3), 270-288.

Servaty-Seib, H. L., & Hamilton, L. A. (2006). Educational performance and persistence of bereaved college students. Educational performance and persistence of bereaved college students. Journal of College Student Development, 47(2), 225-234.

Servaty-Seib, H. L. & Taub, D. J. (2008). Training faculty members and resident assistants to respond to bereaved students. New Directions for Student Services, 121, 51-62. doi: 10.1002/ss.266

Servaty-Seib, H. L., & Taub, D. J. (2010). Bereavement and college students: The role of counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(7), 947-975.

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9).

Taubman-Ben-Ari, O. (2004). Intimacy and risky sexual behavior – what does it have to do with death? Death Studies, 28(9), 865-887. doi: 10.1080/07481180490490988

Varga, M. A. (2015). A quantitative study of graduate student grief experiences. Illness, Crisis, & Loss. doi: 10.1177/1054137315589700

Varga, M. A. (2019). Reflections on grief research interview participation. Death Studies. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2019.1648334

Varga, M. A., Bordere, T. C., & Varga, M. D. (2020). The holistic grief effects of bereaved Black female college students. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying.

Varga, M. A., & Varga, M. D. (2019). Grieving college students use of social media. Illness, Crisis, and Loss. doi: 10.1177/1054137319827426.

Vickio, C. J., Cavanaugh, J. C., & Attig, T. W. (1990). Perceptions of grief among university students. Death Studies, 14(3), 231-240. doi 10.1080/07481189008252364

Walker, A. C., Hathcoat, J. D., & Noppe, I. C. (2012). College student bereavement experience in a Christian university. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying, 64(3), 241-259. doi 10.2190/OM.64.3.d